Interview by Michelle Blankenship

Interview by Michelle BlankenshipWhat led to your interest in wet wounds?

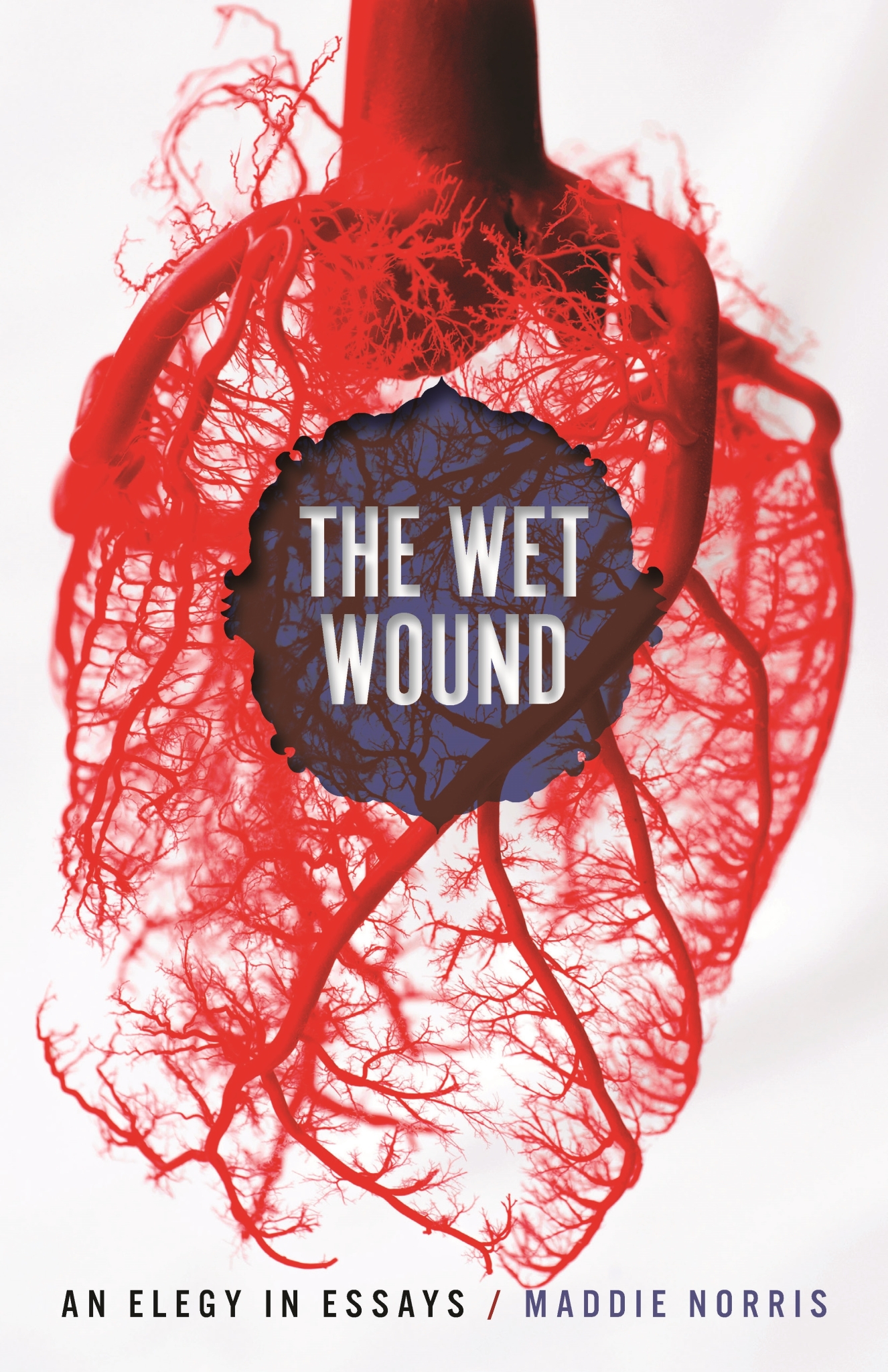

My dad died when I was 17, and I inherited a box of his things. He was director of the wound healing center, and in the box were medical lecture notes, kodak projector slides, and old textbooks. I started going through these things as a way to connect with him. I’d always had an interest in medicine, and I would’ve been a medical doctor if he hadn’t died, but his death turned me towards writing, towards grappling with grief on the page. It changed the arc of my life. These papers interested me for their contents, for the information they held, but they were also tinged with emotion. Because he was a wound-healing specialist, many of his papers were about wounds, and I learned that the best way to care for a wound is not to let it scab over (this can delay true healing) but to keep it open and wet. Learning the physical mechanisms of wound healing fascinated me, but it also struck me on an emotional level and changed how I approached my grief. In the past, when I talked about my grief, people told me, either directly or indirectly, that it was too much. They told me I needed to move on or, at the very least, keep my pain to myself. So, for a while, I tried to. Reading these old studies, though, made me realize that I needed to tend to my grief better, to keep myself open and vulnerable to it, to allow myself to be immersed in it. This book is the manifestation of that work; it is my wet wound.

Why did you choose the subtitle “an elegy in essays”?

The subtitle was a chance to guide readers a little more into what they were about to read. The words I chose were just as important as the words not chosen, mainly “memoir.” I didn’t want readers to enter this book thinking it would be a memoir because they’ll be sorely disappointed if those are their expectations. While there are memoiristic elements, readers will learn very little about me outside of one central experience. Rather, the work is done “in essays,” which examines this central subject, grief, from a myriad of different angles (some personal, yes, but others scientific, visual, archival, etc.) and wrestles with those approaches on the page. It was also important for me to note that these essays built towards something more central, that they were connected in their pursuit towards “an elegy.” Each essay, whether it follows the grieving patterns of orca whales or examines the history of pain in literature, is part of a central throughline, a verse in my song of mourning. Over the course of the book, this song teaches me how loss can lead to love.

How do you balance the heaviness of the subject matter in your writing?

How do you balance the heaviness of the subject matter in your writing?Part of the project of the book is refusing to turn away, to put down, this heavy subject, grief. I’d been told in my life that I needed to stop looking at it, but that was, for me, a harmful suggestion and one that not only separated me from my dad but also separated me from those around me. Grief is a painful experience, and this book refuses to mask that. I did not introduce levity or lightness because that was not true to my experience. Instead, I stayed with my grief, which in the end led me to the transcendent experience of real community and love. In refusing to get over it, I chose to get into it. This is not to say that this book simply sits in agony though—it moves through it. One of the ways I created this movement was through research, which added different dimensions to the experience. I don’t think of these additions as allowing readers to come up for air or escape the heaviness; rather, they can offer a horizontal movement, one that allows us to look at the thing we are diving into from a different angle. It grants new perspective, and because my father was interested in marine biology, was a scuba diver, and treated divers who surfaced too quickly, I think of grief like the deep sea: I haven’t found a bottom, but I have discovered, down here, a new, generative and curious world.

Was the inclusion of illustrations important to the work?

Yes! This was a non-negotiable for me in publishing the work. As I was going through my dad’s documents, I came across hundreds of medical illustrations, so part of the inclusion of these medical illustrations was tying my experience of going through my dad’s things to the reader’s experience of reading the book. There are seven illustrations total, all done by Kristina Alton M.D., who began many of them while she was studying the body in med school. The images are anatomically accurate, and several were genuinely study aids for her, but they are also beautiful. The intersection of science and art is something the book works to exist within, and these illustrations underscore that. The captions, instead of giving factual information about the images, introduce unanswerable questions. The images are a way to examine the unsayable. They puncture the narrative and force us to consider the subject in a different way. They’re another angle into grief, one that cannot be accomplished in text alone.

Who do you hope this book reaches?

One of the things that immediately comforted me after my dad’s death was reading. I read Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking shortly after he died and felt held. The book didn’t lessen my grief, but it made me feel less alone. That’s what I hope my book does for people. I know this book won’t be for everyone—it’s a hard book that refuses to look away. It’s a book saturated with pain and love. There was a man who once called my writing a “maudlin plea,” but at a reading, shortly after his father died, he came up to me to tell me how moved he was by my work, how seen he felt. The readers of this book will be ones who are open to feeling, who may be afraid of pain but embrace it anyway, who are grieving and need to be held.