Reviewed by Cathy Ferrell

Reviewed by Cathy Ferrell

We Are Changed to Deer at the Broken Place

by Kelly Weber

Tupelo Press

ISBN: 978-1-946482-80-8, Paperback, Dec 2022, $21.95

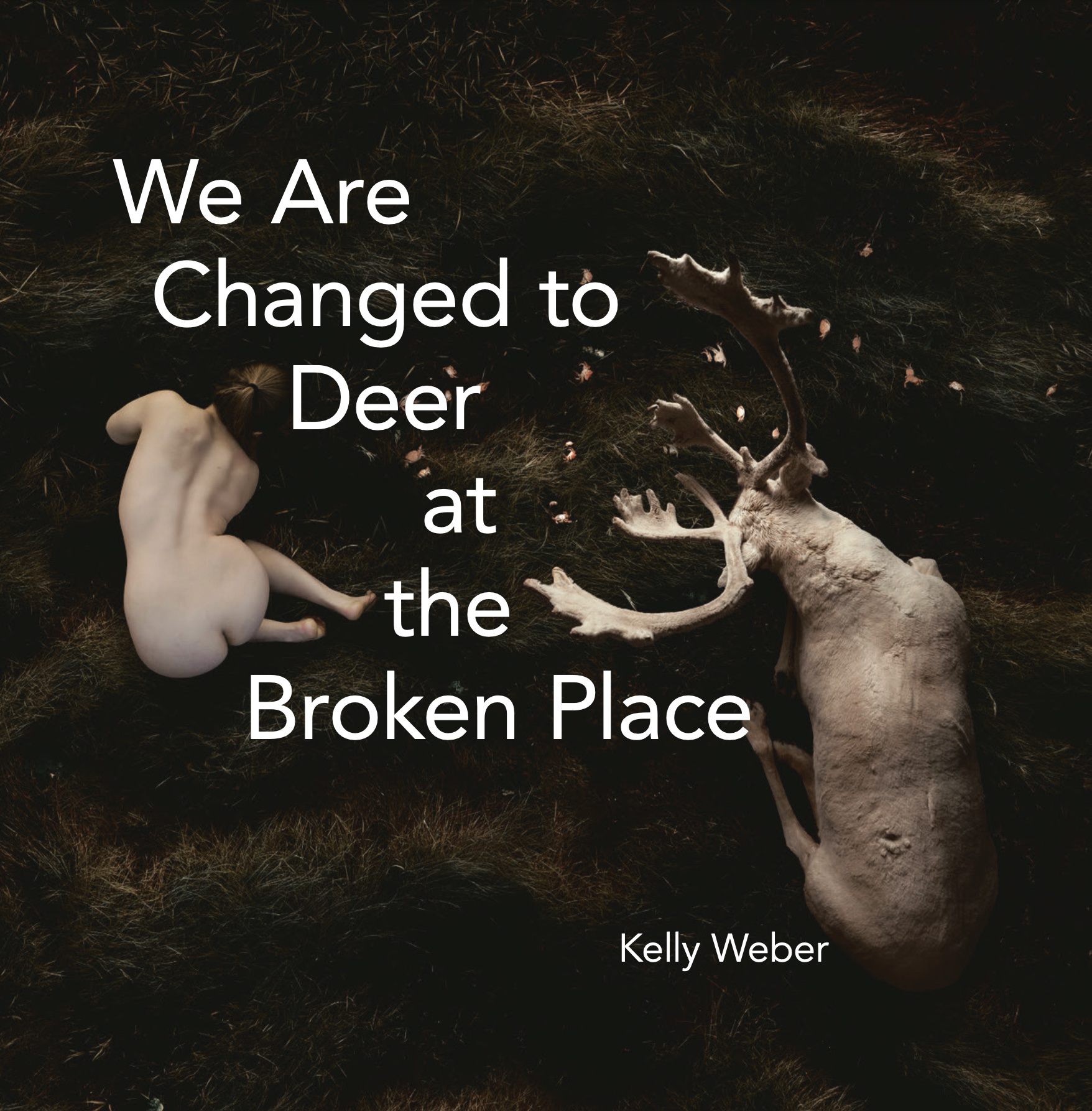

I am a curious human. I had questions before I even opened Kelly Weber’s debut collection. On reading the title, I wondered many things. What does it mean to be broken? Who is doing the breaking? Why the deer? I wondered about the woman in the cover photograph, her soft curves curled into a yin-yang-like swirl around the deer’s pronged antlers. What is left after the breaking? In their collection of lyrically crisp, crackling poems, Kelly Weber explores the nuances of otherness, the things that can be broken, and what happens after.

To me, We Are Changed reads less like a narrative and more like a conversation. The poems live and breathe as they hearken back to themes spread across the breadth (and breath) of the book. Weber begins with a sort of nocturne. In “What the Water Bruises Into,” we muse and return to places of memory and of trauma with the poet, places where she has been told who to be: “…give her the term she is before she knows…” It is interesting that Weber, who uses she/they pronouns, chooses “her” in this line. Subtle choices like this one are embedded throughout the work. Weber explores the myths of female identity in a rush of language. There are punctuation marks, but no period to mark the ends of sentences. By the end of the poem the poet has breathlessly taken the concept of identity into their own hands, their own voice, rebirthing and rediscovering themself. In one of the opening lines, sex ed students are warned what to do “if a girl says no…” Weber’s answer to the self is an exultant “yes, yes, yes.”

Section I presents a dangerous world, one that seeks to hunt, conquer, possess. In “Abstinence,” Weber wears the mask of cultural expectations as a way to remain unseen. “I am one of the good girls,” she insists. However, we see on the page the beginnings of a break with tradition and norms. The lines do not start on the left-hand side of the page, as expected, or follow neatly one after the other in couplets or stanzas. Reading them, you’ll find your head nodding back and forth, shaking no. Looking at the shape of the text on the page, the beginnings of the right-aligned text merge with the middles of the left-aligned text, creating a line down the page of poetry, like a spine. And then, we read these words: “People think it’s a cross / but it’s my spine I’ve tacked above the bed.” Has she sacrificed identity to satisfy the outward eye? Surprises like these challenged me as a reader, in the most intriguing way. Weber also uses sound to suggest the push and pull between outward expectations and inner self. The mix of sharp and soft sounds, particularly /c/ and /s/, and the hard stop of /d/ are examples. There is a self she allows others to see and the “I” (another sound echoed throughout the line) that is cracking open underneath.

Weber cracks open their “good girl” facade to reveal something Other. Section II is an exploration of the aroace world as she experiences it, and the stripping away of the outer. Weber begins with “Nocturne With Aroace Girl.” The poem poses a question: “What pulls a person like me / out here alone, they want to know?” A person like me—what does that look like? And why is it strange to be alone? There is more push and pull here, but this time the aroace girl is steering. Words such as steer, winding, road, drive, highway, wheel glitter, headlights point to a journey, while vertebrae, backbone, throat, thirst, larynx, breath, cervix root us in the body. Then Weber surprises us with images of defiant birth and explosion. “Dilate shale’s radio song. / Strip sorrow from the larynx. Not broken / but igneous.” These are compelling images; she pushes forward a fiery newborn self.

Continue reading, and you’ll find more surprises. Weber plays with form, breaks it, reshapes it. “Aroace Girl : Plainsong Elegy” looks like two simple columns scrolling down the page, however they take on different lives when read in different directions. Read the stanza vertically, and you get “this is how I find you huddled, fast boneset and / rocking against wall with your tongue / ringing winter air…” Read the same opening line horizontally from left all the way to the right, and you have a pause, a break, in the middle. “this is how I find you huddled, false boneset and” [breathe here in the pause] “antelope horn clenched in your fist…” The breath gives us a bridge between the contrast of a strange cowering creature and a defiant fist clutching a symbol of virility. She cracks the image in two.

The Omphalos poems of Section VI spoke the most to me, as a reader, and to each other, as living entities made up of words that breathe and pulse. Omphalos means center or hub; although the poems occur toward the end of the book, they are like a heartbeat tying it all together. Weber reflects on their own birth in “Omphalos: Termed.” I appreciated the play on different meanings of the word: full term as in gestation, gender terms, terms of endearment, terms and conditions, a specific name. “This is how you be a person / the world will call a woman,” their mother teaches them. This, from a mother who “learned to mother / from a mother who wished her a boy,” as we see in “Omphalos: Shorn.” The myths and patterns of mother-daughter relationships bleed over into each other through birth, expectations, and the lines on these pages. Weber reverses the roles at times, seeking to hide their own mother within themself. The closing lines of “Shorn” are sharp and beautiful: “I heard the clock unwind / its teeth, its pendulum the ungrown pulse / of night and all its tongues–broken / surfaces, what we labor forth to light.” (It is interesting to note that the Spanish term for giving birth is dar a luz–to give to light.) Section IV bleeds with birth imagery, broken bones, and destructive generational patterns. “Omphalos: Gnostic” hearkens back to “Sinkbox” as the speaker holds their breath “in a frozen grove” just as their grandmother did underwater. She must unlearn all the old myths or expectations such as “telling myself to be quiet” just as she did in “Omphalos: Chrysopoeia” and “Abstinence” (from Section I). The conversations happen quickly, deftly; keeping pace was an exhilarating challenge.

My copy of this book is filled with quickly scratched notes, annotation symbols only I understand, question marks, small open hearts, underlined sentences, circled words, messy smudges, angry creases. I struggled. I read and re-read. I wondered. I questioned. I chased. I stretched. At times I thought I might break, as well. Many things can be broken: bones, relationships, spirits, bodies, homes. Brokenness can kill or it can reveal something new. Hunters kill fauna, the patriarchy oppresses, children break out of the womb, society breaks those who break rules. But maybe it is not always a bad thing to be broken. After all, gems don’t reveal themselves until their rough outer shell is cracked open. Kelly Weber breaks bonds. The woman on the cover becomes the deer—genderless spirit, content and complete in itself, darting swiftly through light and shadow alike.

About the reviewer: Cathy Ferrell is a poet, writer, and educator from Central Florida. She attended Florida International University, and currently serves as a Reading Interventionist in virtual high school classrooms. She finds inspiration in her morning walks, hybridity (in language, culture, or anything), and generational memory. Her work can be found online at sinkholemag.com and in the scholarly collection, Shakespeare and Latinidad, edited by Trevor Boffone and Carla Della Gotta. She is an alumna of Tupelo Press’ 30/30 Project, October 2022 cohort.