Reviewed by Tina Jayroe

Reviewed by Tina Jayroe

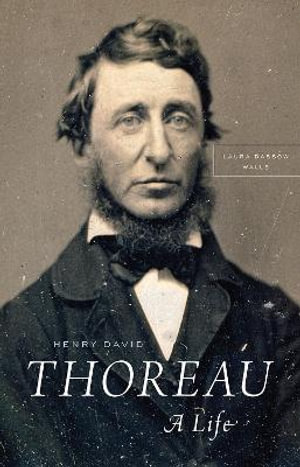

Henry David Thoreau: A Life

by Laura Dassow Walls

The University of Chicago Press

July 2017, 640 pp., ISBN 13: 978-026344690

“Everyone who comes to Thoreau has a story,” is the opening sentence from author Laura Dassow Walls: the person who has managed the incredible feat of providing us with the most robust, interesting, and intertwined yet sequential details of his entirety in Henry David Thoreau : A Life. It has been labeled the definitive biography to date about America’s most famous transcendentalist, and its author is the recipient of multiple awards and accolades for it.

There are a vast number of books about Henry Thoreau (1817–1862). I have read a handful of them plus a fraction of the extant articles, essays, blogs, lectures, and works he himself authored about his own existence. This book differs from those in the way it delightfully fills in the blanks left by all the rest.

From the start I knew this was different. Walls begins with both the geology of Concord, Massachusetts and genealogy of the Thoreau family and how those two aspects of the universe formed and evolved many moons before Henry was even born. Then, moving through the book, I felt ecstatic and relieved to have many of my long-standing questions addressed. Some of those were:

- What caused his friendship with Emerson to run hot and cold?

- How much did he really do for the Underground Railroad?

- Did he ever swear or curse?

- Who was the woman who proposed to him?

- Why did he change his name from David Henry to Henry David?

- How often did he lecture and what determined their frequency and locations?

If you consider yourself a “Thoreauvian” you will enjoy Walls’ ability to craft poetic-sounding sentences that make you feel like you are partially drifting into the pages of Thoreau’s own sentence structure mastery. For example:

Thoreau understood nature as a higher truth encompassing the self and society, a dynamic truth shot through with all forms of life swirling around and collecting themselves into a whole with Walden, not Thoreau, at the center. In these pages, Walden blossoms as a holograph of the planet and of one human life, lived as a prism refracting sunlight onto the page. (352)

She also consistently highlights Thoreau’s lifelong and deep appreciation of Native Americans and we learn just how much time he spent collecting information for his planned book about them:

Henry had uncovered the fire-scorched stones of an Indian campfire, proving the students’ conjectures. Before they left, he carefully replaced the turf to cover up their find, ‘not wishing to have the domestic altar of the aborigines profaned by mere curiosity.’ (99)

Thoreau never missed a chance to praise Indians and defend them against the prejudices of his friends. . . . he asserted that his Indian guides were as reliable as white men. (419)

His contempt and disdain for slavery and “manifest destiny” are also present throughout—with a section specifically focused on his dedication to the life, cause, and reputation of Captain John Brown:

Frederick Douglass had been scheduled to speak at Boston’s Tremont Temple as part of the popular ‘Fraternity Course’ lectures sponsored by Theodore Parker’s congregation, secular lectures held on Tuesday evenings for the public. Douglass had long worked with Brown but had refused to join, or support, the Harpers Ferry raid. But when Brown was captured, his pocket held a letter from Douglass, evidence implicating him directly. A warrant went out for his arrest, and Douglass fled to Canada, leaving the Fraternity Course without a speaker, whereupon Emerson wrote to the organizers recommending Thoreau’s ‘Plea for Captain Brown’ as a replacement. . . . The recommendation did its work. On November 1, Thoreau carried his ‘Plea’ to Boston’s Tremont Temple, where 2,500 people gathered to hear him. Thoreau stepped to the podium and calmly faced the sea of faces. ‘The reason why Frederick Douglass is not here is the reason why I am,’ he opened. For an hour and a half he held his audience enthralled, an audience that broke in, time and again, with spontaneous applause. (452)

I reveled in this book because, unlike others before it, it is not fragmented, incongruent, or just a compilation of interesting facts. But rather, it reads as though Thoreau lived much more recently and the author had interviewed in-person, first-hand witnesses to his life simply because it flows from birth to death without a sense of missing information or lapses in time. On any given page you may learn about the weather that day or how late Thoreau stayed up as if it were all recorded and timestamped on videotape for the author to view and re-view.

One of the most interesting aspects of the book for me was not even about Thoreau, but about the progressive town of Concord and its inhabitants and activities. There were many different and engaged citizens experimenting with alternative schooling, non-traditional worship, provocative publications—along with the constant meetings, charities, and cooperative communes that supported these endeavors. To learn about what was going on at that time and place was impressive and depressing: impressive that their efforts were encouraged and supported by so many; and depressing that we have not sustained that momentum, which Walls explains, was not easy to produce:

joining this revolution meant one’s own education would never end: one should find discussion groups and forge networks to explore and share new thought. . . . it took real courage to break with generations of convention. (97)

If you do not know much about Thoreau except for his famous quotes, his cabin on Walden Pond, and an essay on civil disobedience but want to know more, then this is the book. It is not a succinct, sporadic, time- or subject-limiting depiction of Thoreau like other (very important) biographies of him are. Instead, it is a comprehensive look at a non-conforming 19th century New Englander who had varying and quite commendable attributes; each affecting one another. Thoreau was a naturalist, botanist, philosopher, educator, poet, gardener, inventor, caregiver, activist, abolitionist, surveyor, traveler, historian, brother, son, friend, mentor, rebel, reformer, and yes . . . Captain of Huckleberry Parties.

Laura Dassow Walls said the Thoreau she sought was not in any book so she wrote this one, and we should be grateful for it. She brings to light the ingenious sage and prophet that I always knew was there, but who had yet to be fully exposed. The world needed a definitive biography of Thoreau, and now it has one.