Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

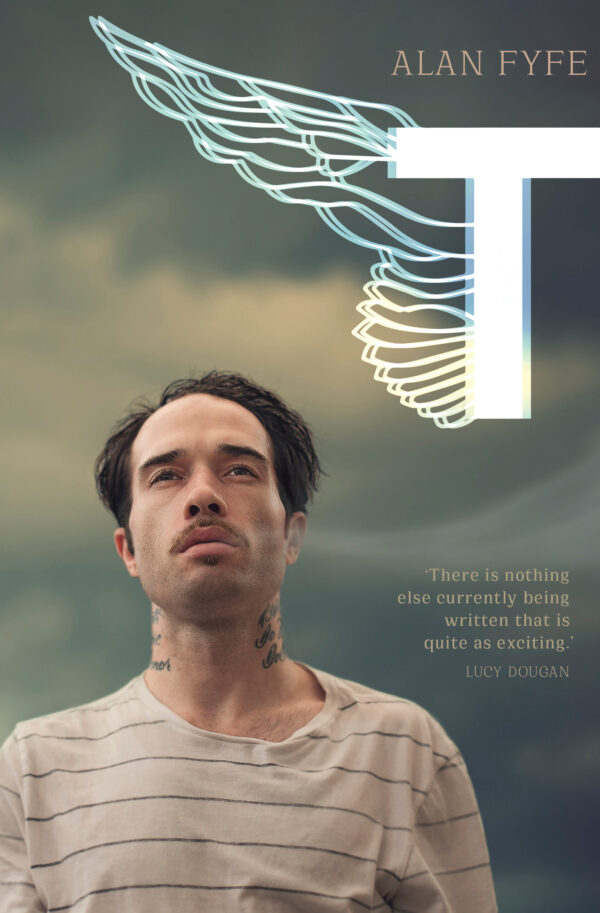

T

By Alan Fyfe

Transit Lounge

ISBN: 978-0-648414-03-2, Trade Paperback, 232pp, Sept 2022

T is the sparse nickname of Timothy Ami, a homeless, down-on-his-luck meth addict and dealer in Western Australia’s Mandurah suburbs. T tries and fails to give up his addiction, stop dealing, and to be some kind of partner to Lori-Bird, the woman he loves. Fyfe does a terrific job in capturing both the seductive pull of T’s need and his rapid decline and things begin to disintegrate. Told in third person narrative, with T’s point of view, the story follows T’s various attempts to score, sell, find a place to live, and in some odd way, to find meaning. To say that T’s world is grungy would be an understatement, but Fyfe’s writing is consistently rich and poetic:

T woke up at noon with sand in his mouth. He spat it out and saw blood mixed in with the grains and frothy phlegm. Then came the familiar choke, searching for plain breath. It was a grating cough that made his head buzz – a little phase-out and recall of the toxic smoke he’d run through his lungs. Between fits, he drew long breaths to try and force a satisfying amount of oxygen back in. Satisfaction was nowhere in the neighbourhood, so he fell onto the sand and rode out the spasms until they passed. (23)

The book is immersed in place. So prominently does the city of Mandurah feature that it almost becomes a character. Layers of trauma beneath the dirt filter into the modern day places from the salt flats, Yunderup road, or the shopping mall store “Kingdom of Mist” where T buys a glass pipe. There are many individual traumas that mirror T’s including a fourteen year old boy he ends up giving a hit to, or the ongoing desolation as T and Lori-Bird visit the otherwise homeless families she’s helped house for cheap rent in asbestos-ridden, abandoned shacks. All of these “nobody people” are part of a pyramid of oppression that profits someone further up. The link between T’s world and the colonial trauma that underpins the Peel Region place is beautifully managed through alternating passages that provide an historic context to the present day Mandurah, zeroing in on Thomas Peel, after whom the region is named:

From a distance Peel might have looked like a better human than an oversized redhead who drove a moving truck, for the fact that he had a whole massive region named after him. (83)

Although Peel’s story is presented separately to T’s, the incompetence and brutality that culminates with the Pinjarra Masacre forms a connection between the terrible impact of colonialisation and the modern day social issues like unemployment, drug abuse and homelessness that form T’s world. This link becomes particularly clear when T meets up with one of his customers in a car park: “It was here, Peel and Stirling killed those Binjareb right here.” (164) This connection creates a circularity that belies the desolation of T’s existence, showing its deep-rooted origins and a way out that hints at recognition and reckoning.

The characters in the novel are well depicted and believable – with just the right blend of hopelessness and quirky creativity. T’s feelings for Lori-Bird, and his innate creativity make for a character who is charming in spite of his hopelessness:

In this way, Lori-Bird’s room became the main reference point for T’s erratic orbit, and she became the gravity at its centre. On any given summer day, her eyes would close against the angry light, her fingers touching her cheek where a patch of sun fell. Maybe she’d tell him a. Secret, maybe engage him to burst out with his own, or maybe she’d utter a simple phrase that told him his life was running with her calm consent. (83)

There are many ghosts that populate the book. Some are overt, like the “poet, muso, shard-monger, late-night theologian” busker Gulp, whose semi-comical death opens the book. T slowly begins to inhabit Gulp’s world – from his house to his role as drug dealer, in spite of the cryptic warnings that Gulp’s ghost conveys. Other ghosts include the Binjareb people massacred at Pinjarra – an unsettled score and point of rupture the reverberates through the book, exacerbated by Peel’s name being used for so many of the spaces in this story. There is the ghost of T’s mother, who died when she was hit by a speeding car when T was nine years old. That he ended up collapsed in a graveyard next to Peel’s headstone before taking on the somewhat homeless state he has remained in further links T’s pain to the ongoing impact of Peel’s brutality. There are also the ghosts of other people who die throughout the book, including a man who seems to fall from the sky in front of T. These deaths take on a magical quality, weaving through T’s drug-induced hallucinations with a great deal of humour.

Many of the characters are Dickensian, such as the dangerous drug supplier Cardo, who makes T sing for his drugs, and who one day holds a Satan infused “seance attempt to call forth Gulp: “Great Baphomet, so mote it be!” Which ends when his Shetland pony called Lord Jinglemuffin walks into the room. There is Sean Elgin, who is able to levitate and whose farm forms another kind of respite. These moments of quiet zany humour work perfectly, without undermining the seriousness of the book, or swerving from T’s trajectory. Though T may read like a dark and disturbing novel, there is something inexplicably uplifting about it. Perhaps it’s because the book forms its own kind reckoning–the small moments of joy that T finds, even in his most bleak moments, or the way creativity and the connective tissue that binds us together somehow breaks through.