Interview by Marcene Gandolfo

Interview by Marcene Gandolfo

How did your collection evolve? Can you say something about your composition process? What role did this process play in the construction of your book and ordering of the collection.

I try to write for at least an hour every morning, unless I’m taking a very deliberate break from the process (like taking a year off to let the well refill, so to speak). This book grew out of my daily process. Initially I was just trying some new craft exercises to stretch as a writer, and then I began to observe the thematic threads and obsessions that were developing and to write more intentionally into those spaces. When I write a book, I usually start with a lot of unformed material that starts to coalesce around poem-like gestures (a craft move, a particular idea, a scene). Toward the end of the book process, the partitions or divisions between poems become more clear, and I start to see how the material is cohering into individual poems or sections. That’s how this book developed for me. I also tend to like a lot of variety in forms, tones, and modes in a book. When I wrote this book, breaking it into more sections helped me pivot more easily between all the shifts—there’s a couple series of poems and then a mix of other lyrics, and some are more dream-like and some are more conversational. At one time I think I had the book broken into three sections, but I received good feedback from early readers to break the poem series out into their own sections, and I

think that helps the reader more fully digest each section and its arc. Same with order, which was a balance of tracking the large arcs of the book—the speaker accepting their ace identity, coming to terms with the figure of the mother—and splitting things up enough for the reader to parse everything. Especially with longer poems like “Crown of Screws” and prose poems throughout the book, it was important to give readers breaks after the denser poems, and so the order and the structure were ways of managing the reader’s attention as much as thinking about the crisis of each section. A lot of the order was discovered by taping the poems to my walls and organizing them in sections, as well as taking down what I liked but didn’t fit. There was also something nicely organic about that process—poems sometimes fell down on their own, or cats pulled them down to chew on them, and whatever I didn’t miss could be left down. That meant I also had my greatest clarity about the book and its concerns near the very end of the process, when all the poems were tangible and gathered in one place so that I could grasp the complete arc and concerns of the book all at once. Once I got the order locked in, I got some great feedback and rearranged a bit, but really most of the collection’s order was shaped through a process of analysis and instinct.

So much of the lyric centers on the “I” in relation to “other.” In your “Aroace Girl” poems, what features make the “I” distinct? In my reading, these poems express a strong yearning for the other, or the beloved. How do you characterize this yearning?

This book was really an attempt to find a lyric or lyricism that could hold my experiences as an asexual aromantic person—someone who doesn’t really experience sexual attraction or romantic attraction. So a lot of the poems are built around the figure of “Aroace Girl,” a speaker who articulates what it means to not want in the same ways as other people and to experience a kind of alternative erotics in kindship with the ecological world and in platonic relationships. It was important to me to provide the explicit context and labelling that this is an ace aro speaker who’s not interested in sex or romance. And sometimes that speaker addresses other figures with platonic or queerplatonic intimacy. I think many of my poems are love letters—to friends, to myself, to people throughout my life, to an imagined amalgamation of all of the above. I think there’s a yearning in this book to be close to people and to be understood without being reduced to a sexual object to be consumed. To be in a wholly safe space where the body is not an object of unwanted attention for someone else’s pleasure and power. A world mediated through friendship, trust, and kinship of the mind and self without being about sexual or romantic attraction. I think the speaker is as much leaning toward the persona or figure of the trusted other as leaning away from people who assume the speaker exists for their own attention.

The “Omphalos” section depicts the speaker’s matrilinear history. Could you comment on the significance of this history and the mother-daughter relationship?

I had the wonderful opportunity to read recently with fellow CSU alum Claire Boyles, and we had a wonderful discussion about what it means to create or open new spaces within a family. The speaker in the “Omphalos” poems and elsewhere in the collection has been given a lot of family stories that directly and indirectly teach about power dynamics, gender and sexuality expectations, and wounds. A lot of the poems circle these forms of wounding indirectly while trying to create new spaces going forward: for queerness, for kindness, for new narratives. The figure of the mother in these poems acts as a kind of intermediary figure—someone who both passes on the old narratives and who teaches the speaker to create a new space and a new home. By the end of the book, I think both the speaker and the figure of the mother in these poems are able to make a break from previous traditions, including those that have no room for the speaker’s queerness.

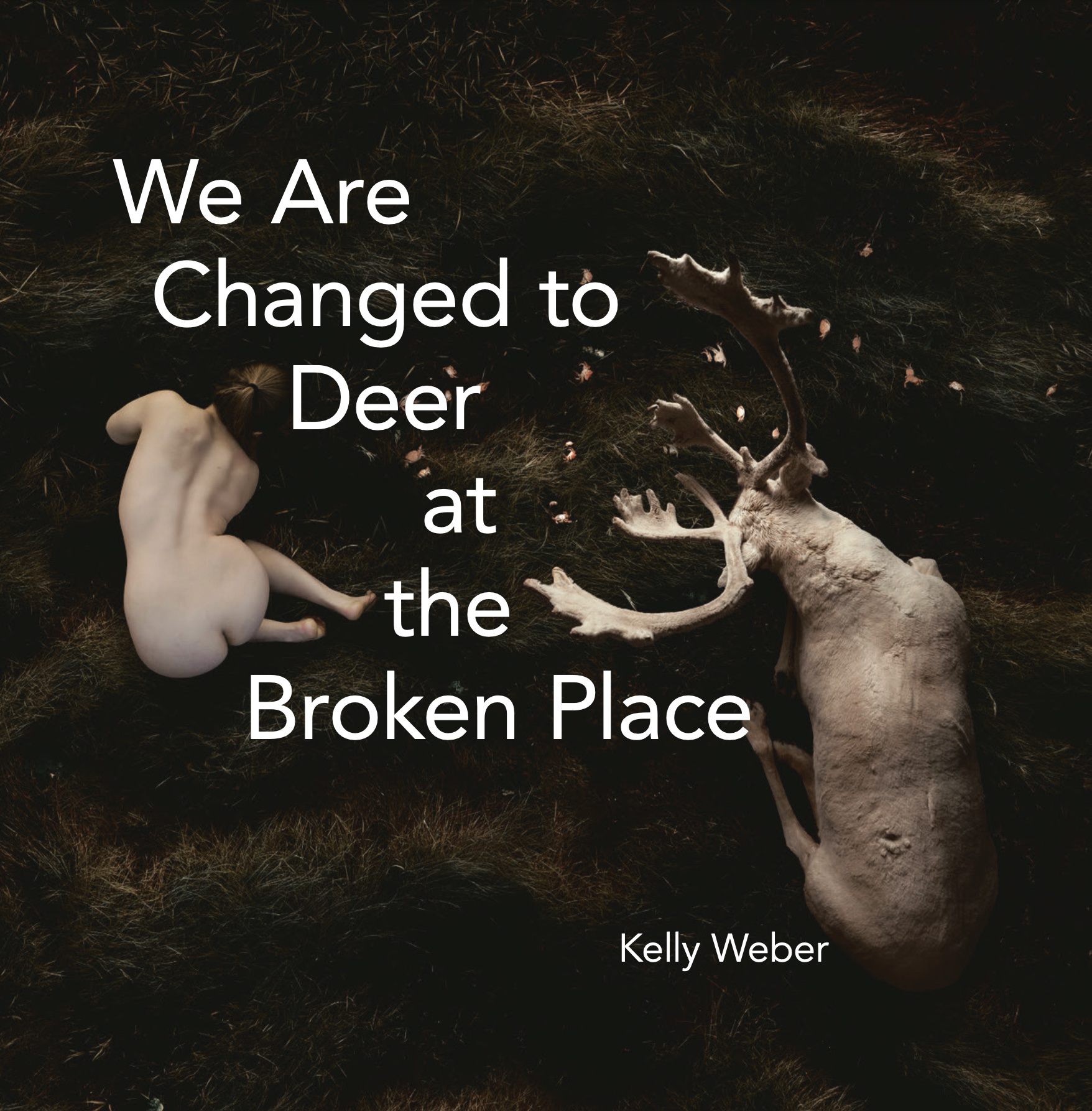

I was particularly struck with the mythic resonances in the poem “Actaeon.” How does your speaker identify with Artemis? How does the poem address the male gaze? And how does your speaker set Actaeon “on a new path”?

One reason I was struck by the story of Artemis and Actaeon is that Actaeon is the one who is transformed as a result of his transgression, instead of Artemis fleeing and transforming to escape him. Instead of losing her own bodily autonomy in order to escape harm and the male gaze, she turns the gaze back on Actaeon and transforms him. In my poem, Actaeon becomes a symbol of patriarchy (including internalized patriarchy), and the transformation partly explores the desire for a radical transformation of the patriarchy and toxic masculinity into something new and better. A kind of obliteration. I think Artemis is also a figure who resonates with a lot of the ace and aro community, so in this poem, she resists having her body and her queerness reduced by the male gaze.

In mythology, the deer, stag, or doe is often a messenger that traverses conscious and unconscious realms. I’m interested in this recurring image of the animal throughout the collection. Could you say a few words about the prevalence of this image?

I think the deer serves a lot of roles in the book. Partly the deer speaks to the myth of Artemis and Actaeon. Partly it speaks to toxic gendered narratives I received growing up and being taught the way cishet men were expected to “pursue” me, like a deer being pursued. And part of it speaks to the rural areas I grew up in with lots of deer, the hunting culture around those deer and how enmeshed that culture was with a certain kind of toxic masculinity. The deer in the book are simultaneously vulnerable and dangerous, just like very real wild deer. I associate deer movements and features with delicacy, but they can easily defend themselves. I think that paradoxical tension works its way into the book. I also remember a lot of wild stags chasing does through the woods behind my home when I was growing up, to the point that they would scrape their antlers against the trunks of trees and strip off all this bark. So I think there’s paradoxically an element of the deer—their sexual impulses and mating urges—that feels radically different from the speaker’s own embodied way of being in the world, and I think the book explores all of these different tensions.

What is next for you? Are you engaged in a new project? If so, would you like to tell us about it?

My second book, You Bury the Birds in My Pelvis, is forthcoming from Omnidawn Press this fall! That book explores more of the nuances of queerplatonic intimacy as well as being genderqueer. I’m excited and hope that opens other conversations about what it’s like to move through the world in an asexual aromantic body!

About the interviewer: Marcene Gandolfo is a poet, writer, editor, and educator. Her debut book, Angles of Departure (Cherry Grove Collections, January 2014), won Foreword Reviews’ Silver Award in Poetry. Marcene’s poems have been published widely in literary journals, including Poet Lore, Bellingham Review, and December Magazine. She has taught writing and literature at various colleges in northern California.