Reviewed by Rachel Loring

Reviewed by Rachel Loring

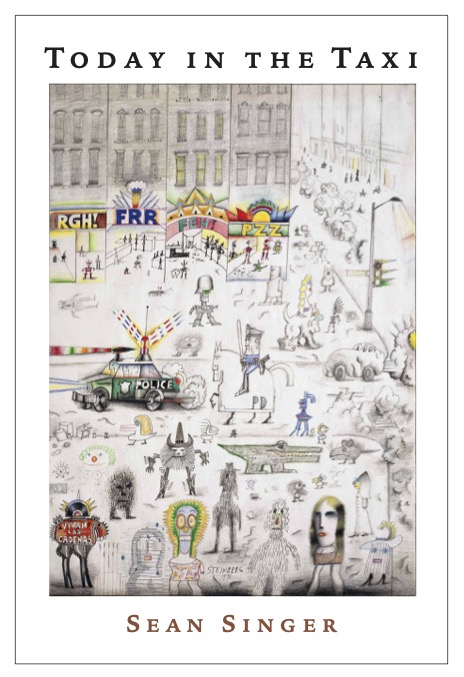

Today in the Taxi

by Sean Singer

Tupelo Press

April 2022, ISBN: 978-1-946482-69-3, Paperback

Sean Singer’s taxi cab glides through New York City. Its passengers? Famous celebrities, wall street bros, jazz musicians, fighting couples, possibly negligent mothers, and most important of all, the driver: a poet on his own journey, consumed by thought and desperate for reassurance and connection.

Today in the Taxi is deceptively plain, its language is conversational and the voice used to describe its absurd situations is unembellished, often just describing things for what they are with concrete imagery. But underneath the unconcerned, detachedness of the narrator’s descriptions are deep ruminations on one’s own life, city, the lives of others, and how it all blends together.

Moments of simple, yet thoughtful revelation are buried throughout the text. In “Schism”, the narrator drives a crying woman and ends the poem with the idea that, “..she’s really saying: You are / worthy of asking and having your question heard.” It’s small moments like this, sandwiched between mundane taxi trips where Singer allows his poems to become greater, compelling narratives.

Like all great pieces of literature, Today in the Taxi is in continuous conversation with other work, which it does through its near constant stream of quotes and references. While most of these come in the form of in-text quotes, other references are in poem’s titles or in the nods to various people and stories Singer weaves into his work.

Oftentimes these excerpts act as answers for the narrator’s own questions, which Singer uses to paint a character defined by their commitment to inner worlds of reference. Singer creates mythos from the people he quotes, like in the case of Duke Ellington and Kafka, while simultaneously harkening back to actual mythos, like the Golem of Prague and religious texts.

It can not be understated the sheer volume and variety of quotes and lifted text used in this collection. Singer uses the words of philosophers, authors, musicians, unnamed comedians, and even a part of a Cathar fragment. However, these quotes are worked in with ease, never coming off as bloated or worse, pretentious, but as an organic part of the narrator’s stream of thought. There is a believability in these interactions. Like the backseat of a cab, there is a lived-in quality to the quotes used, a sort of intimate knowledge the narrator has of them.

Signer’s quotes are not just quoting for the aesthetic of intertextuality, but quoting as an act of self realization; when the narrator reflects on his thoughts about being a writer after an encounter with celebrity Carey Mulligan, he turns to Kafka; when he drives around a drunken man, he thinks of Charles Mingus; when he drives through all of New Jersey in ten hours and doesn’t get a single tip, he thinks of the routine from an anonymous comedian. Singer’s references work to add richness and texture in his poems. They say what the narrator is too self-conscious, or too self-aware to say. The gaps between Singer and his references are poetic shifts that border on epiphany. The reader is put into the mind of the narrator, a character who relies on words as a comfort, or even maybe more accurately, as a way of making sense of the absurdity and painful transitory ambiguity of life.

The narrator’s most frequent conversation partner is Kafka, a reference that pulls a double shift in the work as many of the narrator’s qualities and problems are Kafkaesque. Today in the Taxi’s focus on an individual worker as they struggle through circular reasoning and the clinical realities of their job emulates some of the absurd, frustrated nature of Kafka. We see the narrator default into driver mode throughout the poem, usually in moments of great intimacy or as a way to pull back outward. The trappings of the narrator’s job seem to keep them in a constant state of rumination, something Singer likens to “both stationary and moving, looking forward and responding back.”

The juxtaposition of looking forward and responding back are the crux of the narrator. There is a continuous sense of contrast throughout the work. There is contrast in the form and structure of the poems: almost every poem starts with the words “Today in the taxi” which should imply a sameness, however each repeated opening line is contrasted with a completely unique trip being decribed. There is also contrast in the substance of the poems. Like how the inner world of the narrator moves forward in the taxi, but they always are thinking back to the work of others or how the narrator is driving people around all day, while spinning the wheels of their mind.

Singer masterfully and subtly explores many of these dualities that seem in conflict with each other: the driver and the writer, the apprentice and the idol, the mundane and the divine. These contrasts provide a sense of conflict throughout the poems. A war between identities and narratives. There is conflict between the narrator’s life and their thoughts, conflict between the pasanger and the driver, and conflict between the tipped and the tippers (or, more often, the non-tippers).

The burgeoning crises in these conflicts come to a head in the poem “Road”, which feels distinctly solemn. It is a quiet, noiseless glimpse into the narrator without passengers and excerpts to distract us. If the poems are a ride through New Yorks’ bustling streets and glowing night lights, this poem is a driver parked. This is a driver at a red light, alone, with the radio off. The simplicity of the narrator’s thoughts, the ambiguity (the fiction writer’s dreaded “thing”) works here with its frankness. We are presented a thing, we are presented the narrator’s faults, and we listen, as they don’t ask for help from Kafka or Ellington, but as they sit with the idea that their life should have been different in some amorphous, heartbreaking way.

In “E Minor Sonata”, Singer quotes Simone Weil, “Attention is the rarest / and purest form of generosity”. Today in the Taxi is an exercise in attention. Our narrator thinks himself an ultimate witness, and what is the act of witnessing if not giving up one’s attention. Is our narrator’s witness to the small intimacies in his cab an act of generosity? Is his continued reverence and witness to the work of others some ultimate kindness? This is what the collection is speaking on: the attention we pay to others, those who drive us and those who we drive, the attention we pay to stop signs and street names, the attention we pay to our own thoughts, the attention we desperately wish we could have or not have, and the attention we give our fears, our short comings, our desperate desires. So it is with generosity that Sean Singer looks at us in his review mirror, shifts the gear into drive, and asks us where we are headed.