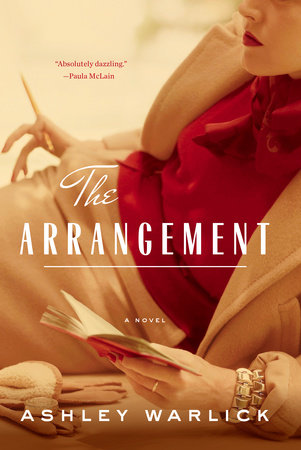

In a scene from the new book The Arrangement, a fellow guest at a dinner party asks aspiring writer Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher (who would later become esteemed food writer MFK Fisher) “What do you write about?” Mary Frances’ answers simply, “Hunger. I write about hunger for all kinds of things” (166). That sentence captures the mood and tone of Ashley Warlick’s latest novel, a fictionalized account of the complicated relationship between Fisher, her husband Al, and Al’s best friend Tim (real name Dillwyn) Parrish long before Mary Frances made a name for herself as a respected food writer.

The Arrangement begins in 1934, when Mary Frances Kennedy and her husband Al Fisher are working to build a life in Hollywood, newly returned from an extended stay in Dijon, France, where, by all accounts, Mary Frances discovered her passions—food and writing. Al, a poet and professor, is trying to establish himself in either (or both) the literary or academic communities but finding lackluster success.

It is indeed hunger that drives Mary Frances and the complicated web of a relationship she builds with her husband and his friend. The web grows to include Tim’s starlet wife, Gigi, and soon the constraints of what they’ve created begin to chafe all of them. The “arrangement” in question is never made explicit, but the fluidity of their living situation and the clear attraction between the three of them—Mary Frances, Al, and Tim—is largely self-explanatory. Gigi, whose presence looms large early in the first chapter, gradually fades as she finds other lovers more to her liking. Yet she and Tim maintain a fragile bond throughout much of the rest of the novel; however, it is clear that Tim is biding his time until Mary Frances is ready to make some sort of decision. Does she want to stay married, or leave Al and commit to Tim forever? If written by another author, this situation could be immature, or handled irresponsibly; the characters could easily come off as one-dimensional or juvenile. But Warlick somehow makes it work—clearly, each character is an adult, fully aware of their own minds, emotions, and desires. The problem is—should they follow their hearts and claim the lives they truly want, or continue living lives that suddenly seem false?

I loved Warlick’s gorgeous first novel, The Distance From the Heart of Things, and have been eager to read more of her work. Warlick’s bio mentions her work as editor of a food magazine, and her lush, detailed style is well suited for this type of writing. Reading one of her novels is like biting into something rich and decadent—it is something to savor. Her writing style is a sensory as well as literary experience—she brings the reader fully into the smallest moments of a scene. Consider sentences like “She’d discovered tangerines. They could not be peeled too carefully, each velvety string stripped away, the bright sections left to dry atop the radiator on yesterday’s newspaper while she took her bath and brushed her hair. The tangerines filled the room with their perfume, and when they were tight to bursting in their skins, she opened the window and nestled them into the snow piled on the sill to eat when they were cold, changed somehow for all the care she spent on them. And not to serve or share, but care she’d spent for herself. Alone” (68). Or, “Without Al, Mary Frances discovered what she did alone…The elements that mattered most were the simple ones: butter, salt, a thick plate of white china and a delicate glass, the music faint, the feel of paper in her hand, and the knowledge that there was more, always more book to read, more wine if she liked it, some cold fruit in the refrigerator when she was hungry again, and the hours upon hours to satisfy herself” (113). Or, how Warlick describes Fisher winning over her potential publishers: “They loved her. They loved how she traveled and read and pulled from all corners. They loved how she was not Mrs. Something Something, and her manuscript not like anything else they’d ever seen, written by a woman or a man” (173). Her writing is something to read carefully, so that it can be fully absorbed, or possibly read a second time to catch the full impact of each scene.

Warlick does not portray Fisher as a shy, demure young woman. Rather, she has a strong sense of self, and while she realizes the consequences of her actions and the impact of her decisions on others, she is unapologetic about her choices. While not established as a food writer until later in the book, Fisher’s confidence in her abilities is obvious; with Tim’s encouragement and tutelage, she is ready when the publishers make an offer. Of course, the Fishers’ marriage faces the strain of success, especially since Al’s efforts have fallen short. To say that watching his wife achieve many of the goals he’d set for himself was humbling is an understatement to say the least. But I didn’t get the sense that Warlick was portraying Mary Frances as a faultless human being; rather, Mary Frances was very aware of her weaknesses (insatiable hunger and passion), yet was still trying to somehow use them as strengths. Finally, she succeeded, by giving a voice to not only her desires, but one desire everyone has in common—food. And not just eating it, but food for its own sake. Carefully selecting the perfect ingredients for a recipe, or admiring fresh produce and seafood at a farmer’s market, cultivating a garden…essentially admiring everything we consume.

The food itself is a secondary storyline, yet it ties in perfectly with the doomed love triangle. Like most passionate love stories, Mary Frances’ relationships do not end happily. Yet, as most writers know, every experience is the basis for additional material, and Mary Frances is no exception. Her great love would influence her writing for years to come, as Warlick explains: “The notebooks are full of little gems she never knew how to set, and she loses herself to them constantly, whole afternoons slipping away. She reads this page, and here, suddenly, is Tim..She has written about Tim for years now. Hasn’t she always written about Tim? He haunts her, and she lets him, she writes him into places he never was: beside her, all around her…” (69).

The Arrangement spans the years 1934-1943, with an occasional jump to the late 1980’s and early 1990’s when Fisher was in the late stages of her career. The jumps in time were a bit disconcerting at first, but Warlick keeps them to a minimum, and it does provide some context as to how Fisher’s career progressed. But some important details about Fisher’s life are not revealed; it is clear that there were some secrets even she wanted kept to herself, so whether Warlick takes any artistic license with the ending is unclear. Warlick does an admirable job of painting a vivid, detailed portrait of a complicated, progressive woman who was ready to speak her mind in a voice all her own.