Reviewed by David Brizer

Reviewed by David Brizer

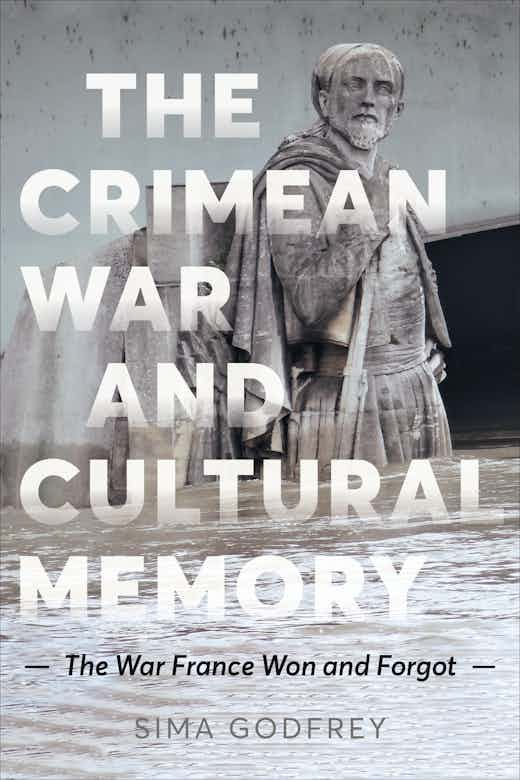

The Crimean War and Cultural Memory

The War France Won and Forgot.

By Sima Godfrey

University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 2023, 210 pp

Impressions d’Afrique de Raymond Roussel

Impressions d’Afrique de Raymond Roussel

Un Voyage Surréaliste à travers une Afrique fictive

By Raymond Roussel

(Independently published), France, 2023, 329 pp.

Many think of Rimbaud’s permanent exile to Abyssinia, usually attributed to rejection by Verlaine, as a basically romantic albeit extreme gesture. We like to think of that final desperate move as an act of self-effacing bravado.

Who knows? We weren’t there at the time. Perhaps young Rimbaud’s postscriptive thirst for lucre, for questing in the blinding sun at the diamond mines there, became the poet-maudit’s new driving force. What we do know – what has survived – is that the French colonial tradition (let’s not even get started here), formerly ‘embracing’ the world from the Middle East to the West Indies to Vietnam, was and is not merely geographic. In fact the it was and is hugely cultural, artistic and intellectual as well.

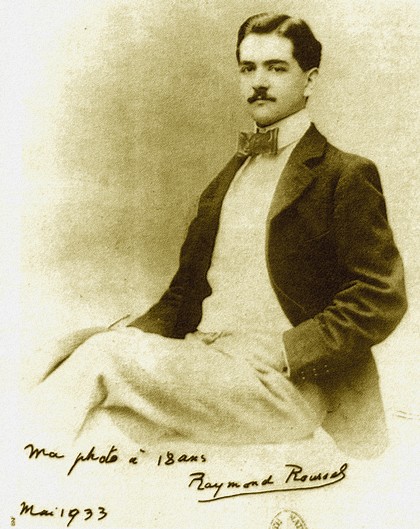

Raymond Roussel (1877 – 1933), lionized by surrealists worldwide, established a kingdom of the imagination geocentered in deepest ‘dark’-est Africa. This was an Africa born wholly of Roussel’s very congested imagination, populated by worm contests, inconceivably elaborate word plays, fakirs, and impossible quasi-futuristic technologies (Roussel adored Jules Verne.)

Raymond Roussel (1877 – 1933), lionized by surrealists worldwide, established a kingdom of the imagination geocentered in deepest ‘dark’-est Africa. This was an Africa born wholly of Roussel’s very congested imagination, populated by worm contests, inconceivably elaborate word plays, fakirs, and impossible quasi-futuristic technologies (Roussel adored Jules Verne.)

Roussel’s story is fascinating, in and of itself. Born into wealth, inheritor of his stockbroker father’s fortune, the eccentric young man devoted his time passion and finances – till they ran out – to putting up his plays, novels, and other writings. He was a loner, a dandy, an eccentric. He died at age 56, in a rooming house, of a barbiturate overdose, likely a suicide.

Later in his life, Roussel travelled widely. But he boasted widely too –‘None of thesetravels have gone into my writing. They are wholly products of the imagination.’ The products of his imagination soared. Roussel’s life and work, long obscure, eventually took center stage in the collective theatre of dreams: his work became the springboard, justification and cause célèbre for succeeding generations of surrealists and like-minded notables, including André Breton, Dali, Paul Eluard, and Marcel Duchamp, who unabashedly attributed his great glass work, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, to Roussel.

Roussel was an enormous influence on the Oulipo, and on Harry Mathews, another literary surrealist of note. Most central to this review, Roussel may now be considered Emperor or Mayor or Principal Freiherr of the Republic of Dreams. And what exactly is this ‘Republic of Dreams’? Is it the oft-fantasied Never-Never Land, inhabited by mystery, by darkness, by the Inexorable? Or is it the geopolitical reality of, say,15 million lives quashed in the Belgian Congo by the good offices of the over-the-top imperialist regime of Belgian King Leopold II? Is rampant genocide and grabby-ness the inevitable accompaniment of high European culture: witness the Congo, Algeria, Cambodia, Vietnam…?

This is where Sima Godfrey’s The Crimean War and Cultural Memory: The War France Won and Forgot, neatly fits in. In this audacious volume, Godfrey, a professor emirita of French at the University of British Columbia, attempts to account for the absence of French national pride in the events of that war (strangely contrasted, for example, by the British, France’s co-combatants against the Russians; the British celebrated victories at Sebastopol and related venues with poetry (The Charge of the Light Brigade), parades, fêtes, national monuments and street names. Not so the French. “To be fair,” as Godfrey points out, “the French too erected a monument from the melted iron of Russian canons captured at Sebastopol.” But that’s as far as it went. And the Crimean War (1854 – 1856 ) a premonitory war, an emblazoned warning sign for wars to come, featured, at least on the French home front, the onset of profound ambivalence and even derision toward pointless unjustified military campaigns.

War was the word on everyone’s lips. There was “talk of Russian aggression, expansionism, and eventual control of the Black Sea.” The year was 1854, but the sentinel warning already had a familiar sound. Hysteria and rampant yellow journalism touted possible hegemony of the Eastern Church over the Roman; a pretender had the (literal) keys to the church, and therefore to the Kingdom. This was unacceptable. Something had to be done, right?

One out of four French soldiers fell – some 75,000 – in all. Not good. Sima Godfrey muses, “Writing on the Crimean War in French culture, has often felt like I was writing a book about nothing, that is, about something that isn’t there.” Which oddlyenough reiterates similar pensées of Flaubert, who saw in Madame Bovary an opportunity to write ‘un livre sur rien’– a book about nothing.

The French pretext for the war was puzzling – all this over a contested set of Church keys? Godfrey advances a series of possible explanations, of hypotheses, for the historical erasure. Perhaps this inglorious war was Napoleon III’s, an attempt to rescue his name and reputation from the ash heap of mediocrity. And/or the Crimean War was only incompletely recollected by the French press and populace – there was no Tennyson, no Charge of the Light Brigade. There was, instead, the nightmare reportage on a French army decimated by typhus, short supplies, and therefore attrition. Further, the war was subjected to the winnowing process of collective forgetting.

The Crimean War and Cultural Memory is more than a window on cultural disapprobation, from a particular era. It is a sensitive, scholarly (with great photographs and illustrations) exercise in resurrecting obscure, ‘forgotten’ history. How history gets to forgotten is the main issue here. Think of Godfrey’s book worth every time the Figaros and Foxes of today pass judgment on critical events, and make so bold as to tell us how to think.

About the reviewer: David Allen Brizer is a NYC-based author and book critic. His articles and reviews have appeared in The New York Times, The New England Journal of Medicine, The American Journal of Psychiatry, Rain Taxi, others. His short stories have been published in AGNI, Exquisite Corpse, Word Riot, among others. Brizer’s non-fiction books include Quitting Smoking for Dummies, and Addiction & Recovery for Beginners. His second novel, The Secret Doctrine of V.H. Rand, will be published by Fomite in January 2024, a follow-up to his Victor Rand (2014.) At present he is working on a collection of short stories and a metafiction about literary surrealists.