Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

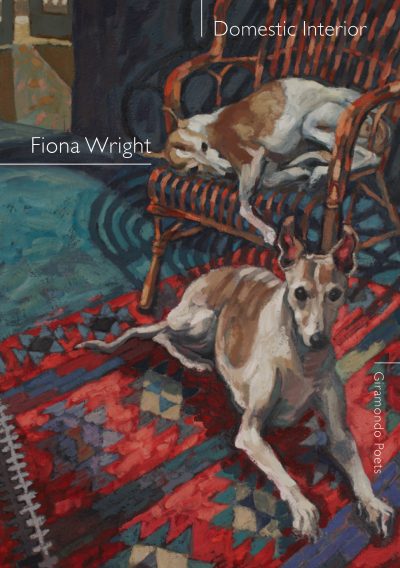

Domestic Interior

By Fiona Wright

Giramondo

ISBN : 978-1-925336-56-6, Nov 2017, 96page, $24aud

There’s a deceptive simplicity to Fiona Wright’s poetry in Domestic Interior. It’s the kind of poetry that is immediately accessible, inviting the reader into the everyday spaces and a perpetual present tense, even when the moment is past. As the title of the book suggests, one of the things Wright does exceptionally well is to conflate the domestic or familiar with the moment of transformation. This is often done through contextualising something sacred into a new situation, often built around location. The first section “Origin”, is all set in Sydney, and moves about the suburbs, pitting the observation of the everyday against high art: a Vermeer painting, formal love poetry and forms like Centos and sonnets against shopping centres, t-shirt slogans, a beer at the pub, a bloke-y barbecue, and the hard-sell of a Tupperware party. The humour in these poems becomes a double-edged sword that call attention to the superficial solace of consumerism, and fast food consumption. The reader is encouraged to laugh at the antics that form a backdrop to an ordinary Australian life in Sydney, but underneath is a dark undercurrent where any moment, children can get hurt, alcoholism slides from social to anti-social, and consumerism becomes an imperative to hide a pervasive fear and loss of control that pivots around food and illness – recurring themes that form a thread between Domestic Interior and Wright’s 2015 book of essays Small Acts of Disappearances, written at the same time:

Crossed at your black-socked ankles,

your wrists, you saystubbornly

(not responding to treatment)

the beautiful girl can’t be happy. (“Vocab List”)

There’s something of the flâneur in the following chapters, as the poems involve walking to and from home (“How do these houses hold us — according to our bond, no less”), through city streets, between suburbs at night, and to and from a variety of events, motion heightened by solitary, precise observations. Other people jostle, play music, carry on conversations, go on and off of trains, drive cars, and eat. Domestic Interior pivots around food. There isn’t a lot of eating from the point of view of the main persona or subject. Eating is something that other people do, or that is dreamt about, thought about, picked at and discussed. Food is present in shop windows, on counters, or at the end of a spoon. The little bit of actual ingesting that happens is primarily liquid: a sip of gin, several cups of coffee (with saccharine), sparkling water, and lukewarm wheatgrass juice. There is almost a hyper-vigilance in the observations, in the careful perceptions edged by a crackling vulnerability:

I watch a woman in pink boardshorts

hold out white bread for a spring-loaded terrier,

an ancient cyclist on City Road with bubble wants

mounted on his handlebars, although they say this place has gentrified: mutation’s

never simple. (“After Mutability”)

The observations are visceral, coming from within a strong sense of the body. Thinness and its relationship to illness is a continual theme, though very different to the analytical approach of Small Acts of Disappearance. In Domestic Interior the perceptions are simultaneously more delicate and more intense, drawing the reader directly into the deepest heart of pain. The body and its relationship to food informs nearly every perception. There is a discount offered for waxing skinny legs, skinny fingers, thin arms, luminous pale arms, fingertips, a consciousness of the “salt of our own skins”, a small frame (“too big/to fit my frame”), small body curled, a hollowness, ribcage, and easy bruising, all of which makes the speaker’s vision seem both precious and precarious. Though there’s a familiarity to the city poems – an urbane understanding of places and spaces that is as fresh as Frank O’Hara’s Lunch Poems, the “Elsewhere” section extends outward, continuing the walking, the observations, but changing the setting to something less comfortable:

I watch miners roll their maps

Into screw-capped pipes, and I know I’m portable

InsteadI walk for hours past long, striated windows, willows,

Along overpasses, loosened and alone. (“All the Way from (Perth Poem)”)

These poems move past Sydney suburbs to Katoomba in the Blue Mountains, and further, to Foster (“Wallis Lake”), Perth, the Riverina, and Berlin, where Wright did a residency. Like many of the poems in this collection, there is a dry, wry wit that runs through them, whether they are parodying the Tupperware party, the city hipster (“My god, I’m missing my barista”), or getting drunk in a Berlin bar. Even at its most irreverent, there’s an understated modesty; a desire not to be too big, too loud, or lacking in subtlety, even as in in the section titled “A Crack in the Skin: On Illness”, it channels some fairly serious poets – Sappho, Sylvia Plath, and Jo Shapcott to name a few. One poem, for example, parodies TS Eliot’s “The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock” but in way that uses Eliot’s phrasing and humour to explore the indecision of anorexia (“restaurants of insidious intent”):

They try to fix me with a formulated phrase.

They say it could have all been worth it

But this is not what I meant.This was never what I meant.

This is not it, not it at all. (“Her Arms and Legs are Thin”)

Domestic Interior continues to hark back to the title, pivoting death defying acts of everyday survival around the domestic power of observation, the familiar landscape, and above all of the power of friendship to heal:

I had only trivialities to say.

But it’s the trivial things

that feel so weighty now andeven miss itself is

so tiny

a word (“Phone Charger”)