Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

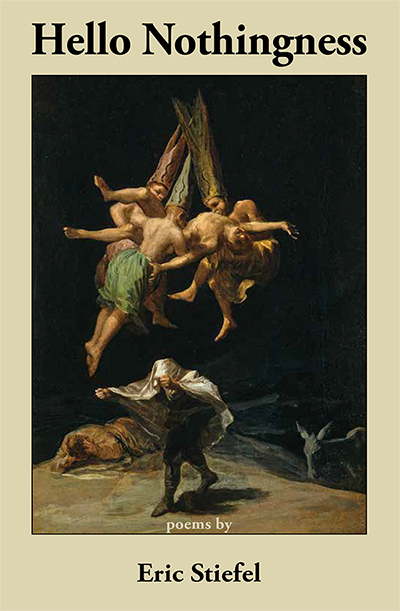

Hello Nothingness

by Eric Stiefel

Main Street Rag Publishing Company

Nov 2022, $14.00, 66 pages, ISBN: 978-1-59948-942-2

The title of Eric Stiefel’s new collection comes from a poem called “The Next Painting Was Full of Dark Clouds,” which ends: “Hello, nothingness, I start to say. Hello, hello.” The poem is “after Goya,” we learn from the epigraph, specifically, Goya’s paintings, The Dog and The Parasol, as Stiefel tells us in his Notes. The first is rather bleak, one of Goya’s Black Paintings, showing the animal gazing forlornly upwards in a foggy atmosphere, apparently in distress. The Parasol, on the other hand, shows a serene scene of everyday bourgeois life, a young man shading a young woman with the title umbrella. The contradictory images reflect themes throughout Stiefel’s verse, which oscillates between nihilism and contentment – or at least resignation and a sensual appreciation of the ephemera of the world. As he writes in the opening poem, “Lest”: “I devour everything I can, the mind defaced, a tattered gown, strawberry leaf, a statue, half-submerged.” Nothing is beneath notice. Hello, Everything!

But Stiefel does strike a cynical, dispirited tone right away. The first section, “A Pitying of Doves,” begins with the poem, “I’d Gone Missing and Wondered What the Implications Were”:

I’d gone missing from myself, is what I meant to say.

Or meant to believe. Before I got distracted thinking

how different everything looks when it’s covered in snow.

Distracted is the key word. Sidetracked, abstracted, confused, perplexed. In “Tell Me Who I Am” Stiefel writes, “ I don’t know / who I am, not just the story of who I am,” and the poem concludes on the despairing note: “How do we hold ourselves against the abyss?” The very title of “The Clock Ticks Toward Ruin” echoes this despair. The speaker is collaborating on a one-act play with a woman named Rose. “I know some part of me has to die / each time I start another day,” the speaker laments.

A voice, speaking “into the deepening hollow divide / between what’s real and what one says is real,” asks, is this all there is? It’s sneering, sarcastic, world-weary, making one think of the Jerry Lieber-Mike Stoller song Peggy Lee made famous, “Is That All There Is?” But in the very next poem, “Aubade,” Stiefel reminds us “that the palpable remains palpable even when it’s gone.”

Many of the poems are addressed to “you.” Sometimes that is another person, a former lover, the reader intuits, but sometimes he is talking to himself, “Sketch on a Hotel Napkin” begins: “I was stuck inside the second person / and didn’t have time for anyone.” “Where are you going?” the poem concludes, echoing the uncertainty and disorientation of “I’d Gone Missing and Wondered What the Implications Were.” “You brace yourself

against the coming tide of here and then.

As if anyone could ever know.

But a handful of the early poems address a “you” who seems to be a former lover. “Always a Game of You” is a multi-part poem that alludes to Eliot’s “The Waste Land” in which the speaker laments a former love, likewise causing confusion. “Wasn’t it the house within the dream, the last time / I saw you?” the speaker asks. “You’re not the same person / every time I picture you in my head.” “Each version of you begins to blur together.” The poem “I Mean for a Thing to Be Other,” likewise addressing the unnamed “you”: “When I think of you, I think of you as you were, lying nude.” “First, I Thought of You” is also saturated with this feeling of regret:

Sometimes my eyes are more clever

than a turntable, like a voice at the top of a stairwell

which says don’t you remember what could have been? As if it were

a teacup still warm on the bedside table, as if memory could

collide back with me as a lone figure approaching from the outline

of a landscape.

A subsequent poem, “Melancholia,” whose title is consistent with the overall mood, is also addressed to this “you.”

The overall theme of chaos continues with reference to Alan Turing in “Each Object Seems to Appear on the Same Flat Surface” and in “Phenomenology,” a poem taking its name from the philosophical school that focuses on consciousness and its objects, which I’ve always thought verges into solipsism. “The wolf on the road to nowhere.”

Stiefel writes in the poem, “Garden of Earthly Delights,” which takes its name from a painting by Hieronymus Bosch, “Chaos fascinates me—I’ve fallen / in love with any number of uncertainty principles.” This poem comes from the second section whose provocative title is: “Are You Willing to Submit to Your Sanity to Become Fully Human?”

Stiefel finds inspiration in a number of paintings throughout this collection, not just Bosch. “Encountering Judith and Holofernes” refers to Gustav Klimt’s Head of Holofernes. “Strained, as the Day Turns” is after Edvard Munch’s Love and Pain. “By the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate,” an homage to Mary Jo Bang, also contains references to Klimt and Munch, as well as to Salvador Dali. And of course, as noted earlier, Francisco Goya is an inspiration.

While the title, Hello Nothingness, is mischievous, even frisky, the book is a stark, honest statement, at once lyrical and profound.

About the reviewer: Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore and Reviews Editor for The Adirondack Review. His latest book, Catastroika, was published in May 2020. A chapbook of poems, Jack Tar’s Lady Parts, is available from Main Street Rag Publishing. Another poetry chapbook, Me and Sal Paradise, was recently published by FutureCycle Press. An e-chapbook has also recently been published online Time Is on My Side (yes it is). Another chapbook, Mortal Coil, is forthcoming from Clare Songbirds Publishing.