Reviewed by Ruth Latta

Reviewed by Ruth Latta

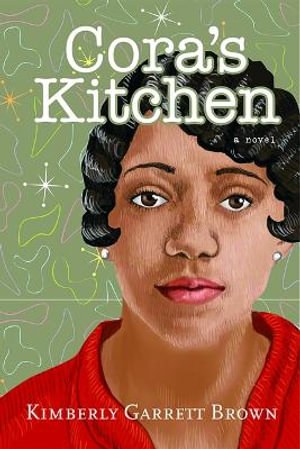

Cora’s Kitchen

by Kimberly Garrett Brown

Inanna Publications

ISBN: 9781771338516, Paperback, 280 pages, 15th Feb 2022

Cora’s Kitchen is about a woman’s dream deferred. Author Kimberly Garret Brown, the founder of Minerva Press, begins the novel with a quote from “Troubled Woman” by Langston Hughes, which describes a woman, “bowed by weariness and pain/like an autumn flower in the frozen rain.”

This poem strikes a chord with Cora James, a librarian, wife and mother living in Harlem, New York City, in 1928, during a golden age of African American culture. Lasting roughly from the 1910s through the mid-1930s, the Harlem Renaissance period pulsated with Black American literature, music, stage performance and art. Langston Hughes was a part of it and Cora wants to be part of it too. Her husband, Earl, is a part of the cultural scene as a musician who comes alive when he performs at a nightclub in the evening.

She and Earl have always tried to advance his aspirations as a musician, while she pretended she had no dream other than her job, her household and their two children. Working in a Harlem library, she met Langston Hughes at the library forums and the booklovers club, so decides to write to him about her ambitions.

“No one talks about poetry, books or writing the way you and I did over the last year,” she says in her letter. Presented in journal entries and letters, Cora’s Kitchen features an engaging, thoughtful narrator/protagonist who is fully-rounded and unique, yet universal in her frustrations as an aspiring writer. To her delight, Langston Hughes replies. Although he is now studying in Pennsylvania, he remembers Cora and is happy to discuss literature with her and to suggest that she enter a short story contest sponsored by Opportunity magazine.

Eventually they discuss whether or not male authors accurately depict women. Langston tells her that Black writers have a responsibility to their community to be “the voice for a people who have been silenced for centuries.” He urges her to “tell the story of the strength and perseverance that courses through your veins. Don’t strive to be a great writer; be a great Black writer.”

Langston, single and supported by a patron, has never worried about his thirteen year old son falling in with a bad crowd, as Cora does. Her sense of duty extends beyond her nuclear family to her cousin, Agnes, who is so badly beaten up by her husband she can’t go to her job as cook at the home of the wealthy Fitzgerald family. Cora, who has never wanted to work in domestic service, takes time off her library job to fill in for Agnes.

This good deed, seems to turn out to Cora’s advantage. As Langston Hughes tells her, she may find time to write there. In Washington, he worked in a laundry sorting dirty clothes, and wrote many poems during that period of his life.

The Fitzgerald family includes the husband, a banker who is often away, his wife and four young boys. Cora usually has an hour of uninterrupted time in the kitchen which she uses to write. When Mrs. Fitzgerald, Eleanor, discovers her writing, she is enthusiastic and supportive. Discussing Agnes’s brutal husband, she says, “I don’t believe that men and women are meant to live together. Whenever Mr. Fitzgerald goes away, I breathe easier and feel freer.” She praises Cora’s short story in progress and lends her a novel, The Awakening by Kate Chopin.

While identifying with Chopin’s protagonist, a woman trapped in a stifling marriage, Cora sees that the character is more like Eleanor than like herself. Langston Hughes has recommended several novels by women of colour, such as those by Jessie Redmon Fauset, and Nella Larsen’s novel Quicksand (1928) which Cora rates as “by far the best book [she’d] ever read written by a coloured woman, or man, for that matter.” Cora’s discussions and thoughts about poetry and fiction are a fascinating element in the novel and will introduce many readers to some notable but neglected authors.

Cora overhears the Fitzgeralds quarrelling about a women’s group Eleanor attends. Mr. Fitzgerald wanted her to join a garden club, or the Daughters of the American Revolution, not a “group of Jezebels.” Later Cora learns that it is a feminist group, and also, that Eleanor’s inherited money provides the family’s comfortable lifestyle. Mr. Fitzgerald controls her trust fund and gives her a monthly allowance.

When Agnes takes her job back, Cora feels sad. “What I experienced in the Fitzgerald’s kitchen showed me there is more to life than trudging through the day,” she writes. Then Eleanor turns up at the library to offer Cora a seemingly wonderful opportunity – to accompany her to the family summer home on Seneca Lake in upstate New York for two months. She will pay Cora a stipend that exceeds her library salary, and will make the library hold Cora’s job for her. At the cottage Cora will have a quiet place to write with no distractions or responsibilities.

It sounds too good to be true, but Langston writes to Cora that he and many other Negro writers have white patrons; otherwise they couldn’t afford to write.

“I understand the hesitation of accepting money too easily from white folks,” he writes. “Far too often they are like Greeks bearing gifts.”

Nevertheless, he urges her to take the risk, so Cora ships her two children off to Georgia for the summer with her Aunt Lucy, makes arrangements for Earl’s meals, and accepts the offer.

Langston Hughes tells Cora that she will have the chance “to observe white American life from the inside without sacrificing who you are,” but it doesn’t turn out that way. Although Cora does not end up like the heroine of The Awakening, she barely survives being Eleanor’s protégé. Nevertheless, she resolves, near the end, to be a writer for women and for African-Americans. “I belong to both equally,” she writes.

Kimberly Garrett Brown has written an outstanding novel which rings true as a depiction of a budding writer and conveys an important message about overlapping, concurrent forms of oppression.

About the reviewer: Ruth Latta’s most recent novel, A Girl Should Be (Ottawa, Canada, Baico, 2021, info@baico.ca) is the maturation story of a Canadian girl coming of age during the Roaring Twenties and Dirty Thirties. Currently she is at work on a novel inspired by the life of a Canadian woman trade unionist.