Reviewed by P.P.O. Kane

Reviewed by P.P.O. Kane

Fritz Kahn

By Uta and Thilo von Debschitz

Taschen, 2013

ISBN: 9780230313828

Nature imitates art. Or, to express it in another way, our understanding of nature, and above all perhaps our own nature, is necessarily metaphorical. We can only understand the unknown through the known, through what is close at hand, our human habits and cultural practices, artifacts and inventions. So the invention of the pump preceded our understanding of the heart’s function and the emergence of the computer led in time, and not too much time, to the founding of a new discipline: cognitive science. It dawned on us that the mind is a computer. Nature imitates art.

Fritz Kahn was a popular science writer who was most prolific in the ‘20s and ‘30s. His masterwork was Das Leben des Menschen, a five volume study of human biology which appeared between 1922 and 1931. As with all his works – and Kahn continued to write about many different fields of science right up until the early 1960s – these volumes were heavily illustrated. He would design the illustrations and various artists – some known, others unknown and uncredited – would draw them, according to his specifications. One thing we do know is that ‘Man as Industrial Palace’, perhaps his most famous design, was illustrated by Fritz Schüler:

Der Mensch als Industriepalast (Man as Industrial Palace) Poster, supplement to Das Leben des Menschen III, Franckh/Kosmos, Stuttgart 1926 (subscription ed.) and 1929 (trade ed.), Fritz Schüler. Copyright: © Franckh/Kosmos Verlags-GmbH & Co. KG/TASCHEN

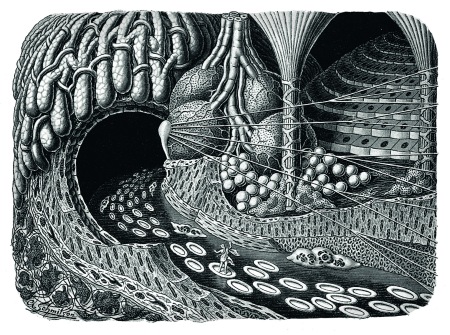

This book contains just short of 350 illustrations which have been taken from Kahn’s works, together with a small selection of articles he wrote for various publications. If the latter are characteristic, then it is clear that he had a strikingly visual writing style. One, entitled ‘Einstein Sonata’, reads like a script for a film: a cosmological epic. While another, ‘Fairy-tale Journey on the Bloodstream’, most closely resemblesFantastic Voyage (the old Raquel Welch film) recast as a feuilleton, if you can imagine such a thing. Arthur Schmitson’s accompanying illustrations have an eerie flavour, their landscape reminiscent of some of Alfred Kubin‘s works:

Einfahrt in eine Drüsenhöhle (Entering a gland cave) Das Leben des Menschen II, Franckh/Kosmos, Stuttgart 1924, pl. XXVI, Arthur Schmitson. Copyright: © Franckh/Kosmos Verlags-GmbH & Co. KG/TASCHEN

There is a certain quality that’s more typical of the bulk of Kahn’s illustrations, mind, and you might even go so far as to call it his signature. I’d describe it as a kind of surrealist conceit. He takes the metaphorical, model-building mode of thinking that lies at the heart of science and uses it to raise a smile, provoke thought and (ultimately) aid understanding. In one illustration, for example, he will show how a diatom is like a church window; a feat of which Ernest Haeckel, not only a great scientist but an extraordinary artist, and author of the wonderfulKunstformen der Natur, would have approved. While in another he will compare heat insulation in a man and a thermos flask (!). My particular favourite (perhaps an acquired taste, I concede) sets out to show that ‘the octopus lives in the position of a man hanging from a horizontal bar’. Now, how can this illustration and others like it fail to raise a smile? This is the poetry of incongruity a la Lautréamont. Here’s a further beautiful example, showing an insect’s wings unfolding like a parachute:

Die Entfaltung der Insektenflügel (The unfolding of insect wings) Das Buch der Natur II, Albert Müller, Rüschlikon/Zurich 1952, p. 100. Copyright: © Fritz Kahn/TASCHEN

One might well ask: ‘Is this science, and does it matter?’ Of course, the images can be enjoyed for their own sake but it is a question that must be addressed. We should start by looking at where Kahn was coming from. He sought to popularize science, his goal was to communicate his passion to the reader, to fire their enthusiasm for the subject. And he found a unique way of doing so. By contrast, a working scientist aims for objectivity and strict accuracy. And yet… and y

et note that even scientists cannot do without images of some sort. As Peter Galison writes: ‘By mimicking nature, an image, even if not in every respect, captures a richness of relations in a way that a logical train of propositions never can.’ Or again, in a reflection on the scientific enterprise itself: ‘The richness of the image and the austerity of the numerical are always falling into each other.’ Incidentally, some of the science here seems dated and/or dodgy yet the images, by and large, continue to delight and astound. Art has a longer shelf-life.

And a final thought to end: if you substitute the homunculi in the ‘Man as Industrial Palace’ poster above with a flow chart of some sort you would have what is virtually a cybernetic model of man. Since the poster dates from 1926 and cybernetics from 1948 or so, that would be a truly extraordinary case of nature imitating art.

Fritz Kahn is a beautiful book, full of thought provoking, fascinating images and laden with not a little humour.

About the reviewer: P.P.O. Kane lives and works in Manchester, England. He welcomes responses to his reviews and you can reach him at ludic@europe.com