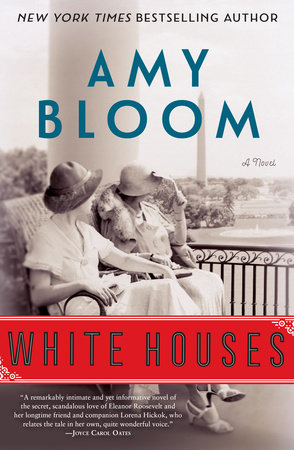

White Houses

by Amy Bloom

Random House

Paperback, $17.00usd, Nov 06, 2018, 256 Pages, ISBN 9780812985696

2018

Subject matter and style combine to make Amy Bloom’s latest novel outstanding. The salty yet poetic narrator of White Houses makes this historical romance, in memoir form, engaging and moving.

When journalist Lorena Hickock and U.S. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt became romantically involved in 1932, they dreamed of a life together a cottage on the Roosevelt estate, where “the kids would come to see how happy I made their mother…[and] our love would create its own world,” as Lorena puts it. Sadder but wiser, she reflects: “It’s not true that if you can imagine it, you can have it.”

The novel opens on April 27th 1945, two weeks after the death of U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Lorena (“Hick” to her friends) is, at Eleanor’s invitation, preparing Eleanor’s New York apartment for a weekend together. This weekend is the present of the story, the through line to which the many memories and flashbacks are attached. In 1932, Lorena, who worked for the Associated Press, interviewed Mrs. Roosevelt, wife of the New York governor and president-elect. Her first thought on seeing Eleanor in a cheap blue serge dress and flat shoes was, “In the name of Christ, who dressed you?”

Eleanor, the niece of former President Theodore Roosevelt, came from a wealthy (though troubled) New York family. Hers was a world of private schools, multiple homes, European travel and genteel volunteer work. Though privileged, she suffered from low self-esteem and grief over her parents, then an unfulfilling marriage and a domineering mother-in-law. Lorena, in contrast fought her way up from a Nebraskan girlhood with an abusive, impoverished father. At fourteen she was supporting herself as a housemaid. After writing press releases for a circus, she joined an aunt in Chicago, attended high school and found employment as a newspaper reporter. By 1932 she was the best known female reporter in the United States.

As Lorena covered the Roosevelt story, the women’s love affair developed. After a honeymoon road trip to Quebec and Nova Scotia, Lenora gave up her career in journalism to become chief investigator for the Federal Emergency Relief Organization, a department of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, and moved into a room in the White House near Eleanor’s. Celebrating her arrival over drinks, the president said, “Much better to have you inside the tent, Hick, and pissing out.” He preferred that she be a member of the family, so to speak, a keeper of the family secrets rather than a journalist in quest of a sensational story.

When the Roosevelt children were still young, Franklin, then Undersecretary of the Navy, had an affair with Eleanor’s secretary, Lucy Mercer. Eleanor’s mother-in-law persuaded Eleanor not to divorce him and ruin his career. Soon after that, Roosevelt contracted polio on holiday at Campobello Island, Nova Scotia, and lost the use of his legs. Though he and Eleanor were friends and allies, their intimate life ended and their marriage became open. Franklin had a longterm relationship with his secretary, Missy LeHand, along with close friendships with several female cousins and a Danish princess in exile in the White House. Meanwhile Eleanor associated with lesbian couples.

Lorena moved into the White House looking forward to Eleanor’s company as they waited for Franklin’s four years in office, or perhaps eight, to be over. In fact, he was president for twelve years, and a few months before his death, was elected to a fourth term. Meanwhile, Eleanor, as his envoy, had limited time with Lorena.

Lorena took the fate of another live-in member of the family as a warning. Missy LeHand suffered a stroke and convalesced for a while in the White House, where Eleanor, not Franklin, saw to her care and visited her regularly. Later, at her sister’s Massachusetts home, Missy pined for the president, who never telephoned or visited. “If Missy’s stroke hadn’t killed her,” says Lorena, “Franklin’s cold heart would have.”

Naturally Lorena is subjective, althought historians have written that Franklin’s affability and charm hid a selfish, determined core. One must remember that he was coping with a disability and deteriorating health while pulling his country out of a depression, then leading it through a world war. As Doris Kearns Goodwin shows in her non-fiction work, No Ordinary Time, Eleanor played a vital role during these national crises. Lorena, however, wants to be Eleanor’s “lover and mistress” rather than a “dear friend” or the “White House pet” and leaves the White House after four years. (Later, when in financial straits, she comes back at Eleanor’s invitation.)

Away from Eleanor, Lorena “learned to do all kinds of large and small tasks with part of [her] missing.” A live-in relationship broke up because her partner accused her of still being in love with Eleanor. Lenora never quite managed to divorce the Roosevelts. Of Franklin’s death, she says:

Franklin was a terrible husband, an unnerving friend, my rival, and my president. I had kissed him on his birthday one night and he had held onto my hand and I was, for that minute, as in love with him as any of them. He’d left us in a half hour between lunch and dinner when we’d let down our guard and now we were all sick with grief.

In a compelling scene, Bloom shows Lorena seeking out Franklin one night in March 1945 to say goodbye. “So you and the Missus – the fire’s gone out?”he asks. “When the time comes, you’re the one she should be rocking on the porch with…You’re the one… Don’t give up on her. Don’t be so proud.” At the New York apartment, Lorena wonders if, perhaps, she can fulfil Franklin’s last wishes. Earlier, when someone asked if Eleanor was the great love of her life, she said,”She seems to be”. To “Are you hers?”, Lorena replied, “Close enough.”

The women’s weekend together is interrupted by a cry for help. Parker Fiske, a fictional Roosevelt cousin, shows up at the door with his lover, battered and beaten, after being arrested in a nightclub for “disorderly behaviour and other things.” Could Eleanor telephone Mayor LaGuardia of New York to let them have their passports so they can flee to Mexico? Eleanor tells Lorena that she won’t “squander the little influence that she has” with the mayor, “Not for this.” Aware that their own affair would cause a scandal, Lorena asks Eleanor, “Should we be in jail?” This is the turning point, where Lorena realizes that Eleanor wants to preserve her husband’s legacy and make a contribution on a world stage. In a parting scene to rival the one in Casablanca, she gives Eleanor permission to be all that she can be:

You have such a big life ahead of you…and I’ll be at home on Long Island, cheering like crazy, clipping your articles, waving to your plane overhead…Someone’s gotta sit on that porch.

While the writing in White Houses is excellent (especially the use of flower and sea imagery for the lovers’ heart-to-heart experiences), it is Lorena’s unique voice that makes the novel feel authentic. Her sense of self-worth is impressive, considering the era in which the story takes place. Her decision to be who she is and be proud of it begins when she was fourteen. As a teenage office worker with a circus, billeted with “freaks” such as the Lobster Girl and the Alligator Girl, she resists coercion by a performer to be part of a “half man/half girl” act. Knowing that she’s not a freak, she leaves for Chicago. Throughout the novel, Lorena accepts every aspect of nature and stands up for herself.

Since the novel is presented as Lorena’s memoir, it naturally gives her impressions of Eleanor, and anyone expecting otherwise will be disappointed. Readers uninformed about the Roosevelts might want to do a little internet research if the time shifts get confusing. Franklin and Eleanor’s extramarital relationships were an open secret during his years in office, and have since been written about extensively. Bloom, who did research at the FDR Presidential Library and Museum and in their Archives, acknowledges that Blanche Wiesen Cook’s biography of Eleanor Roosevelt inspired White Houses. The novel is an emotional journey that will touch the hearts of all romantics, regardless of their sexual orientation.

Ruth Latta’s Grace in Love (Ottawa, Baico, 2018, info@baico.ca) is a romantic historical novel about a woman in Canadian politics.