Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

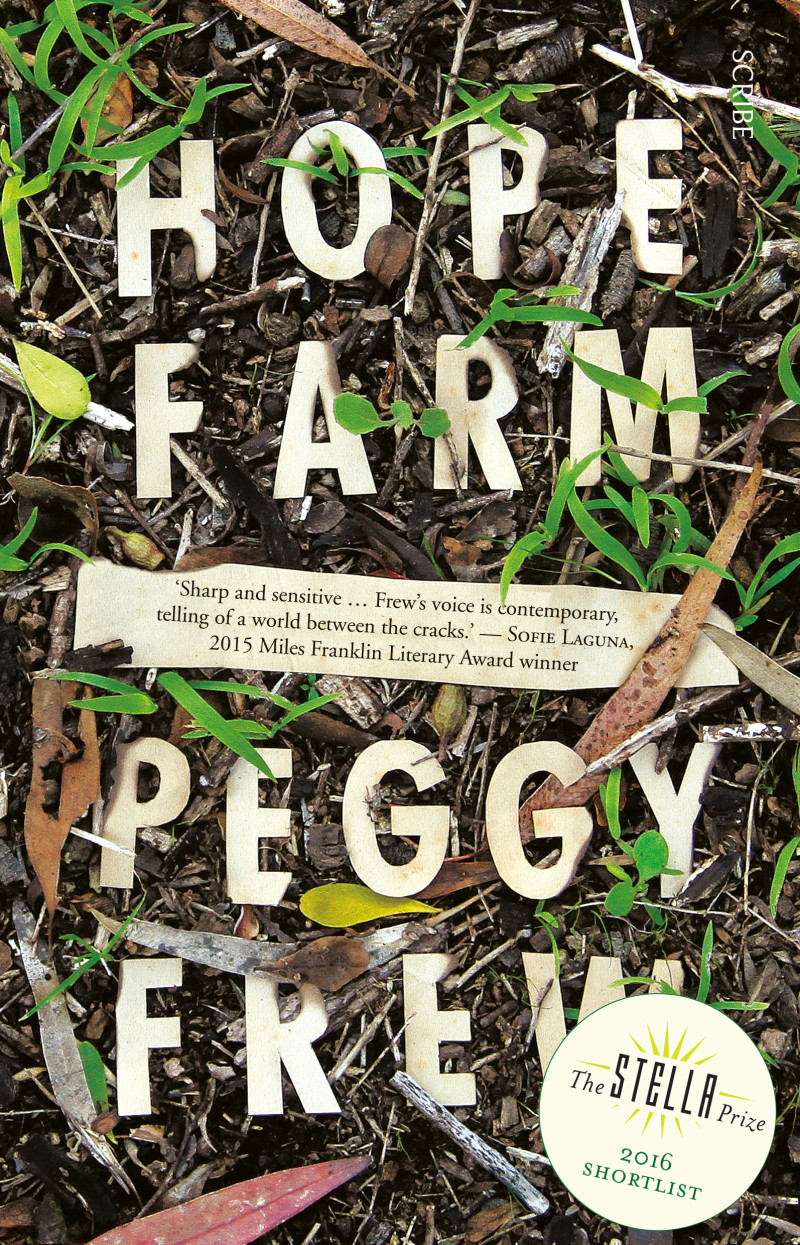

Hope Farm

By Peggy Frew

Scribe

Paperback, 352pp, ISBN (13):9781925106572, RRP:$29.99, 23 Sep 2015

I’m sure I’m not the only reader who felt an uncomfortable pang of familiarity reading Peggy Frew’s Hope Farm. Perhaps that’s because the late 70s and 80s were a peak time for Personal Development Groups and of the sort that my mother became engrossed in – Rajneesh, Hari Krishna, EST – there were a swag of them. Swami Sachidananda’s Integral Yoga Institute was the one my mother attached herself to, and I can recall many an afternoon babysitting my younger brother in a back room at the centre while my mother chanted, did free work, or attended “Satsang”. Peggy Frew wasn’t an ashram child, but she does a brilliant job of capturing what it’s like to be dragged along as an extra on a parent’s self-serving quest for Nirvana. Hope Farm mostly takes the point of view of thirteen year old Silver, who is is forced to follow her young mother Ishtar, as they move from one ashram or commune to another, each one slightly less comfortable for Silver, usually involving Ishtar in a new romance and Silver having to accustom herself to a new school. The transitions end at Hope Farm, ironically named as it’s the most ramshackle commune of them all, with a run down house sitting amidst a garden of weeds and dying ideals.

Interspersed with Silver’s narrative are journal entries which, though not named, quickly become obvious as the voice of Ishtar. The second narrative becomes a parallel story to Silver’s, both addressing themes of power and abuse and of love and aphasia. The two narratives inhabit the same landscape though not the same timeframe, and the disconnect between them creates a strong tension in the book as one explains the other, while also reshaping the characterisation as we’re discovering it.

Throughout the novel, Frew’s writing is consistently beautiful and rich with poetic imagery. Silver’s observations are sensual and detailed as she begins to discover the wilder parts of Hope Farm’s surround, along with a growing awareness of her own body:

The hut, the bush, the creek; the soft eruptions of blossom that swayed, damp and ragrant, as I went out with the bucket in the pink mornings. The band of sweet, moist air that sat over the water’s surface, coating my hands and forearms as I plunged the bucket in. The push of my thighs as I stood, made a scoop with my palms and drank. The taste, mineral and ancient, sent me down in the brown water, into that sinewy, tail-flicking world, layers of silt and ooze, secret opening in the flanks of rocks. (209)

Though the book moved me to tears several times, Frew never slips into pathos. Silver’s stoicism, even at the height of panic and fear, becomes a buffer to the uncomfortable world she is thrust into: one that incudes extensive drug and alcohol use, overt sex, and very little in the way of routine, stability, or parental care. The underlying exploration of memory and the mother/daughter relationship provide the undercurrent to this story and adds a great deal of depth:

In and out she dips, in my memory, wheeling like a star, cutting the chill, dank air of the farmhouse. Bleary with sleep, I pull back the rough fabric of the front curtain to glimpse her getting into one of the cars, the white puff of her breath in the grainy morning light, the sweep of her hair, the belt of her coat trailing. I am always just missing her. In passing she might touch me, run a quick hand across my shoulder blades, kiss the top of my head, pull me to her so I feel the brief softness of a breast of the point of a hipbone. And then I am released, as on she goes, and on, to the next thing. (129)

The reader is reminded, in brief snatches between the story’s progression to its intense climax, that these are the recollections of an adult, and not a child. Both Silver and Ishtar struggle with the inequality of their status, from Ishtar’s mother and the nuns at the home where she is sent to give up her child, to the unnamed mechanic in Ishtar’s narrative who Ishtar’s mother never even thinks to blame. There are the school bullies who brutilise Silver’s friend Ian and tease Silver, and many others who take advantage of Silver and Ishtar’s powerlessness. Miller, the violent and damaged antagonist of the story, becomes a representation of the oppressors for Silver (and Ian), and he pays for his brutality, but the world that Silver and Ishtar inhabit is one where small-mindedness, misogeny, and prejudices abound, both within and outside of the commune communities and perhaps above all, Ishtar and Silver’s own acquiescence – the internalised sense of shame:

‘Hippie Shit’ became my nickname. I spent morning tea and lunch in the library, was picked last in Phys Ed, and when we had to make pairs in Science, I was always with one of the freaks. But this was all bearable. I was used to it. I was cloaked in layers of difference, thirteen years deep; I didn’t expect this not to go unnoticed. (77)

Hope Farm is an exquisite and powerful book that explores the gaps between desire, societal norms, and love, loss, and memory. Both Silver and Ishtar’s story is deeply affecting, and as full of beauty as it is of verisimilitude.