Reviewed by Elvis Alves

Reviewed by Elvis Alves

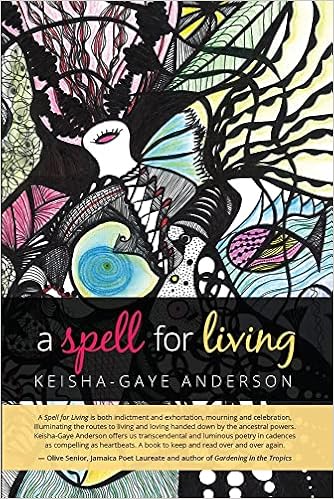

A Spell for Living

by Keisha-Gaye Anderson

June 2021, Paperback, 76 pages, ISBN-13: 978-1736465509

The writing in Keisha-Gaye Anderson’s A Spell For Living affirms life in that it encourages us to look within and beyond what is deemed reality in order to enjoy the present and take ownership of ourselves. The book is multifaceted in its construction. Its poetry is complemented by original artwork by the artist and contains voice recordings of Anderson reading her poetry (The ebook is free at keishagaye.ink and the audio poems are on SoundCloud). Spirituality is at the core of Anderson’s work. In it, she talks about God, the self, and the universe in one breath. These, and more, are attributes that shine light on spirituality but do not define it in totality. Anderson’s poetry leads to this point, that of knowing yet not knowing while searching for meaning.

The push to cross manufactured borderlines, physical, mental, and otherwise, is impressed upon in Anderson’s work. To do this, she employs poignant and open-ended questions, like those asked by the philosopher, religionist, or seeker of wisdom: “When cities are erected / everywhere / what of us will be left?” (“The Purge”) and “Why not move something? / Why not change the melody?” (“For Freddy Gray and All Those Murdered by State Violence”). Additionally, Anderson’s word choice draws you into her poetry, a light leading you in the dark. She wants you to question the validity of what you have been told and look beyond this—and beyond constructions of time, and even conception, to locate a secure sense of self. Here’s a stanza from “Fly”:

I want to fly

outside of predation

where time is a memory

and the fire

that moves these legs forward is itself

just for the sake of it

no longer needing to

push a horse

of bone and amnesia

The journey is encouraged and aided by a motherly figure that shows up in Anderson’s work. She is dreamlike and is associated with water. Water points to her power. Here are two stanzas from “We Talawah,” a term whose origin lies in Jamaican patois and means tall and strong, or having strength:

Meeting guardian

caciques in the land of Mami’s

sweet waterAnd she organize us all

by heart,

not by skin

Relationship with this figure and the divine that she represents is relationship with the self.

The title poem has a woman entering a church not for worship of any gods but of self. One can read this poem as a deconstructive critique of institutionalized religion but at its core is the celebration of what it means to be a true self that walks with confidence in the world:

…storm the church

and use the holy water

to douse your head

kick over the lectern

and slide between

the pews

write the names

of all your lovers…

The poem is not sacrilegious in that it is a celebration, a notice that can be buried in societies that prioritize wealth, fame, and other ephemeral goals above the recognition of a shared humanity. In the poem “Dis/Ease” while seeing a mentally ill homeless person, Anderson thinks of his mother:

someone pushed him

through her flesh

into the world

didn’t sit on his neck

loved him long enough

for him to not die

Anderson wonders what happened between birth and now to cause the man to be in the situation that he is currently in. We can assume societal, personal, and other forces as culprit. Anderson sees the man due to a watchfulness apparent in the construction of the poems in the collection.

The art of seeing is also evident in the artwork in the book. Anderson’s drawings have a colorful quality that draws you to them. They are done with colored pens and are untitled. Some contain circles that resemble eyes. These seem to say that they are watching you as much as you are watching them. Other drawings remind one of the insides of cells, think high school biology class. Is Anderson saying something about life here? The artwork’s beauty, and there are many aspects to this, is that the drawings allow you to make your own meaning while you are searching for meaning. This notion of agency is not removed from the poetry of the collection; indeed it is all a spiritual experience.

About the reviewer: Elvis Alves is the author of the poetry collections Ota Benga (Mahaicony Books, 2017), Bitter Melon (Mahaicony Books, 2013) and Blackfish (Salmon Poetry, 2022). Find out more at www.poemsbyelvis.blogspot.com or grab a copy of Blackfish here: https://www.salmonpoetry.com/details.php?ID=559&a=356