Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

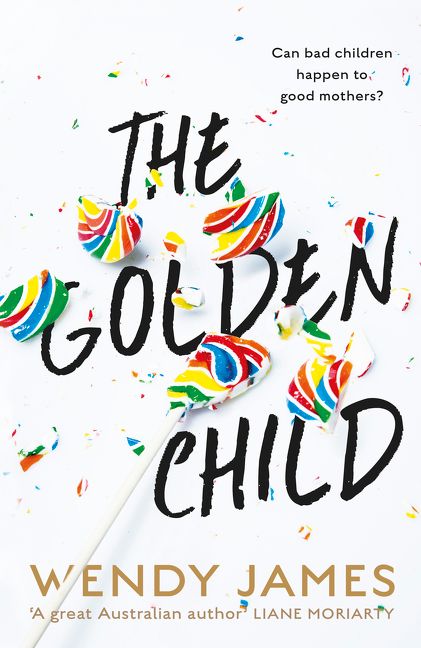

The Golden Child

By Wendy James

HarperCollins

ISBN: 9781460752371, Paperback, 352 pages, $32.99aud, Feb 2017

Wendy James does a marvelous job of capturing the neurosis of modern life in her new novel The Golden Child. She pulls no punches in her exploration of social dynamics among teen girls, and picks up on both the positive and negative elements of social networking, blogging, cyber-bullying, online narcissism, face-to-face bullying, and the particularly insidious way that young teenagers will play against one another’s insecurities in order to bolster their own fragile egos.

The book is exceptionally well-written, and the story flies by, lightened by the blog posts of protagonist ‘mummy blogger’ Beth Mahony, aka DizzyLizzy.com, an Australian expat who has been living in the US with her husband Dan and two daughters Charlotte and Lucy, blogging about her experiences, including the family’s return to Australia when Dan gets a transfer. The plot moves fast, the narrative driving the reading towards its final unnerving twist. It all happens almost too quickly. James’ writing is so smooth, and the story so powerfully plotted, that its easy to miss how neatly the shifts are between the individual voices, the many delicate links between cause and effect and the parallels between adults and children as we move from one character to another, the way the reader is unwittingly drawn into the toxic culture of privilege that underpins these characters, or how subtle the thematics:

It isn’t the way it happens in films or books: there is no clear demarcation, no real before and after, no particular moment, no instant when everything changes, no point of no return. No line has been drawn in the sand that Beth can look at and say: there, on one side, lies the past, all good; while in the here and now all is chaos. Instead, there’s been a slow accretion of moments, a gradual dawning that things aren’t what they seem. (257)

The balance between the interior musings and rationalisations of the characters and the front they present in their various roles is just right. As the family’s notions of “perfect” and comfort start to unravel, the dramatic irony increases almost to the point of cognitive dissonance. Beth’s blog becomes a recurring trope for how reality is constructed, and this is offset by another unsettling blog called www.goldenchild.com, which presents the machiavellian and unpleasant musings of what we come to know as the antagonist of the story. However uncomfortable the story gets, and it can get very uncomfortable, as the ‘true’ nature of the characters are revealed through their monologues, there is always a lightening thread of humour in the way the characters pick at one another:

Your sister has four kids, but that hasn’t stopped her from working, not for one minute. I don’t understand why you have this desire to sacrifice yourself, when you have so much, so much, going for you.’ (48)

The parallels in the relationship between Beth and her mother, and Charlotte and her mother seem so natural that it’s easy to miss how clever and tightly woven they are. James handles the complexity perfectly, working the transition in settings, space, and place perfectly, playing off the tension between the online world and the ‘real world’. The class system that the characters buy into is ever present, from the contrast between privilege and marginalization to the high school strata. In both instance, the rules of engagement are cruel, arbitrary, and oddly close to the bone:

Against Sophie’s pariah status her gift means nothing – as Amelia has pointed out, piano is the most pointless musical talent you can have, right? It’s not as if it will ever make her famous – it’s not like being able to sing or, even better, dance. (136)

The power structures are repeated and reinforced in fractals that work through the immediate family dynamics, the extended family dynamics, the adult friendships and networks, the schoolyard dynamics, the online world, and even the power structures typified by Beth’s former boyfriend and boss Drew, who is running for political office. Though the book is one of James’ least physically confronting, no one is murdered in The Good Child, it’s one of the most chilling. The ease in which the bullying escalates, or in which the status quo is returned to, and the utter logic behind that return, is not easily shaken off.

Though some of the scenarios in The Golden Child may seem extreme, it’s close enough to reality to leave an impression that doesn’t dissipate once the book is finished. The speed at which genuine warmth and connection are handed over for safety, power, convenience and acceptance mirrors the dynamics of modern life. There’s nothing didactic about The Golden Child. There are no clear villains, not even when it becomes clear who is driving events. There is only one mistake after another, each one manipulated and justified in ways that make sense in the context of the individual narrative. The Golden Child is a superb and very sophisticated novel that is both compulsively readable, and deeply resonant – a powerful combination.