Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

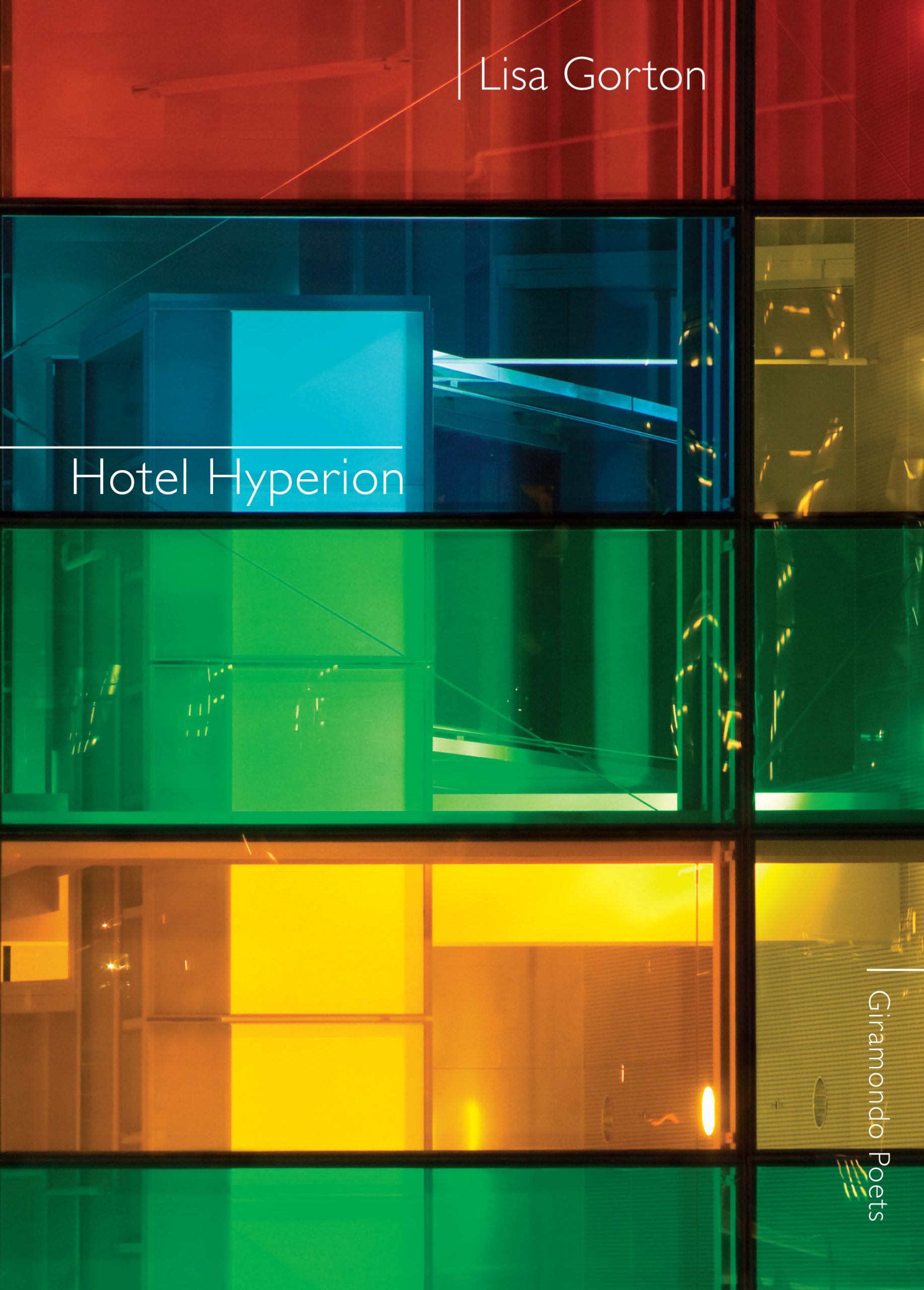

Hotel Hyperion

By Lisa Gorton

Giramondo

64pp, $24, ISBN: 9781922146274

A room can be any distinguishable space within a structure, but Lisa Gorton’s Hotel Hyperion takes the notion of a room to the grandest of metaphorical extensions, turning rooms into universes, into compartments in the brain, into moments of time and pockets of space. Hotel Hyperion is relatively short at only sixty four pages, but it is so densely packed that the work begins to expand into inflationary meaning as you go deeper into the poems, reading and re-reading. Though each of the poems stands alone and indeed many of the poems in the collection were published individually, there is an underlying story that links the work together. This is a story of memory, loss, history and hubris. It’s a story about a new future and about the relics of the past that travel with us and are left behind as we transform – individually, and as a species. The poems are self-referential, memetic – with cultural ideas and motifs travelling from one poem to another, and metapoetic in a way that is somehow both humorous (at times) and profound.

The book is structured into five sections. The first “Dreams and Artefacts” is built around the Titanic Artefact Exhibition held in Melbourne in 2010. It is possible to see each of the sections as rooms, and each poem as a smaller room or contained within a room. The rooms are literal – a windowless interior: “where Perspex cases bear,/each to its single light, small relics – “ but they’re also metaphoric: “a place less like place than memory itself –“. The Titanic is recreated in rooms that reference other rooms. They are real relics but they only exist in that dreamlike place of memory. In the ‘now’ of the exhibition, the clock has stopped, the staircase goes nowhere and the cities are imaginary: “slow-mo historical epics with the sound down,/playing to no one.”

The next section, “The Storm Glass”, takes its subject, a scientific instrument that was used on Darwin’s voyage on the HMS Beagle, as the starting point. The Storm Glass was used to forecast weather through the condition of the liquid in its glass, presented in this context as a small sealed room. The liquid in the glass undergoes alchemy, changing and folding in upon itself to create a mini world, which is mirrored later in glitter filled snow domes. Though glass is a solid substance just as a room is a solid container, it is able to fold into itself – a modern multiverse that might exist in a different spatial dimension, making itself only known through gravity. Though the old fashioned science might be embarrassing to the modern scientist: “it would embarrass/by the overconfidence of intention”, it has retained its aesthetic beauty thereby transforming science into art: “formalize the inwardness/of weather and contract hemispheres of wind//to a decorative instance.” At the end of this series, it is still raining, harkening the rain at the end of the previous sequence. We are the reader who is “walking out into the garden,/into the long rain breaking itself against the glass,” participating in this art making and joining the world – the word made flesh. As we penetrate this room, we transform it.

There’s a new journey in the title sequence “Hotel Hyperion”. We’re in the room of the future- 2020, as a mother sends her son off to Saturn’s atmospheric moon. “Press Release”, with its double entendre title – being both “news” and the idea of letting go into the world. The poem is tender, infused with longing, regret and bravado. Though this is a futuristic scenario, the heartache is one that will be familiar to any parent who has watched a child grow. The melding of timeless sentiment with a future context creates a powerful impact, drawing the reader further into the poem and readying us for the shift of person and room that we find in the next poem. In “II The History of Space Travel”, the child has become archeologist, reminding us of the Titanic Exhibition as we encounter the “The Futures Museum”. The rain continues to fall as the series progresses – treating images from earlier poems as memories and bringing us in and out of rooms that function in multiple ways – as worlds, as prisons, as spaceships, as places in the past that might or might not have existed and as containers for the present. The story that unfolds is evocative and oddly believable, but also surreal. The mingling of these disparate sensations creates a strong tension that drives the poetry along.

“Room and Bell” present a series of prose poems, growing around the artifact of a bell. There is so much going on in this series – nostalgia in the desire for home, the bending of time and co-mingling of past, present and future. At one point the past and the present converge through a mutual mirror:

“I know the room not as a place, not even as a memory, but as though some ghost of the future had whispered in my ear, ‘Here you are’, and permitted me to glimpse, this moment, the room as it will be when it exists only by my haunting.” (33)

The transformation is chilling and clever. In some ways this also harkens the folding universes of previous series as we fold into to who we once were.

The final series, “The Triumph of Caesar” contains a number of ekphrastic poems. There are brief snapshots written as a tribute to Diena Georgetti, Michelle Nikou’s tissue box sculptures, Roger Hiorns’ ‘Seizure’, and of course Mantegna’s painting, “The Triumph of Caesar”, which gives the section its name. Though these poems beautifully and tenderly refer to and recreate the art around which they’re built, they never lose the threads that bind this book together. The rooms, the rain, the folding universe, the compression and distortion of time, and that sense of scientific precision coupled with nostalgia are ever present. The poems grow outward built up of all the details of who we all are, who we’ve been and who we’ve yet to become – the story of the human race in its striking, precise frailty and beauty:

“Now nothing of the lived-in place

but like a work of memory, where the flood was, insatiate

the crystals mass edge upon edge and,

self-repeating, consume scale models of themselves

like facing mirrors, haunted by the rooms they make –” (43, “Homesickness”)

Hotel Hyperion is an extraordinary collection. It’s packed full of motifs and imagery that are both strikingly original and uncannily familiar – like something picked out of the reader’s own dreams. The poems are individually beautiful and evocative, and work perfectly as standalone pieces – calling to mind the themes around which they’re built. They also work within the confines (rooms if you will) of their sections or series, but when the entire collection is taken as a whole, and the reader moves from room to room, thorough time and space the end result is almost shockingly powerful and deeply moving.