Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

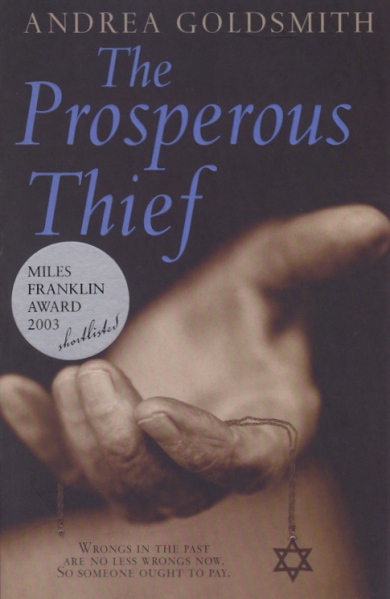

The Prosperous Thief

by Andrea Goldsmith

Allen & Unwin

Nov 2002, RRPA$27.95pb

ISBN 1865087564

The Prosperous Thief begins in 1910 with little Heinrick (Heini) Heck, born to a drunken mother and absent father in a seriously depressed Germany. He soon learned to survive in his dingy world, and in spite of his circumstances, takes care of his sister and brother, and takes advantage of the growing opportunities for young Germans offered in Hitler’s Germany. At the same time, the Lewins, a young well educated Jewish family face serious persecution as they desperately try to escape this new Germany where their young daughter cannot go to school and the future is full of danger. Andrea Goldsmith’s fifth book is an historical novel that looks at the lives of Heini Heck and the Lewins – the two opposing sides of the Holocaust which intersect, and the impact that this has on their children as the stories moves forward in time to the modern day. While presenting a compelling and powerful story, the novel explores a wide range of topics including crime, punishment, good, evil, pain, survival and the legacy that acts of these nature leave across generations in permanent repercussions.

The history is very well researched, and the novel rich in the kind of detail that brings historical fiction to life, from Heini’s futile attempts at making a living in the country:

“What had he done? The rows were perfect, all the vegetables sprouting. What had he done?

She was yelling at him and calling him stupid. Corn, she jabbed at one plant, beans, she jabbed at the next, potatoes at the next.

‘It’s a salad of a row,’ she screamed at him, and told him to get out before she set the dogs onto him.” (21)

to Martin Lewin’s fear as his family watches some Hassidic Jews get beaten:

They reach out, they replace their hats, mud dribbles down their old faces and snares in their beards. Again their hats are knocked off and trodden in the slushy gutters. And then the flash of a knife. Renate seizes Alice and pulls her off Martin’s shoulders, shoves her face into her skirts.(53)

The earlier characters are particularly well drawn – the Lewin family and especially young Alice present a very intense and personal look at the impact of the Holocaust on individuals, an antidote to the grand impersonal language which Laura later bemoans: “Etti’s words were heartbeats, but the public language of the Holocaust, in fact of all the horrors which pockmarked humanity, was diluted and disinfected in abstraction. Genocide. Persecution. Incarceration. Where were the perpetrators in all these words? Where the victims?” (151)

As the viewpoint shifts between Heini, Alice and Martin, often in flashback, we feel these heartbeats, and the direct impact of these events – and even become culpable, choosing our own survival with Heini, struggling to keep the family and soul together with Martin, and watching the world dissolve as we escape to England with Alice. Good and evil remain absolutes, but those capable of great evil are also capable of good, and those who are being oppressed can also make bad choices. The Prosperous Thief raises big questions without slipping into sentimentality or losing the thread of the story.

The later characters, Raphe and Laura are less engaging. Perhaps it is their own easy life purchased by the losses of their parents which make their struggles seem self-indulgent, or perhaps it is the difficulty of writing in the present, but both Raphe and Laura seem less believable. Raphe’s tortured relationships and obsession with his grandfather seems slightly contrived, as does Laura’s political involvement. Laura’s lengthy speeches on human rights seem designed to ensure that the author’s interests are covered, rather than stemming directly from the character. On the other hand, Laura’s interest in the oppressed – political refugees and aboriginals – is a nice parallel to her father’s role as oppressor. Her lack of knowledge of the past has resonance in modern man’s tendency to forgetfulness, both with heinous historical events like the Holocaust and with other forms of oppression such as what the early Australian settlers did to the Aboriginals. Laura and Raphe do work well together well as characters, mirroring each other. Laura has no way of getting to her history. Through her father’s shame, she has lost her past, just as Raphe has lost his through his grandfather’s death. The relationship between the two has tension and makes for very interesting reading as the power between them shifts.

Much has been written about the Holocaust, but Goldsmith’s novel still makes for a fascinating read. The book provides an original perspective that focuses on the social and economic basis of the Holocaust while also exploring big issues like good and evil and its impact on and the culpability of future generations, the search for self-awareness, healing of the past and the present, and how we achieve closure.