Reviewed by Dane Beveridge

Reviewed by Dane Beveridge

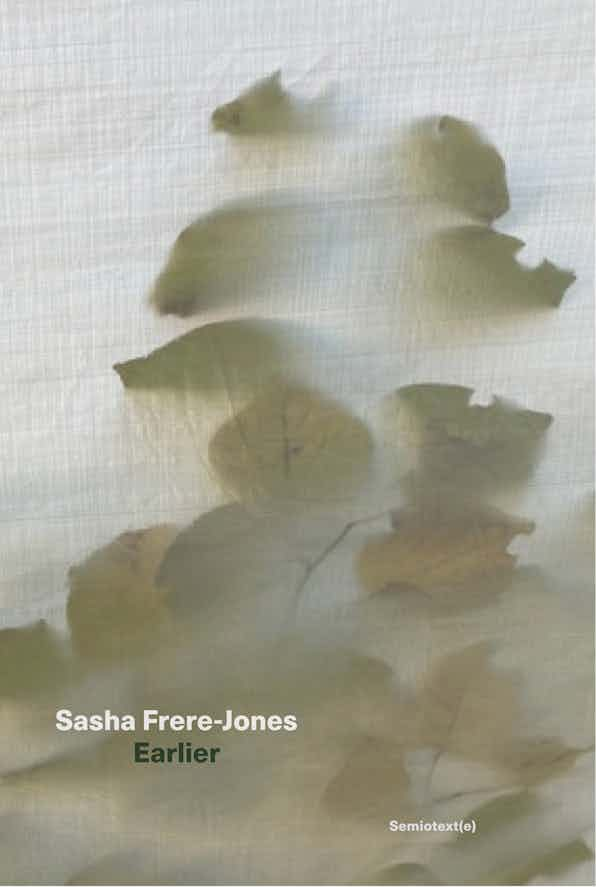

Earlier

By Sasha Frere-Jones

MIT Press (Semiotext(e))

$16.95, Paperback, ISBN: 9781635901962, October 2023

Dear Diary,

This is going to be my third and final attempt to write a “review” of Sasha Frere-Jones’s Earlier. If I write as if no one is going to see this, maybe I can achieve my aim.

It has been so bad that the second draft ended with a line: “But I don’t believe a word I have said,” which is probably the worst way to end a piece of writing. How selfish. How callous.

But I am going to have to construct here some artificial walls, so to speak, to make any sense of the book. For example, I do really think the way Sasha introduces himself on the second page is brilliantly cool:

The Frere family name is not French now but it was definitely French around 1066.

I begin as an American Jones with a Russian first name. The hyphen and the not-French French come later. . .

I also really wished that that was going to create a clearing in the critical discourse in which I could discuss the Situationists, among other Francophile souvenirs I’ve collected over the years. Afterall, “Greil Marcus, Lipstick Traces” is the last bit of language on the back cover. Possibility of a backdoor? But despite my efforts I could not find any such route into Earlier.

I can’t write a bad review, 1) because it is not a bad book and I’m sincerely interested, and 2) because the one bad review I have written in my life was so terribly received by my professor that I can’t stand the thought of disappointing him again. (It was also him who led me so gently through my “anarchist phase”, and so I’m permanently indebted.)

However, I find that in reflecting on the book my first and most salient feelings are tired. I cannot figure out what is at stake. It feels like a very straightforward memoir (despite its anti-chronological construction), and the most interesting episode is a botched opportunity to interview Prince. A non-event.

I’m disappointed, mostly with myself, because I know that Sasha is a maverick critic.

There’s a thesis of sorts that I am suspecting is the cause, or at least part of the cause of this dilemma:

The good old days are always just the old days.

And I agree to a certain extent. Nevertheless, by subverting the opportunity for nostalgia Sasha also sacrifices almost all of the proverbial wind in the sails of the form. And because it is not pitched as fiction, in the way of say Mike DeCapite’s Jacket Weather, or Eileen Myles’s Inferno, there’s no mystery. No myth-making. The quotidian NYC details don’t shimmer the way they do in these other two works, because here they only are what they are. I’m sure it was a conscious decision by Sasha, and I would be the first to admit of my own shortcomings in the approach to his book. But at this moment, our collective obsession with “auto-fiction”, a straight-up memoir has to have a significant edge. I think a lot of us want something akin to a dagger in the back — a thousand papercuts just won’t do. We are too important to die quietly.

“Take my picture.”

There’s another hint, dealing with an age/generation difference, which perhaps reinforces this thought. I’ll quote the whole chunk at length:

Positive Digital Natives (2021)

Wave 1 of computer people seem to want only the light in the box. If they aren’t hiding from view, they are at least avoiding attention. After that, Wave 2, the Myspace wave, is people who are happier in the box but willing to come out. The youngest generation, Wave 3, finds peers on the internet and also enjoys the flat world. This is somebody’s dream, I think, that the internet might foster wild and unchecked interactions that also happen in the world. This cohort isn’t hiding at all. They are tenants of two planes, optimists using a nihilist’s tool.

This passage is theoretical compared to the rest of the book. It causes me pause, not least of all because I can’t decide where I fit into this scheme. Neither does Sasha say where he considers himself in these waves. The “nihilist’s tool” clearly leads back to Marcus’s work, and suggests a level of engagement that could be quite fruitful. Why, for example, do we choose to live in a society constantly riddled with domestic terrorism and mass shootings? I am convicted to repent of my own soft-core rebellious folly.

All to say, I think this might be a Gen X thing, and I don’t know what to make of it. Again, likely my own shortcomings. I probably have not read enough of the books nor listened to enough of the music that situates Sasha’s text — especially the music, which is so central to it. And music is such a personal thing. To truly listen to your friend’s favorite album makes you a better friend.

I desperately want to avoid what Sasha warns of about a record store clerk named Albert:

Weak idealists make strong cynics.

The two monsters at the narrows on the odyssey of criticism. Never finished Critique of Cynical Reason, did I. . .

So, Diary — I think that’s it, though I can’t say I’m happy.

The last and most important thing to acknowledge is that this is a book created out of love, and that much is clear. The memory of Deborah is an illusory shadow throughout, from the dedication page to the final passage. If she was anything like my ex wife, she dealt with the grief from her godforsaken drunkard spouse with as much poise as humanly possible. Our living amends never stop, which — if you know, you know. For a few of us, writing is our very best action toward that end.

About the reviewer: Dane Beveridge writes in Los Angeles where everything is concrete. In the Global War on Terrorism he served aboard a fast-attack submarine in the Pacific Fleet. Find his work at www.dbeveridge.com.