Reviewed by Amy Penne

Reviewed by Amy Penne

The Daughter of Man

by L.J. Sysko

University of Arkansas Press

April 2023, 109 pp, ISBN: 978-1-68226-230-6, Paperback

Midway through The Daughter of Man (University of Arkansas Press, 2023), L.J. Sysko’s formidable feminist speaker addresses an open mic attendee in “To the hypothetical hostile man in the audience” with “I am not/ the unwitting galleon or biddable pretender you imagine though/ my cannons may impress & I was taught to speak fluently the language of my oppressor…” This collection’s feisty speaker, worldly and wise, takes on hypothetical hostilities, traumatic recollections and encounters, as well as the delights of a woman’s aging body in this enchanting first full-length collection of poems.

Finalist for the 2023 Miller Williams Poetry Prize, selected by Patricia Smith, Sysko’s The Daughter of Man absorbs the reader into a wide array of ekphrastic works interspersed with contemporary sonnets, lyric bursts, and concrete poems. Sysko’s collection invites the reader into her evolutionary worlds, inhabited by the section titles: the Maiden, the Warrior, the Queen, the Maven, and the Crone. Each section, as poet Patricia Smith notes in her editor’s preface, “is gleefully unapologetic, upending the familiar and blasting it with motion, heat, and consequence.” The book is a tailored and careful collection of wild poetry. Poetry that unnerves the reader and then turns around and makes her laugh.

Sysko’s poetics are enviable. I’m jealous of her seemingly effortless ability to float between the particular and the universal with ease. In “tablescape” from the Warrior section, the poet compares women to “hares pears plums pomegranates women/ we’re portraiture’s chorus line/ having kicked our legs into one/ busby berkeley bloom/ and opened our necks/ to composition’s beheading.” This striking image of woman as composition, as an artform compared to a still life basket of fruit juxtaposed to a 1930’s Busby Berkeley composition is as musical as it is imagistic. This brilliant poem ferries the reader in between two of Sysko’s most robust ekphrastic poems in the collection, both based on the paintings of the 17th-century Italian Baroque master, Artemisia Gentileschi. “Tablescape,” juxtaposes one ekphrastic musing about Gentileschi’s Self Portrait As the Allegory of Painting (La Pittura) against one of the artist’s most famous paintings, Judith Beheading Holofernes, and creates the perfect triptych detailing woman on display, woman taking agency, and woman “rooted on the edge” of what is, and is not, acceptable behavior. Sysko conjures art and artists in this cauldron of poetic forms while honoring the heroine’s developmental journey from Maiden to Crone.

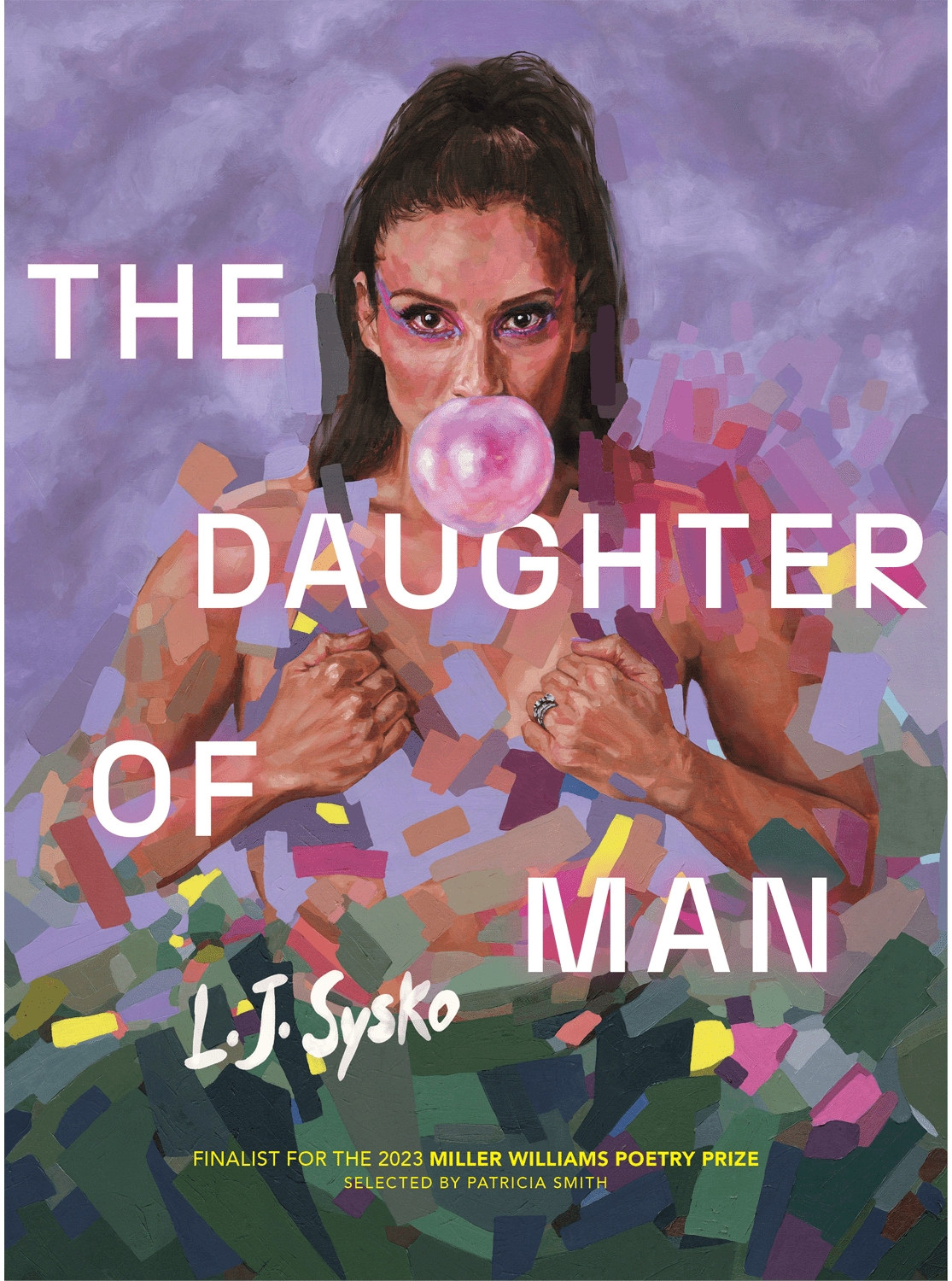

In a virtual reading for the South Florida Poetry Journal, Sysko discusses the cover art, which for this collection, is vital to the project as a whole. Illustrated by Chloe McEldowney, the image is of Sysko herself, with a pink bubble-gum bubble obstructing part of her face, and her strong hands tugging at her chest as if to open the cavity forcing color and collage onto the cover. Sysko notes in that reading and elsewhere in interviews on YouTube that the cover and title of the work are a comment on René Magritte’s Son of Man. Her collection, situated as it is among homecoming queens, The Price is Right, Plinko, and Dolly Parton, dives into a conversation with Magritte’s work from a female perspective. Magritte’s commentary on the overshadowed everyman is, in Sysko’s reworking through the heroine’s journey, reconfigured for a 21st century reader but it doesn’t lose the thread of the Belgian artist’s post-war surrealist critique of the disembodied individual. Sysko’s collection embodies several personae working out their place in the sweeping history of art but also in the particular space of women’s lived experiences in our time and space.

In “Self-Portrait with Bubble Gum,” the speaker refracts the cover art’s “face-obscuring bubble lips/ pursed into an O of Greek choral epiphanic echo.” The speaker is “banal danger in a full face of makeup I’m half a sour citrus dolloped with cottage cheese and maraschino-topped Sweet ‘n Low strapped in sidecar.” Sysko brilliantly weaves rhyme and meter into these poems, tumbling alliterative sounds throughout just like the chips falling through Plinko pegs.

Sysko’s speaker in “Self-Portrait as Molly Pitcher,” dons the Revolutionary War version of Rosie the Riveter. A common reference for women who served in various roles in the war, Sysko puts Pitcher in context with Betsy Ross: “Betsy Ross, you know her? As though hookers working the same corner are necessarily friends? I never met her until they locked us both up in an inset box. There in the basement of a history textbook page, we didn’t even speak.” Sysko’s self-portrait moves these 18th-century women from the “inset box” of historical textbooks to the evolutionary spirit of contemporary feminism and situates her speakers, and us, as onlookers but also as agents capable of changing the narrative.

In one of my favorite pieces in the collection, “Trompe L’Oeil,” Sysko integrates the ongoing bubble-gum motif as well as another Magritte reference, this it is his Treachery of Images, or “This is not a pipe.” In a contentious conversation with a former teacher, “Mrs. K,” Sysko’s narrator confronts her memories:

I’m back–grabbing you by the Peter Pan collar to chew gum in your class, drop your hall pass in the toilet, and eat your breakfast for lunch. I won’t recover my manners, no, they’re pinned up there under the postcards, ribboned fast to a bulletin board between lion and lamb. You sat the girls in the back of the class and taught math to the front. And I guess I have the option of being less mad, my upset’s been tipping on the precipice forever, like a Medici cherub poised for a rotunda-fall.

That’s the image that poked my jealous g-spot. It doesn’t take much to give me writer’s envy. But Sysko’s Medici cherub put me over the edge. It’s worth a trip over to YouTube (this poem is towards the end) to watch her read this poem aloud to see her unfurling her “fingers 1-2-3” as she jabs a defiant middle finger to Mrs. K.

L.J. Sysko’s Daughter of Man is an exquisite dance in which form, function, image, and metaphor shape a discernible allegory of embodied personae. And while these speakers delight the reader with a variety of references to pop culture, they also serve as reminders of our shared historical narratives, ones we cannot let slip from our cultural memories. In “Kristallnacht,” Sysko notes that “female Jews who did not have ‘typically Jewish’ given names were forced to add ‘Sara’ to official identification cards.” The body of the poem reverberates the beauty and tragedy of “Sara to Sara to Sara/ and their/ blazing/ vanishing/ point.” L.J. Sysko weaves together Saras’ stories, Gentileschi’s heroines, bubble-gum popping teens, and sagacious crones in a masterful collection.

About the reviewer: Amy Penne is a writer and Professor of English at Parkland College. She shares her thoughts and musing around the intersections of creative writing, poetry, and life in her blog The Pensive Penne. Amy’s essays, reviews, and poems have been included in Tupelo Quarterly, Minerva Rising, and Brain Child, among others, and she has a new essay called Exit 212: A Haibun Comfort Food Essay forthcoming in Midwest Writing Center’s upcoming anthology These Interesting Times: Surviving 2020 in the QC. You can follow Amy on Instagram (@pensivepenne), Facebook (@amy.penne), and Twitter (@thepensivepenne).