Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

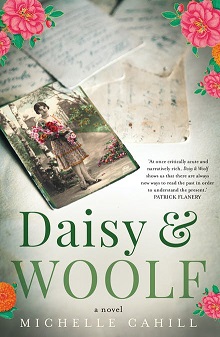

Daisy & Woolf

By Michelle Cahill

Hachette

April 2022, ISBN: 9780733645211, Paperback, $32.99

Writing through a literary icon like Virginia Woolf is no small undertaking. Such a canonical pressure might overwhelm many a novelist, but Michelle Cahill has managed it perfectly. Daisy & Woolf is a rich, complex book that blurs binaries and boundaries, provoking big questions around art, parenting, love, privilege, colonisation, and creativity.The narrative flows quickly, driven by its dual protagonists, with the book unfolding its denser meaning later, in the shared collaborative space between reader and writer:

Writing is like scouring time, sketching patterns from correspondences, a kind of oracle. Cutting velvet, twisting threads, all the things that cannot be deciphered and have no substitute like pieces of shimmering glass. Birth and death rammed into each other. Deep, deep in my grief, I am the broken sky searching for the words as the light falls. (77)

Mina Waters is an Anglo-Indian Australian writer temporarily in London to write the story of Daisy Simmons, a minor character and the love interest of Mrs Dalloway’s Peter Walsh. In Mrs Dalloway, Peter is a somewhat unattractive character, prone to emotional displays, jealous of Daisy’s husband and keen for her to divorce her husband and come to England to marry him, only to lose interest when she arrives. His attitude towards India is patronising and his objectification of Daisy suspect, but Woolf does little to tease these issues out, or the self-aware classism inherent in Clarissa Dalloway’s attitude towards Miss Killman with her old Macintosh and the unemployable Peter who cannot stop playing with his knife. Daisy & Woolf engages deeply with these issues along with the exploitations that are part of the spaces that Mina and Daisy inhabit, though always subtly, always expertly woven into the story:

We in the West are accustomed to brushing off our complicity and our guilt at the crimes of poverty, injustice, exploitation. Nothing much on paper, nothing in the history books, the official records, just the smoke of words, the daily crossings of pedestrians through parks, the vomit-stained paving stones of the Royal Borough. (141)

Cahill handles Mrs Dalloway beautifully, engaging openly with its issues while also paying homage to Woolf’s writing skills, utilising multiple layers of stories of colonisation both at the height of the British Empire in India and its legacy post-empire. Lucrezia is another minor non-English Woolf character who comes alive in Daisy & Woolf, her marginalisation pivoting as she returns to Italy and changes the course of Daisy’s life.

Mina’s own story is engaging as she works to manage her dwindling grant money and the necessity of jugging ongoing paid work in academia with her difficult novel, a needy child back home, grief at her mother’s recent death, and her own sexual desires against a forbidding canon. Mina’s work takes her to and from Australia and London, New York, India and China, with Mina’s travels and personal struggles mirroring those of Daisy’s.

Daisy’s story is written primarily in epistolary, letters drawing the reader in as confidante to her insecurities, her growing sense of self, and her relationships. There is a direct connection between Daisy’s world in 1924 and Mina’s in 2017 that dissolves the time gap since both are happening in the same present, an entanglement which Cahill handles with poetic grace:

When I close my eyes at night, after such a seemingly endless day at sea, I see nothing but the undulations of shagreen, rhythmic and glittering blue, hear the sounds of slapping against the prow and fish gasping. Then it become a kind of opaqueness, divested of detail before the darkness of sleep gathers and dreams entangle me ordering their fragments into spurious clusters that nevertheless carry their own murmurings of destiny. (113)

There’s no jarring transition between the “real world” of Mina, the fictive world of Daisy’s story or Mrs Dalloway as the referent. Cahill creates threads that link these three ‘texts’ perfectly, so that it feels as though they are all one seamless story, paralleled in time and space. The dramatic irony is that both Daisy and Mina are equally fictional, creating a metafictional aspect to the work. Cahill does a wonderful job of not only reckoning with the difficult questions that come out of Mrs Dalloway, Woolf’s diaries and other material of the time including Woolf’s nephew Julian Bell’s affair with writer and academic Shuhua in China, but also picking up some of the more sumptuous aspects of Woolf’s writing. There is a cadence here, an interiority and a poetry which pays homage to Woolf’s style:

Like wind gusting through Gordon Square. Or like waves breaking, nearest to the shore while at the same time from a farther current, the sea sucks and swirls in pools of rocks, each break overlapping the last, till the ocean’s ink becomes a hammer, striking, smashing, throbbing against the sand, and a wave drumming upon the ear’s membrane, against the page: this is how writing happens. (168)

A basic familiarity with Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway will certainly increase the resonance, and there is much pleasure to be had from the correspondences with that text, but it’s not mandatory. Cahill provides a complete story for Daisy and Mina and many of the key questions that come out of this book stand alone, as does the sheer beauty of its narration. Daisy & Woolf is a wonderful debut, and one which doesn’t shy away from contradiction even as it draws the reader into its deeply compelling narrative.