Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

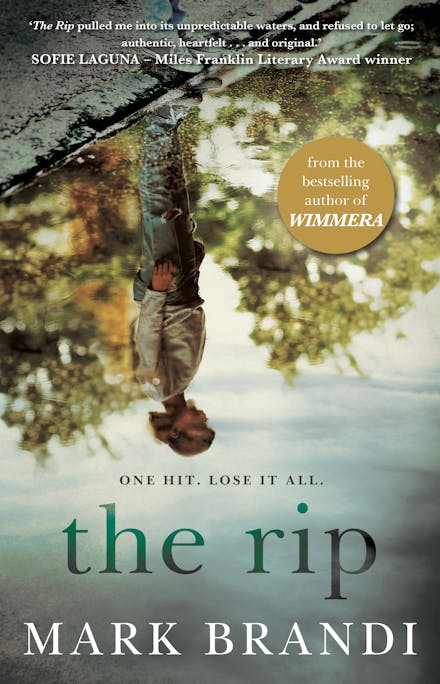

The Rip

By Mark Brandi

Hachette

ISBN: 9780733641121, Feb 26, 2019, $29,99

I was a teen about the same age as The Rip’s protagonist during NYC’s late 1980s homelessness crisis. We learned to look through the increasing ‘bundles of clothing’ on the streets, to think of the people under those bundles as somehow different from us, and to keep moving, quickly – we were busy after all – always rushing somewhere. I couldn’t turn a blind eye to young people on the street though. It was too confronting; too close to home. It was impossible to look away, or to pretend what I was seeing wasn’t an alternate reality for me, or that my own clean, safe apartment, regular job given to me by my uncle, and the university education I was getting weren’t mostly the result of the lucky hand I was drawn. Victoria had about 25,000 homeless people when the census was done in 2016 (the number would be higher now), and it’s not a stretch to imagine this as a true story. The Rip forces the reader to look closely, not as a sympathetic passerby, but as participant. Brandi uses the voice and point of view of a seventeen year old girl living rough in Princes Park, Melbourne, with her dog Sonny and friend Anton. The girl, whose name is not revealed until nearly the end (and who I’ll refer to as “the protagonist” as I think her namelessness is important), is intelligent, thoughtful, and intensely observant, as as street kid would need to be to survive, and her story feels real and emotionally intense – it’s hard not to love her. But she’s also addicted to heroin and sometimes does sex work to support her habit. Her repeated mistakes, and the help she doesn’t take creates a deep innate drama that works perfectly in conjunction with the terrible crime that crackles around her, putting her in even greater danger than her addiction.

Anton looks out for the protagonist – takes care of her and keeps her somewhat safe and helps her get food. He’s a young guy who reckons he looks like Dave Navarro from the Hot Chile Peppers, but like the protagonist, he has an addiction- in his case, painkillers. The two of them are far from comfortable, and every day is a struggle to survive – from staying clean, finding food, and keeping safe from predators and prejudice – but there’s a tenderness between them that constitutes domesticity. The two of them, who remain platonic, dream of getting a place of their own and living a clean, safe life together.

These characters are possibly in the worst situation it is possible to be in, arriving there via abuse, misfortune and bad choices, but they are reasonably stable, until a character named Steve comes along and offers them a place to stay in exchange for the proceeds their begging. Like many of the people they meet, Steve is volatile, dangerous, and the protagonist doesn’t trust him, nor does she entirely believe the story that the terrible smell coming from his room is the scent of meth cooking. In spite of her increasing danger, and worsening situation, the the protagonist remains philosophical and self-aware, unafraid to explore the state she’s in with a kind of calm detachment, that one hopes will ultimately save her:

I thought the dragon was the first hit you ever had. It was that warm, weightless feeling you never saw coming, when everything suddenly made sense, and you thought nothing would ever worry you again. That was the dragon. And we’re all chasing it, even if we know, deep down, we’ll never find it again. (107)

The narrative moves quickly, driven by crime story that lurks around the edges of the book, and the protagonist’s own arc as she grows. Danger is always present. It can be minor, such as a shopkeeper who moves them along and calls the police, or the dealers and abusers looking to take advantage of the two young people. There is kindness too – from the police officer “Dirty Doug” to Major Perry from the Salvos. Perhaps the most confronting is the pity that the two receive from people like you and me, who look away, or assume the the protagonist is unable to understand much. In fact, the protagonist’s perceptions are sharp and rich – her observations creating a strong sense of inner Melbourne as she moves through the daily cycle of day and night:

It’s almost dusk and I can feel the chill on my skin, but it’s good to sit and watch people go past. They’re all heading for Flinders Street Station, like some long river of dark suits—going from their office, or their shop, or whatever, to catch a train to take them home to eat ans sleep and do it all again tomorrow, and maybe the same thing every day forever. (77)

Brandi doesn’t look away, nor does he flinch from what is ugly or painful in this harrowing but ultimately affirming novel. There is no rose-tinting of the protagonist’s situation, and who gets to survive and who doesn’t is also often arbitrary. The Rip presents a confronting look at the way our society perpetuates the dangerous situations that the protagonist finds herself in. She is repeatedly failed by the institutions that are supposed to protect her – like her foster care, or housing shortages. She never blames anyone for her troubles though, and always treats her problems as temporary, and born out of the tragedy she endures and the ensuing abuse, which we find out just a little about. Brandi’s prose is consistently beautiful, and the story itself remains compelling and fast paced. The rip metaphor is repeated like a refrain throughout the book, and creates a strong connection between the reader and the protagonist. The Rip is an intense, important read, shining a light on an area that has not been the subject of much art, and encouraging deep empathy, understanding and engagement.