Reviewed by Mary Ellen Talley

Reviewed by Mary Ellen Talley

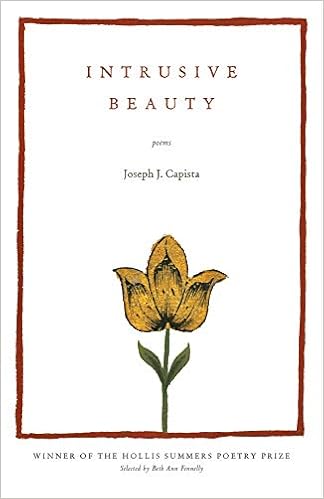

Intrusive Beauty

by Joseph J. Capista

University of Ohio Press Athens

ISBN 139780821423769, 79 pages, 2019

There is a symmetry of language along with the compassion of ministry in Joseph J. Capista’s debut poetry collection, Intrusive Beauty, winner of the 2018 Hollis Summers Poetry Prize. The title leads one to wonder what that beauty is intruding upon – perhaps upon pain and cruelties of human nature.

Capista begins his collection with an egret, a cloud, a gull with a beak like an oyster knife in the poem “Telescope.” Here is the color of purity and hint of inevitable violence associated with nature. This color image repeats when we read the second poem, “Thaw,” about police finding a dead body as the no longer pure white snowdrifts melt, “It happens like this every spring.” Capista writes a narrative that includes references to many of his themes for this volume: children, cruelty, misfortune, ministry, love, and coming into adulthood.

Capista is a skilled poet. His verses command the satisfying circularity of those first two poems, the variety of free verse lines, lull of assonance and repetition, questioning of a philosopher’s observations, mesmerizing rhymes occasional or throughout a poem, and pages sprinkled with sonnets and villanelles. All this while including enough narrative for the reader to appreciate the speaker’s call to veer headlong into lives of those he wants to help.

There is a kind of coming of age in many of these poems, but not of early youth. These are poems of the coming of adulthood. They show a young adult living in substandard housing while observing and serving others. Capista writes in “Thirtysomething Blues” an eloquent villanelle recalling how “It’s not the risk we mind, but consequence. / To do without at twenty-two was ‘in.’ / Yet now we’ve had, to have not stings. We wince.” // Later, the poet describes a baby in a crib in “For a Daughter” while citing “a dew that moistens dust along / our rotted sill and clouded glass.” As the poem, “Thaw,” ends in “cold,” this poem ends with warming of the cold.

Children are scattered throughout this collection. Of those he teaches writing to, such as students at a camp for children with severe burns, he describes one surly girl in “Malaprops:”

I’d never seen the niche

a surgeon sculped in

her wrist so she might grasp

a pen, though “grasp” perhaps

is not the best of words.

From observing youthful cruelty on the streets of Southwest Baltimore, the speaker in “SOWEBO” observes from his window a boy named Angelo leading a passel of boys. Angelo stops a bike rider to say he likes his bike “then yanks the boy mid-wheelie, plucks him / by the collar, then pounces him down Hollins / Market’s marble antebellum steps give it to me.”

Capista warned us cruelty would come in an earlier poem, “A Child Bird-Scarer,” an ekphrastic poem about a boy in a Victorian print whose job it was to scare birds from a newly seeded field. “Sometimes a cruelty rose in me / I could not tell apart from all / I pitched at them.” This is one of several poems about artistic endeavors or pieces of art, poems that integrate artwork with the poet’s themes.

One gathers from poems in section two that Capista spent a year of Jesuit service following college working at a Montana school for troubled boys, particularly during an autumn when fires erupted in forest lands nearby. This poet is an observer, a witness, as accentuated by poems in the collection about photographs as well as students who reside in the shelter. Read closely and we see these kids in “In the Event of a Fire” had fires of their own from home to contend with as:

Ash drifted through

the bedroom, delicate gray remnants

from some encroaching violence we ignored,

fell soundlessly on cigarette-scarred arms

and chokecherry cheeks. I shut the window,

drew the shade. No, they didn’t even wake.

Such poems allude to the reasons for his ministry. In “Gut-Bomb,” we learn that when roadkill became available, the shelter staff jumped at the chance to use the meat. Of course, as a boy complimented staff on the “gut-bomb burger” he then spat out something that “sounded remarkably like buckshot.” Yes, a colorful and revealing poem, but what stands out is “medication logs of children / we forgot to let be children. / I knew all I could fix was supper.” What a realistic observation about compassionate ministry. And, as in other poems in this collection, roadkill is another kind of violence.

The poem, “Manifesto,” a superior ars poetica poem begins cleverly, “Form: shape of the poem, shape of the chip / on your shoulder. Art doesn’t need you. / It doesn’t want to be your friend.” Capista goes on to compare poetry to the visual arts. The poet is philosopher as he notes that unlike with poetry, in the visual arts “we see the whole before we see each part.” This poem reads almost as an appealing aural lyric essay. But let not the teacher take himself too seriously:

we persist my spouse and I have been

here since the moment we were tall enough

to ride this ride swans are actually very

aggressive creatures just do as they say so

nobody gets hurt a poem is anything that

demands a certain way of looking at nothing

and this deepness around us is dark hey guys

it’s listening time not talking time, okay?

I think you might mean domineering

but I’ll try to be less “diamond earing.”

I’ll try to stick that in a stupid poem.

The above poem mentions a spouse. One gathers that besides working with children, a couple has sought to become parents. There is a miscarriage in “Cornicello,” a reflective sonnet with a sad end, “Of course we lost the baby. Life’s uncharmed.” thus uniting the speaker of the poems with youth of misfortunes who needed his education and guidance.

There is delight in this collection as well. We read of a daughter. The poem, “Kid Happens” is a light respite and celebratory, “We can’t conceive / by logic’s axe, for instance; / they happen and we praise.” In one poem, “On Music,” a completely rhyming poem on /er/ sounds with repeated phrases, we see a “further father / Cooking dinner” debating volume of music “(Motion faster, volume lower. / She’s the dizzy toddler spinner.) / I prefer my crooners louder.”

The final poems tie themes in the collection together: children, cruelty, service, love, and coming into adulthood. The speaker philosophically considers the lives of students afflicted with misfortune. In the poem, “Composition,” we read “What I like about my students is that they aren’t yet the sum / of their worst actions, that they define themselves / not by what they’ve done but by what they’ll do.” For an educator or service provider to youth to read such lines provides an “aha” moment of recognition.

Later in the same poem we read of the speaker’s college roommate who lost both parents suddenly. The poet wonders how his friend “has learned to love the world” and whether he is “terrified by those in whose arms he lies or whether // He terrifies them with a violence he did not choose,” a sentiment one might share after reading about or dealing with children from these poems who reside at medical camps or youth shelters. This poem is bookended in front with a love poem and then as the book closes with allusions to a child rhyme “Twinkle Twinkle” and William Blake’s “Tyger, Tyger” in “As If the Lullaby Is for the Child” as the poet reveals that the hopes of childhood are for all of us.

About the reviewer: Mary Ellen Talley’s reviews have been published in Colorado Review and Compulsive Reader as well as forthcoming in Sugar House Review and Crab Creek Review. Widely published in journals such as Raven Chronicles, U City Review and Ekphrastic Review as well as in several anthologies, her poems have received two Pushcart nominations.