Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

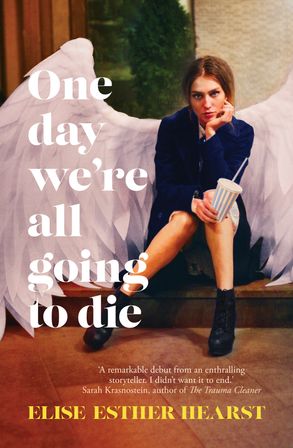

One Day We’re All Going to Die

by Elise Esther Hearst

HarperCollins

Aug 2023, ISBN: 9781867251279, 320 pages, Paperback

Elise Esther Hearst’s One Day We’re All Going to Die is a bold and ambitious novel that does not read like a debut. That’s probably because Hearst is not a debut writer. She has several plays to her name, including this year’s A Very Jewish Christmas Carol, premiering at the Melbourne Theatre Company in November and a modern version of Yentl, about to enter a second run. Naomi, the protagonist of One Day We’re All Going to Die, is a 27 year old woman working at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in Melbourne which feels like a combination of St Kilda’s Jewish Museum of Australia and the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York. I know the latter enough to recognise the mixture of intense history focused on the pain of the Holocaust combined with a kind of kitschy focus on Jewish culture which Hearst captures well:

The front of the building housed a permanent gallery documenting Jewish life and ritual, and a large contemporary extension at the back held temporary exhibitions that changed biannually. The home’s original kitchen displayed traditional Jewish foods amid warm wooden panelling and Do Not Touch signs: petrified matzah balls floating in plastic soup, a papier mache challah, paint-chipped wooden dates and pomegranates. (6)

Naomi enjoys working at the museum, showing a methodical reverence with artefacts like the 230 year Haggadah from Poland, or researching and labelling museum items: “crafting a narrative, giving names to things that had been nameless.” In many ways Naomi is a typical young woman exploring her sexuality and attempting to differentiate herself from her family, the shadow of inherited trauma hangs over her in unspoken ways. Her grandmother Cookie is a Holocaust survivor whose parents and sisters were killed at Chełmno, one of the Nazi’s first extermination camps. Her father’s brother died in a displaced persons camp:

Separation aside, my parents experienced similar childhoods of Australian sunshine and dark break, and darker nights where, once in bed, grown-ups would speak in heavy sweated tongues about the things they didn’t want their children to know. (23)

Naomi and her sister, with whom she has a dysfunctional relationship, are raised in a “consciously Jewish environment” with artsy, liberal parents whose weight of expectation is another burden that Naomi carries. Naomi’s mother is continually pressuring Naomi to find a Jewish boyfriend, to make more of her life, and to take more care of herself, and her subsequent disappointment is obvious. Hearst has been compared to Sally Rooney and there are similarities in character between Naomi and Normal People’s Marianne, in the way Naomi allows herself to be passively carried along into inappropriate relationships and situations that cause her pain, or as her mother puts it, letting life tumble about her “like an upturned bedroom.”

Hearst’s writing is deeply engaging, full of rich detail and the link between Naomi’s low esteem and the trauma she has buried subtly handled with humour and a rapid progression that makes for a fast and emotionally satisfying read. Cookie is a particularly enjoyable character, combining deep sorrow with a blunt black humour that is sometimes laugh-out loud funny. Naomi’s relationship with her grandmother is very tender, with all sorts of cues, from the tender way Naomi strokes her grandmother’s hand or rubs her feet to the way she continues to think about the way her grandmother might respond to a situation even when Cookie is not there. Cookie’s characterisation is is immediately recognisable with a deliciously quirky quality that reminds me of my own Jewish grandmother and her propensity to tell dirty jokes at inappropriate times:

‘Your mother was murdered and now she’s dead, darling. That’s what I said to her. Exactly.’

My grandmother’s mouth, like a malformed wire hanger, bent from a grimace into a smirk. I watched her add two Equals to her coffee, stirring haphazardly with the spoon in her better hand. Coffee mud gushed over the sides onto the saucer.

It is Naomi though whose coming-of-age first-person narration drives the story through her anxiety to separate from her family coupled with a growing realisation that happiness and healing can only happen through connection. This is a connection with her own family and what she has inherited, good and bad, but also to the notion of what it means to be a storyteller as she moves from passive participant to active creator in her own life:

I realised in this moment that I’d never really thought about whether it did matter to me or not. I’d only thought about what mattered to other people. I looked at Cookie and thought: your blood is in my blood and therefore your blood will be in my children’s blood and so on and so forth, but we are all going to die. You will die. Mum will die. I will die. My children and my grandchildren and my great-grandchildren will die. So all there is is blood and death and the stories we tell ourselves and each other. (198-99)

Deceptively easy to read, One day we’re all going to die is a rich, complex book that encompasses family and connection, friendships, privilege, survival in the face of inherited trauma, Judaism, culture, modern life, and the healing power of creativity. If that seems like a lot, it doesn’t feel like it. Hearst handles it all with ease, and the book is a light-hearted joy.