Reviewed by Ravi Shanker N

Reviewed by Ravi Shanker N

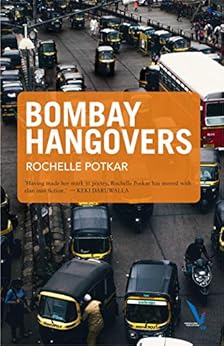

Bombay Hangovers

by Rochelle Potkar

Vishwakarma Publications

216 pages [Paperback], Feb 2021, ISBN-13: 978-8195012633

Italo Calvino, the famed Italian writer, says in his ‘Invisible cities’: “Every time I describe a city I am saying something about Venice. Memory’s images, once they are fixed in words, are erased. Perhaps I am afraid of losing Venice all at once if I speak of it. Or, perhaps, speaking of other cities, I have already lost it, little by little.” This predicament is visible in the writings of many authors who speak of their own cities though residing in other cities. Each city has that quality to make a writer succumb to its own charms while being nostalgic about another.

Not so with Rochelle Potkar, who though from Goa, has spent much of her time in Bombay/Mumbai. The very usage of the name Bombay by her betrays a long-term association with the city now named Mumbai. This is another nostalgic trip of the kind Calvino speaks of – being nostalgic for an older city named differently which though is now known by a new name. Thus, in her collection of stories ‘Bombay Hangovers’, Rochelle exhibits this nostalgia of sorts. She is still drunk by that old cocktail of a city named Bombay.

A city lives not in its massive skyscrapers or spanking new malls and cars, but on its underbelly. That’s the constant that every living city has. Once the underbelly is stabbed, the entrails slip out in wriggly masses of intestine and feces. The city dies. Rochelle’s Bombay is thus described in many ways in these stories where the characters merely play a heroic role in its preservation though unsuccessfully. Her collection is in itself an act of preservation.

Rochelle’s stories signify a city that is no more. Even as we go through the stories, we see the city slowly dying before our eyes.

Thus, in one of the most historical of stories, Rochelle speaks of a mill worker whose ambition was to become a Supervisor, but who becomes one of the victims of the Textile Mills strike, an event that changed the geography of Bombay forever. Before the strike, “The mill was family. Spindles ran at 16000 ribbons per minute. The clickety clackety of the ginning and weaving machines and power looms” filled the air.

Hundreds of Textile Mills were closed after the leader of the strike Datta Samanth was shot dead, with 17 bullets to his head. The workers turned to other menial jobs. Many families perished. The prime lands on which the Mills stood were bought by land sharks who made a kill by building Malls etc. The ambitious Kailas, the protagonist, becomes a security guard in a Mall built on the land occupied by the same Mill in which he worked and dies an inconsequential death narrated simply as “In another 20 years, Kailas retired in the same role as of a security guard from Currimboy’s Cupola. He had a major heart attack five days after that and died at 61.”

Is it the death of a person that Rochelle is describing thus? No, she is talking of the death of a city. Simply titled ‘Fabric’, it gives a full measure of a city’s aspirations through the medium of the fabric worn. Meticulously researched, the story has a running history of fabrics, brands, and tailors built into it.

This meticulous nature of her research into each story marks her out from other writers. This is again evident in another beautiful story where a Parsi youth is obsessed with creating his own brand of perfume (Parfum). Rochelle goes into a heady mixture of the scents and perfumes employed. She even has a lab where the protagonist works to manufacture that one perfume that can be his own. Finally, instead of his wife, he finds solace in the arms of a maid whose function is merely to be like a springboard of scents. He sees his city in a new light. “He has forgotten it had existed above his worktable. There was a city outside that window. “

In ‘The Arithmetic of Breasts’, the subject of ‘Topology’ is examined in all its facets, Rochelle is once again meticulous in her research work. “He liked shapes anywhere. Oh! Didn’t he? The properties of objects are preserved through continuous deformation by twisting, bending, stretching, but not tearing, where a circle could be an ellipse, a sphere an ellipsoid. Topology – the study of knots.” What happens is that when Narain and his research assistant had a coffee or smoke, “they would talk about the shape that almost ruled the world – the female shape.” Narain marries a woman with well-shaped breasts who ironically has breast cancer later and one of her breasts had to be removed. “For years, she had almost forgotten about them. They were there, beautiful, well supported – silent partners of her anatomy in the crime of trying to live a good, successful life.” The topology of the female shape becomes an allegory on the city front packed with well-shaped skyscrapers. Narain almost forgets the way he used to salivate over her beasts “now excavated like a mine, the earth of bruise-skin still being where it was, and the same.” “The topology of everything – that no matter how many things changed, even with tearing well-etched memory and its seasons and feelings, their shape would always remain the same. Intact. Retraceable..” It is, nevertheless, an allegory on the topology of the city itself.

In her exploration of the city, all kinds of human labor come alive in the stories, be it that of lovers meeting in a cheap hotel room, maids, or of a dhoban whose son is arrested for rape and later killed. There is no remorse as “some stains would never go away, with any ointment, malham or lape.” There is a maid named Satyavati who tells her Maalkin “how she dreamt of her beloved each time she was forced upon by various men” while her maalkin had a number of affairs, her own “way of equaling the scores, besides having a secret harem of male lovers at my disposal.”

In Euphoria, two women, Fathima and Naina, the most unlikely of friends meet through their love of snacks served in a roadside stall. Muthu, the vendor, slowly rises to become the owner of a restaurant in a Mall. Fatima watches the city flowing by and comments, “ This city that allowed me to be me. Us to be us.” She watches “ the workforce of Bombay make their way home – pedestrians worming through, bikers and two-wheelers snaking against cars, and the cars waylaid by big, private or state transport buses.”

‘The metamorphosis of Joe Pereira’ is the shortest story that talks about Joe and his ancestral plot which is invaded at will by coconut gatherers. One day, he picks up the courage to throw one of the coconuts at a gatherer. He is pushed to the ground, but he is happy. “The first showers come down and drenched as he is, he – Joe Emmanuel Pereira – has taken action for the first time in his life.” This is an allegory of how the city heartlessly strides over the weak. We know that when Joe dies, the plot will be fought over by land sharks.

In one of the saddest stories I have read, Rochelle makes ‘Noise’ her topic that includes silence as an indistinguishable part of it. It’s again a skillfully written story about the city of Bombay being within and without it. Jonathan D’Souza who went to work as usual in the morning vanishes in the wrong direction and guided by some unheard call lands up in Mathura without money or wallet. By that time he had forgotten most of his previous life. His mother Kay waits for him to return for days and months. His brother Wilson is soft in the head and never grew in mind beyond a few years. Time slowly covers them up and it’s already twenty years past Jonathan’s disappearance. Jon now is a beggar somewhere on the foothills of the Everest peak. Kay worries about what will happen to Wilson if she dies. She gives him away to her parish. She doesn’t know of his death even months after his death. She had stopped thinking of Jon. “Her oasis had come to be the ticking and chiming of clocks on different walls of the house. She never corrected them to synchronize. ….Somewhere far around, bigger clocks told her when the city awoke, when it slept, when it took a break and when it rushed. The city was a sea – the ebb and peak of noise were its waves. And, it was always there for her, awake in its factory sirens, vehicular blares and shrieks of tyres.” “She couldn’t hear much, but a new sound began to make its presence felt. A train chugging every half an hour.”

Thus, the ruthless city chugs on its long historical journey from Bombay to Mumbai to an uncertain future over the lives of people who either came under its tracks or were slippery enough to escape. Rochelle Potkar becomes the true chronicler of that city.

About the reviewer: Ravi Shanker N has published four collections of poetry, Architecture of Flesh (Poetrywala), The Bullet Train and other loaded poems (Hawakal), Kintsugi by Hadni (RLFPA) and a chapbook In the Mirror, our graves with Ritamvara Bhattacharya. Some of his poems have been translated to Italian, German and French. Some poems have been included in significant anthologies like the Red River Anthology of Dissent poems (Witness), Red River Book of Erotic Poems (The Shape of a poem) and Collegiality and other ballads – the Hawakal Anthology of Feminist poetry by non-women. Translated C K Januvinte jeevithakatha as Mother Forest (Women Unlimited) and Tamil Dalit writer Bama’s short stories as The Ichi Tree Monkey and other stories (Speaking Tiger). Co-translated Sri Lankan Tamil poems in a collection Waking is another Dream (Navayana) (with Meena Kandasamy) and a collection of Malayalam Dalit stories Don’t want caste (Navayana) (with Abhirami Sreeram.) Also edited and translated a collection of 101 Malayalam poems How to translate an earthworm (Dhauli Books, Bhuvaneswar.) He has also published a play Blind men write in Dec 2021 (Rubric Publishing).