Reviewed by Sabrina Barreto

Reviewed by Sabrina Barreto

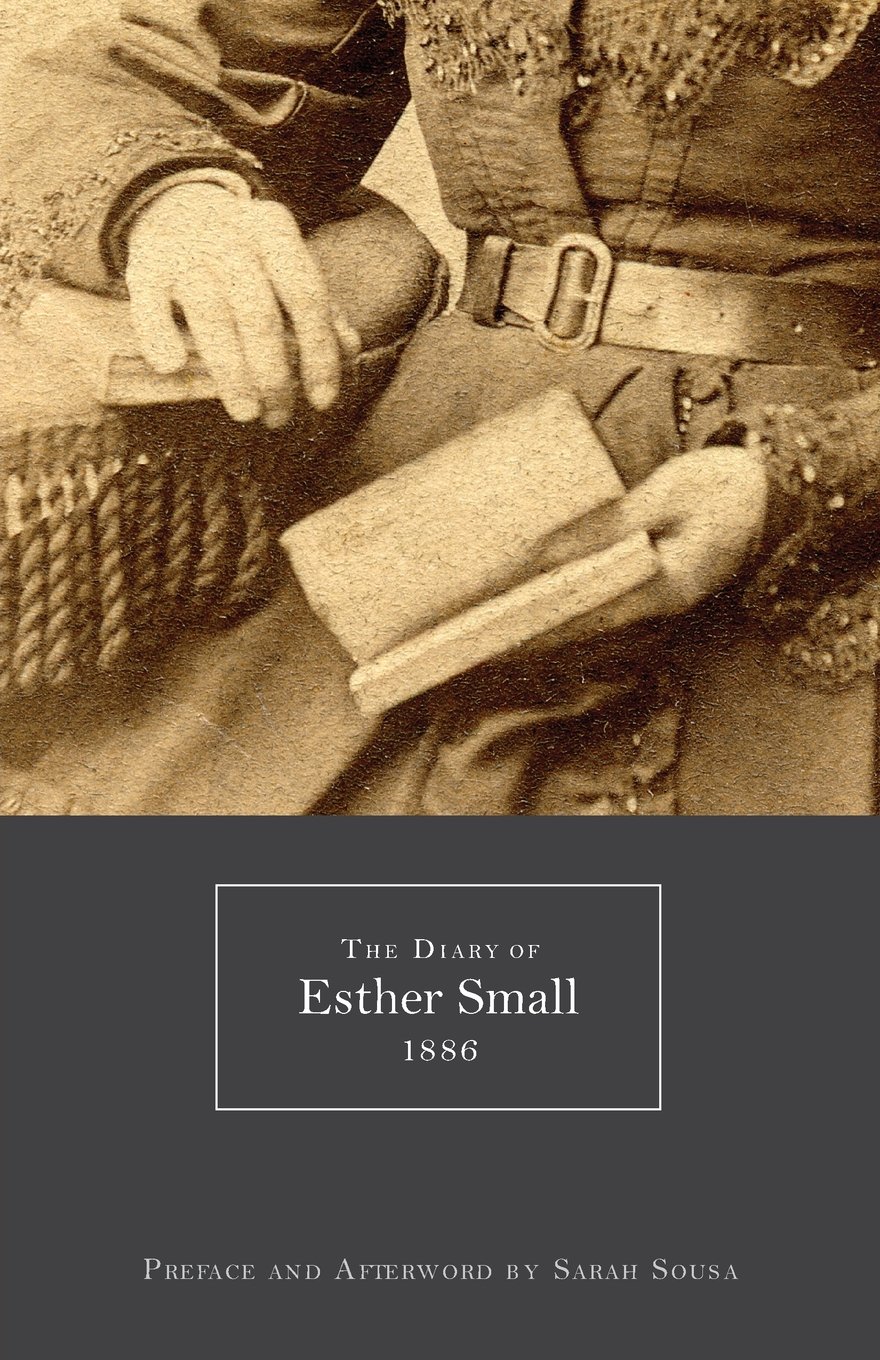

The Diary of Esther Small 1886

edited and transcribed by Sarah Sousa

Small Batch Books

ISBN-13: 978-1937650391, Paperback, May 2014, 105 pp.

In 2008, poet Sarah Sousa was perusing a Maine antiques shop when she stumbled on two pocket diaries. Contained within three by five inch leather flaps and written in near-inscrutable cursive, the black volume was dated 1880, the red 1886. The first had scant entries, but the red diary was full – here hid the story. Between the covers of 1886, stoic farmwife Esther Small recorded her arduous life, detailing each instance of domestic abuse from her Civil War veteran husband and father-in-law, while omitting her age on her birthday (forty-two) and her burgeoning pregnancy (months four through eight).

Sousa was not simply intrigued. She was invested. She deciphered the entries, sleuthed the cemetery records and censuses, and extensively researched nineteenth century women’s diaries, as evidenced in her luminous afterword on the subject. Surpassing the role of transcriber of Small’s logbook, Sousa became conservator and steward of the archive of her daily life.

It was particularly ideal for a poet to discover Small’s diary, as Sousa’s lyrical sensibilities toward the text are apparent. In fidelity to the limitations of the pocket diary, she preserved the entries’ original line breaks, and in fidelity to Small’s writing – itself an act of rebellion amidst oppression – she retained the misspellings and baroque syntax and diction. The line breaks are especially significant because Small wrote in a diary no larger than a cigarette case, resulting in as much physical restriction as mental restraint in her writing. The more clipped and frank, the more wrenching, as in the following successive entries about her husband:

he up and kicked

me a few times as hard

as he could on my bottom.

It hurt so much I could not set

down unless I had a cushion. (20)[The next day]

still lame can

not sit down

unless I have a

cushion (21)

Consequently, the reader not only feels the constraint, but moreover the poetry of Small’s entries. Each day reads like an Emily Dickinson poem. Small wrote her diary entries in spare, crystalline prose that is as revelatory as it is heartbreaking. With little space on the page and lesser time in a day to write about her internal life, she instead records her weekly chores of washing and sewing, churning butter and tending livestock, and raising children. She writes of loneliness, exhaustion, and violence, such as the suggestive:

So homesick

tonight I had to cry.

Am all beat out

and tired. (27)

Yet Small also writes of how monotony and assaults are punctuated by relaxing visits to neighbors and moments of plainspoken beauty, from “…First / sleigh I had this winter” (15) and “Silas Wright stopped / here and said I / could have the molasses” (31) to the following note after visiting a friend:

It seems like

going home to go

there. Came back

Just dark. (25)

At a slim one hundred pages, the book is a quick read – it can be read in a day or two leisurely sittings – but Esther Small’s diary haunts, fed by her clarity, simplicity, and subtle omissions. The book is further fortified by Sousa’s inclusion of photographs of the original diary pages and exterior, and moreover, her thorough and provocative afterword on 19th Century Women’s Diaries. In the essay, Sousa provides historical background from the outset, but its force lies in her probings of creative self-disclosure as a second-class citizen, female identity and the interlocking spheres of private and public, and the dovetailed responsibilities of a researcher and role of a reader. Her afterword reminds readers of the import of undervalued epistolary literature: their immediate power to form a deep, intense connection between past and present.

As both a historical document and literary work, The Diary of Esther Small 1886 is a volume that begs to be read by women young and old, by American history classes, by anyone curious in first-hand life experience from the past. Famous figures may have altered history, but the common civilians, baking pies and hewing trees and going about their everyday lives, are history’s bloodstream. No life is ordinary – and it’s understated books like these that deserve to be bestsellers.

About the reviewer: Sabrina Barreto is a Bay Area wordsmith and MFA Poetry candidate at California College of the Arts in San Francisco, where she served as International Editor for literary journal Eleven Eleven. She has received the Academy of American Poets Prize and two Ina Coolbrith Memorial Poetry Prizes. Her work appears in The Bohemian, The Santa Clara Review, the Sigma Tau Delta Rectangle, and the forthcoming anthology Allegro & Adagio: Dance Poems II.