Reviewed by Sally Naylor

Reviewed by Sally Naylor

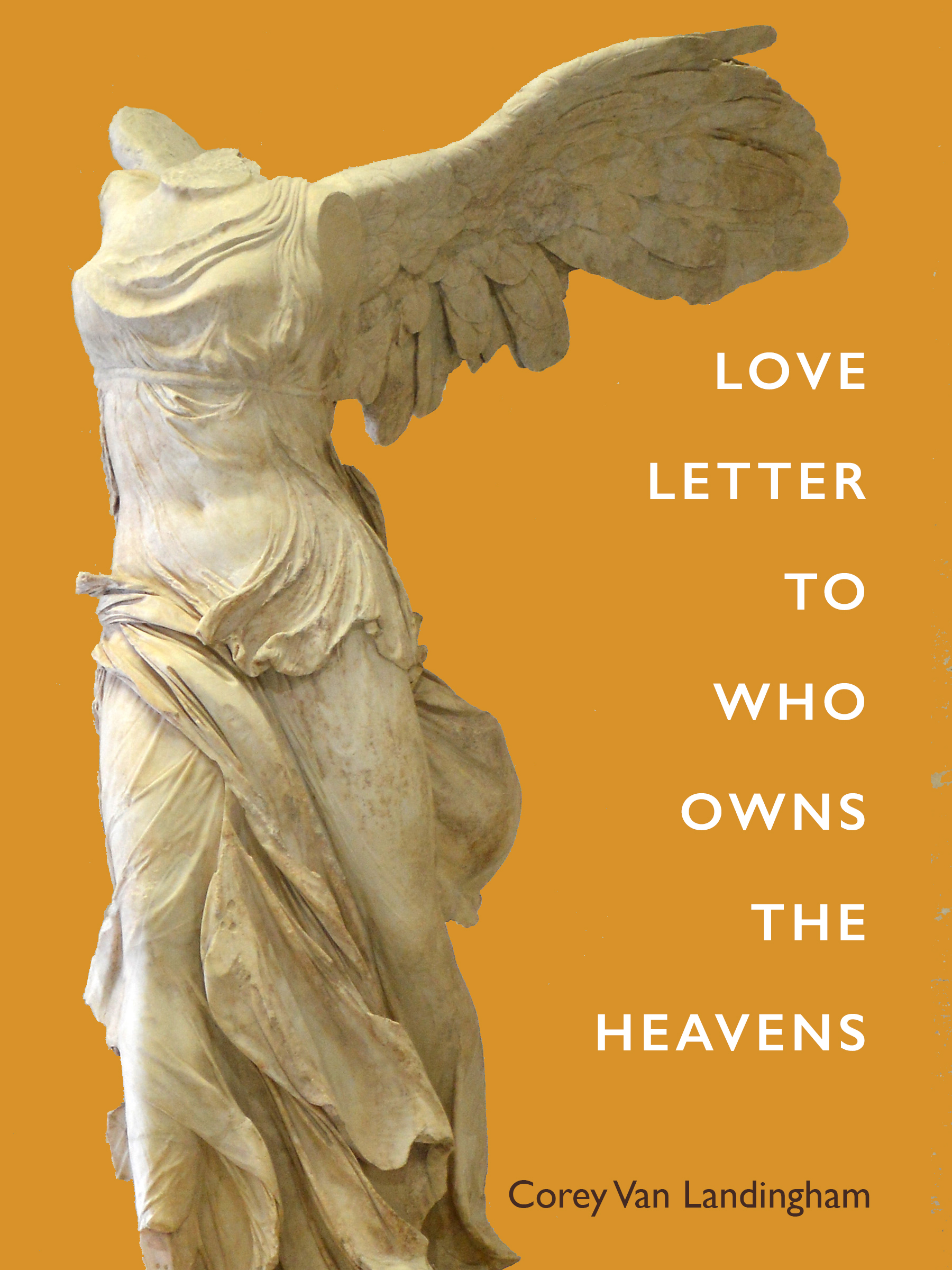

Love Letter To Who Owns The Heavens

by Corey Van Landingham

Tupelo Press

Paperback, Jan 2022, ISBN: 978-1-946482-61-7

Strange, disturbing, exciting. Love Letter To Who Owns The Heavens provides the initial scatter shot as we are spewed with and peppered by sensory startles. Whew! Whether it’s her facility with irony, history and memoir or in her many personal to universal shifts or the leaps in content or whether it’s the visuals or could it be Van Landingham’s facility with creating a disjoint juxtaposition of paired allusions? It is all these elements, as well as her coherence in the midst of unremitting oddness. The phrase tour de force springs to mind.

Van Landingham, fortunately, is in no danger of taking herself too seriously. The first page greets us with the dismembered hand of a statue thrusting its lone, attached finger to the heavens. The poems that serve as prologue and epilogue are separated from the first section of the book not by numerals or titles but with that image, which does its job and detaches us from any mood set by the lyrics. This image appears five times.

“Desiderata”, her prologue, is aptly named and explores warnings about the mechanization of humanity. She longs to project herself and a lover onto a screen, able to feel nostalgia, her scent then becomes textable. Yet she resorts finally to a prayer: Love gives us an ending to look forward to but concludes with a reference to the fall of Rome. She marries contemporary content like drone warfare and excessive force with a lovely classical diction, invoking words like spondee, employing the apostrophe in phrases like “O, beautiful boys of America”. We are treated to a celebration of anaphora in “Apolgia from the Valley of Inheritance”.

“American Diptych” reviews American history while “the Eye of God” rewrites it (are you ready?) with fifteen allusions: many are juxtaposed in an oddly satisfying manner: Ohio quarterbacks juxtaposed with Hannibal, the Pacific Fleet with the English painter Gainsborough and Verdi with the burning of Atlanta – all as a cavalry stampedes a chariot. Meanwhile military communications ask us; how copy? as our narrator then deftly whisks us off to Wrigley Field & Giotto as she concludes with Was blind but now I see. Effective? Yes, but some may require a deep breath. But then a delight like “Kiss Cam” pops up, and it’s hard not to want to be the woman bursting onto the screen alone while the stadium around her burns.

Van Landingham employs technique, even gimmick, well, but her lyricism is superb as in “When we saw our language carved in stone we fell in love with it a little and hoped ourselves, too, permanent things”. On a different note, and not to be missed, is her epistolary prose poem, a satirical romp titled “Love Letter to the President”.

Another startling and amusing moment occurs when Van Landingham attributes three descriptions of Hermes to Aeschylus, Homer and anon in consecutive lines. The focus of the poem, however, is on the drone, Hermes, not the god. But why not strut and play?

This book, not unremittingly cynical, also provides:

There’s hope in the study of things

That a lost world might stay a little longer.

That amid all the myths of departure

I could unhinge my jaw, become the hagfish, co-opt the monster

And just be there, slime-slicked, tracing my belly

against the bottom of the earth.

Of the ocean floor I know nothing.

That’s nice. Yes. That’s nice.

The book’s center is dubbed “Pennsylvania Triptych”, a narrative exploration into the Civil War via a mammoth painting on a scroll depicting “Pickett’s Charge”. In this lively prose poem experiment her point of view moves from spectator to battlefield into the image of the artist who paints himself into his canvas leaning against a tree. This series of prose poems varies both the format, shape and size of its prose sections. In one case the poem is printed horizontally. This historical section is sandwiched between two poems exploring her own “sext” life & adolescent urges on an imagined field trip to Little Round Top, Georgia.

The last third of the book zig-zags from restless youth, teen nostalgia content to kinky sex to World war II France and again back to drones. In “Love Letter to MQ-IC Gray Eagle”, she addresses the drone directly: “Show me my worth drone in a back alley” and asks if we are destined to be less human in the dark? Her subject matter appears to be an almost schizophrenic stream of consciousness, Despite erratic leaps somehow each individual poem draws the reader into its universe and we choose to go for that ride. Compelling. But we are left often without any contextual justification or linearity. Is it because poetry says there is eternity in the moment?

Van Landingham’s title poem, the last poem in the book, states that a word freed from the lips is in the air a kind of trespass – much like a drone. She cloaks the book in exposition, inquiry, outrage and even irrelevancy, while she questions the owner of the universe, stating “I’ll remember the words I once had to give you, on the porch, in private.” Aptly concluded: both infuriating and gratifying in its mystery. It catapults us beyond reason. This is not a book to be understood and traditionally deciphered. It is mostly free fall.