Reviewed by Amilya Robinson

Reviewed by Amilya Robinson

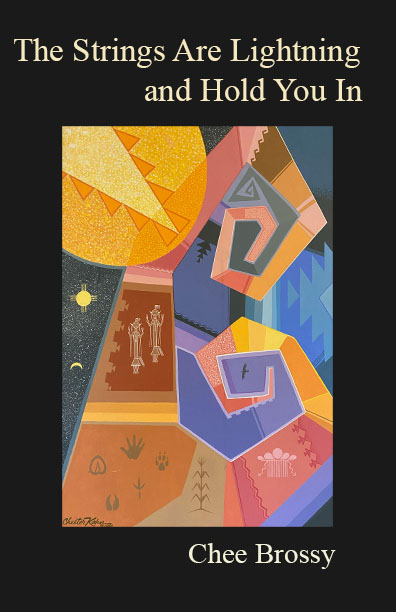

The Strings Are Lightning And Hold You In

by Chee Brossy

Tupelo Press

ISBN: 978-1-946482-76-1, Nov 2022, Paperback, $21.95

Shining Indigenous poet Chee Brossy brings the beauty of Diné culture and his experiences living and growing up in the Navajo Nation in Arizona to the page in a burst of philosophical, celestial magic, a vivid display of naturalism, and the beating heart of the Native community. His newest work, The Strings Are Lightning And Hold You In, is a poetry collection that transcends time and history, weaving stories of tradition with the unfolding events of the present, connecting the wild with the domestic, and masterfully interlocking the spiritual with the tangible. In this collection, words become a conduit for much more than a story and yet are almost too little to contain its incandescent quality.

Brossy begins with the waking of the world, the beginning of all beginnings and stories. In the first poem, “The Thawing of the World,” “moss,”, “reeds,”, and “grasshoppers” come forth from the ice along with the “glistening cicadas / chewing through a long hibernation” before any human ever takes their first breath (1). Reminiscent of the Navajo story of creation, “Red spiders crawl from tin cans / and weave the story’s tapestries” as the oral tradition dictates the red-clothed, black-eyed Spider ant people once appeared at the formation of the world (1). Brossy’s conversation with the natural world is effortless. His poetry transports the reader to a world untouched by human hands and it is breathtaking. As humans finally begin to thaw out themselves they “[succeed] only / in scraping the frosty layer of frozen meat / with a fingernail” (1). The imagery of the first people waking up from this hibernation-like state but still seemingly having a longer journey evokes a sense of healing, of adapting to a new world when everything is changing. I think it connects with the way the Indigenous community today still has a long journey ahead of healing and is a reminder of the stories they have yet to create. The poem ends with the line, “We say, Boy, you’ve come back” (2). This last line really ties up the introductory poem nicely. I felt the narrator’s feet stepping back into a place where they could harness these stories and experiences and I felt myself as the reader prepare to come along for a no-doubt worldview-shifting ride.

Another poem that exemplifies Brossy’s talent for weaving narratives together is “The Oort Cloud.” This story speaks of “The Twins” from Navajo tradition, heroes born from the Changing Woman and the Sun who “go searching for arrows, following Lights-up-the-Night among comets and ice songs we’ve forgotten—just gourd rattle and voice” (11). While they search, “songs are forgotten because even beyond Pluto they can hear ours about the Pueblo woman who came to the dances in Gallup, with long, untied hair and the rest of our lives we’ve been searching for her” (11). Some of the beauty that belongs to this particular poem has to do with the allure of change. The poem speaks to the ancestry of the Navajo people, of stories and songs long forgotten, while the people of the present continue forth with something new. It’s a sort of forlorn, nostalgic sensation of something lost but also something gained.

The next poem I want to bring to the forefront, “Do We Still Pollen Young Pines,” is one that is comprised entirely of questions that flow into each other as if each is but a larger part of one singular question. At the center of this poem is a focus on pollen. Pollen in Navajo tradition, can represent life’s journey, a cure, a resolution, or guidance. It speaks to ancestral and elderly duties to pass on wisdom to younger generations, to elicit change where it needs it, and to continue practices that nourish the earth and its inhabitants and enrich their lives.

“Do weeds still choke the stream at Black Rock Spring?” (26). “Does the hummingbird ever get out / Is horny toad still spiked / in our hands, our throats” (26). “Do we still pollen young pines / praying for height” (26). “Does water still gush from the spring’s pipe / Do we still fistfight for water / Does the circle of juniper branches stand from last year / Do we still see her bumping through the woods / Does wind still sound / thick and roaring through those trees?” (27). This poem, when I read it, invokes a sense of nostalgia, as if the speaker is someone inquiring after a home they’ve long left. Do things still go on as they have, terribly, beautifully, obviously just as the horny toad will always be spiked?

“Perfume I” and “Perfume II” were two poems that jumped out from the page because they seemed to take on a full-bodied personification of the senses. I can’t recall many poets who weave such vastly different emotions and feelings so seamlessly. “Our scent issues from our scalp, under our arms, between our legs. We all know, all hunt for it—even when perfume is sprayed, or lotion rubbed into skin—like searching out a melody among the static of twenty radios. The moon plays back our cries. The pleasure—” (32). This stanza is very much a sensual one that wraps its tendrils around the body, and the sensations of touch, scent, and sound. The idea that our scent as human beings is so ingrained within our physical and emotional selves is a captivating one. What intrigued me most about these two poems is how interconnected the scent of a body and of pleasure can be with the role of scent in grief, in the loss of that body and pleasure. I loved this concept of loss between lovers and “How a coat becomes a second skin,” in which the aggrieved “[knows] all the pockets, [their] own smell trapped in the lining…smells what hangs in her husband’s closet. Not washing, not giving away, not letting go” (60). Because smell and scent have carried such meaning in such a profound way, it is hard to accept the loss when the scent remains, even faintly.

The final poem titled, “Burntwater,” is like a grand painting, the style of words flowing like water, one image careening and bleeding into the next. I love how narrative is relinquished to vivid imagery at times and flows back and forth between each in a captivating almost hypnotizing way. “I taped him set the tape recorder between us on the table loved one do you understand the red light to catch every inflection throat clearing gravel” (71). Brossy ingeniously ends his collection of invaluable poetry with words and stories of the narrator’s grandfather. “She breaks free. Where is the order of the sun indifferent meaning beats down on us she is fluid in these last steps the trees melting into rock at the edge and leaps” (72). We learn tales of the trials of his youth and the story of when he met the narrator’s grandmother. “But in the house in the hogan where the skylight soft sun midmorning my grandfather cries and wipes tears from his face. His fingers look strange old and out of place against the face he rubs every morning to clear his eyes. I click the machine between us on the table slow but the echo of a gunshot and wait. We’ll stop here today” (74). The grandfather’s bleeding heart and yearning for the past is a beautiful, vulnerable ending to the collection. The Strings are Lightning and Hold You In is a breathtaking chronicle of ancestral Indigenous wisdom, stories, and authentic moments inspired by Brossy’s experiences all captured in the beautifully illuminating spotlight.

About the reviewer: Amilya Robinson is a senior at San Diego State University pursuing a degree in English as well as certificates in Children’s Literature and Creative Editing & Publishing. Currently, she writes creatively for SDSU’s first all-women-run magazine, Femininomenon, and edits for Splice, The Journal of Undergraduate Scholarship at SDSU College of Arts and Letters. In the future, she hopes to begin pursuing her MFA in Creative Writing for Fiction.