Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

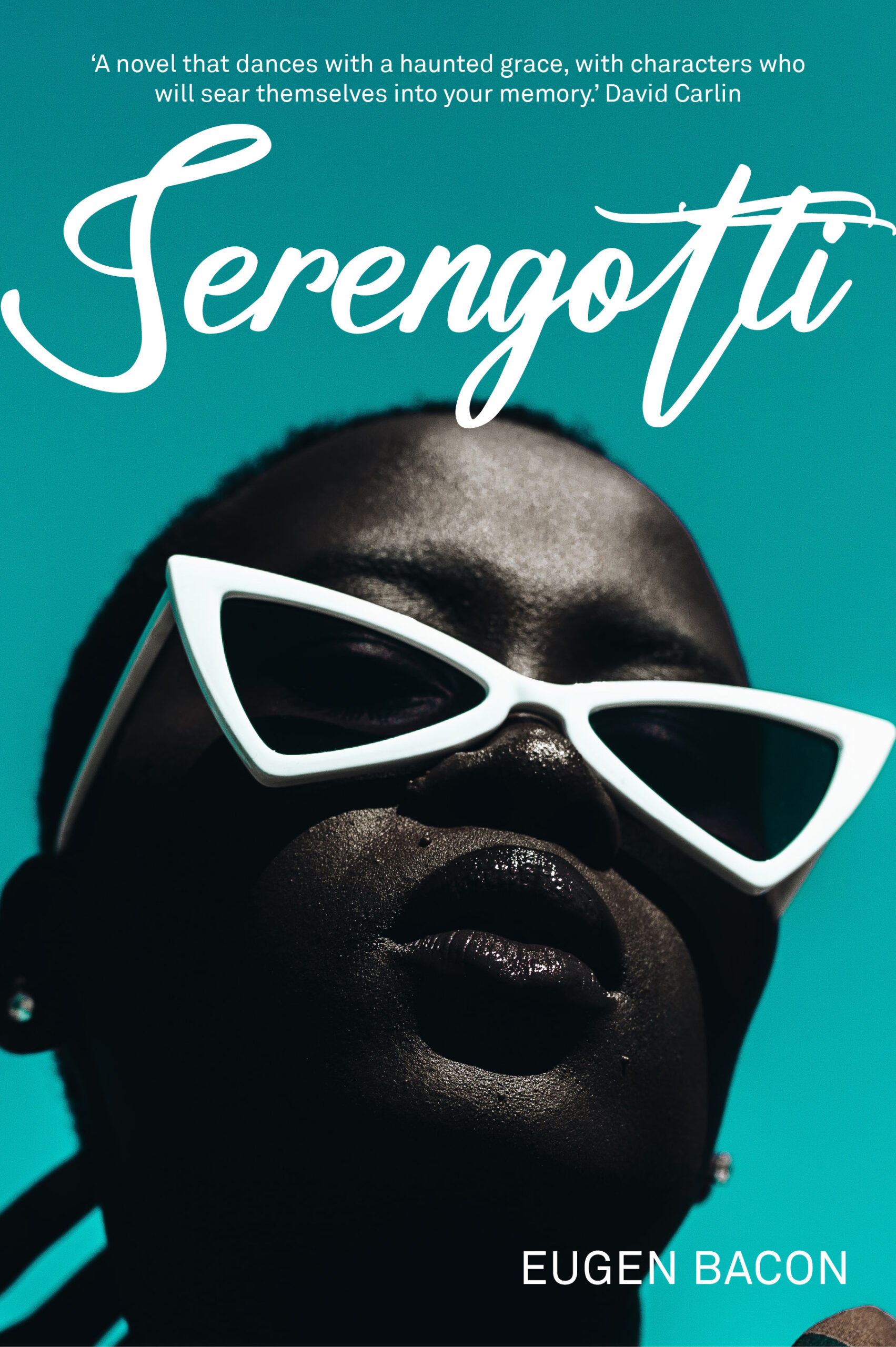

Serengotti

By Eugen Bacon

Transit Lounge

ISBN: 9780645565362, Paperback, 288pp, Aug 2023

Eugen Bacon has become known for her award-winning fantasy and science fiction. While Serengotti is neither fantasy or science fiction, set as it is in present day Australia, the book has a magic-realism quality, due in part to its slightly hallucinatory nature and in part to the dream-like perspective of its protagonist and main narrator Ch’anzu. Ch’anzu is a gender fluid, talented computer programmer who opens the book by quitting hir (pronouns zie/hir) contract job of five years at Multicorp. It’s a taut opening, charged with racism, sexism and a condescension that Ch’anzu doesn’t endure easily. The day continues to deteriorate as Ch’anzu heads to a local bar to get drunk and then goes home to find her wife Scarlet In flagrante delicto with a flashy, mohawked guy. Right from the start this fast-paced and engaging novel sets up a narrative where external action jostles against a self-reflexive second person narration. This fragmentation of the self creates powerful tension, that is rooted in Ch’anzu’s physicality as zie swims, walks, moves through the world:

You live in the present, but it’s the past. You’re wrapped in colours, a riot of table, ribbons swirling inside your head. You wish your mind was a puppy’s — a gleeful yap-yap. But all you have are mistakes, ghosts act give and give. No returns. (38)

Ch’anzu moves to Wagga Wagga to design a computer app for a community living in a 50 hectare, self-contained village designed to house African refugees, many traumatised and some hostile to Ch’anzu as newcomer. That community is the Serengotti of the title. Bacon draws on her IT background and extensive world building skills to create an immersive space “decorated in ochre, charcoal and henna, heavy wooden doors inscribed with Afrocentric art of buffalo skulls, ebony gods and goddesses, masks, mothers, creation and spirits”, complete with alternative medical treatments, African music, a ‘black soul’ restaurant, hand-to-hand combat lessons, and traditional foods and drinks. The theme park quality of the place is both seductive and repellant to Ch’anzu who can’t help but become a bit obsessed with Serengotti and its inhabitants, even as they challenge hir sense of self:

DUSK. You approach the stone-walled chapel crucifying its black Jesus, take the frangipani trail, white lights neatly arrayed behind the petals. It’s a road to nirvana. (109)

The other voice in Serengotti is Ch’anzu’s twin brother Tex. In his own words, he doesn’t say much, but his italicised segments shed light on Ch’anzu and the dysfunctional and sometimes violent nature of their relationship. Tex opens and closes the book and his voice is woven in small segments throughout, an unpredictable and malevolent but also needy voice, born out of loss and pain:

But before she turned her head, I caught a hint of softness. Long after she lifted her hand, her touch still burned my shoulder, drew me to her skirt, to her soft chocolate and powder smell. My tears escaped, and I quietly wept for us all. (192)

Other characters include Ch’anzu’s charming Aunt Maé whose earthy conversations with Ch’anzu move easily between past and present. There is also Valerie, Ch’anzu’s new boss who seems to have specifically summoned Ch’anzu: “Maybe I know how to fish out the gaspers. Chuck them back into the right waters.” and Ariana, the elusive and beautiful young woman with a voice like music who Ch’anzu meets at Serengotti. These characters are richly and sometimes humorously depicted but because of the dreamlike way in which we see them through Ch’anzu’s fragmented perspective, they almost appear, as does Tex, like alter-egos or personalities rather than like separate beings.

At one point Ch’anzu talks about being “alive in an erasure poem”, and the whole book has a poetic quality to it, with language that is condensed and evocative:

Perhaps normality is the chug and hum of a tram in the belly of winter as it staggers between stops, punctured with arrows of human-tinged breeze: perfumed, sweat-infused or scent free. It’s as if the curl of fading lights as a night car sweeps round a bend, casting a passing spotlight on a twosome just met on a sexting app with a ‘nearest finder’, now entwined under a vigilant moon for a kiss that could be the start of something or the end of it? (41)

Words trail down the page at the end of some of the chapters, are metaphoric and often dreamy, and in Serengotti a new language is introduced, created from a mixture of Swahili, Bantu and made-up language, complete with its own glossary at the end. These words are onomatopoetic, with a rhythmic quality that conveys more than one meaning, like “Ali, pampula” or “mksha”, an all-night feast and mourning session which Ch’anzu attends after one of the mysterious murders that begins to plague Serengotti. Ch’anzu’s narrative arc drives the novel forward as the mystery deepens and zie begins to work through her own faltering mental state. The traumas and ghosts of Ch’anzu’s past are woven through the book, and Ch’anzu simultaneously works through these traumas while developing the app. Serengotti is a strange and beautifully-written novel which takes the reader into new places, exploring shame, trauma, displacement, and desire in a way that is both disconcerting and beautiful. The blurring of boundaries, binaries, settings and linguistic constructs make Serengotti an exciting and vibrant read.