Reviewed by Vinita Agrawal

Reviewed by Vinita Agrawal

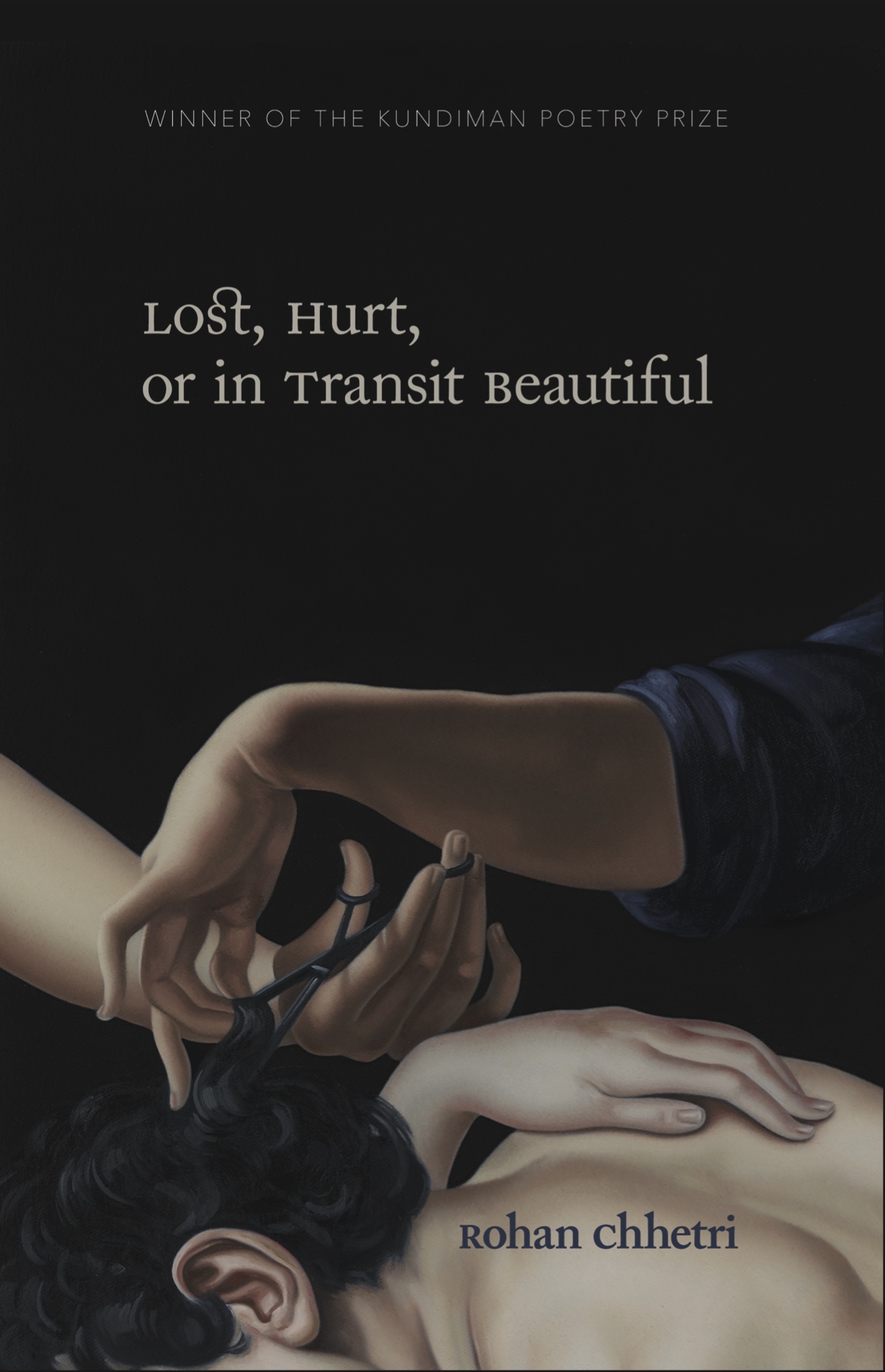

Lost, Hurt or in Transit Beautiful

By Rohan Chhetri

Tupelo Press

ISBN: 978-1-946482-54-9, 73pp, Oct 21, $18.95rrp

Antiphonal Mourning and Armageddon

here lie the bones of the deceased

who tried to hurry the unhurrying east

Rohan Chhetri’s second collection of poems arrives five years after his debut publication, Slow Startle. Lost, Hurt or in Transit Beautiful is intense, exquisitely crafted and honest to the point of redemption. The poems are classified into four sections—Katabasis, Locus Amoenus, Erato and Grief Deer. In the first section, Katabasis—there seems to come through to the reader, an exorcism of the past. An unravelling of a haunting grief, like a stiff fist unclenching and airing the fountainhead of wounds. There are many references to the speaker’s familial history in the verses here—particularly how they lived and died. As if whatever they endured, brought to the speaker’s own life unprecedented perspectives. Almost a glissade of experiences from one generation to the next, as though ancestry was a major source of learning and writing: “My history of nausea in the cold half- / Light of childhood, where did it come from?” (The Singing Bone).

Chhetri admits, “The legacies of trauma and fortitude, kindness and imperfections as human beings we leave behind” animates his work to a great extent with the larger question of place and “who walked these lands before me”. The first two sections in particular are laced with the awareness of the long geopolitical history of the Indo-Bhutanese border town that Chhetri grew up in. There is a sense of history-haunted-ness that the book begins with, a Katabatic plunge down “to the underworld for knowledge, for guidance. The underworld in this case being the colonial history of the land, the history of the ancestors and finally the speaker’s own personal and familial history.” The poems are rife with themes of revolution, soil, bloodlines, clans, mountains, fear, death, soldiers—all set against the landscape of the foothills of the eastern Himalayas.

Interestingly, “Lamentation For A Failed Revolution”, the third poem in the book, begins on every new page, with Bangla numerals or, let’s say, with vernacular markings. Almost like a font of revolution. There is always that “implicit tension” between language and violence in the book as a whole but in this particular poem, which recounts, in Chhetri’s own words “the last iteration of the Gorkhaland Movement in 2017, a hundred-year-old movement demanding self-determination and a separate Indian state for the Nepali-speaking population in West Bengal”, the poem’s performative qualities “reflect and depict this period of siege not only through the voice of a poet’s lamentation which itself falters and fails to remain objective” but through “the antiphonal voices of the women of the town”. He further clarifies, “the antiphonal section illustrates some of the ways the women have mobilised as a force of resistance in the long history of the struggle and draws from the lament tradition in ancient Greek. The poem itself tries to register that ‘stutter’ in the English language, that disequilibrium in the face of unspeakable violence, the sheer unspeakability when language fails and narrative must slant, resort to the fabular.” The poem is cross pollinated with lines, in the sense that a line could end and begin with a new one from anywhere in the left & right indented texts. For example, I read “Every failed revolution is a child. / Every revolution is a child grown before fire” as “Every failed revolution is a child / learning the edge of himself”. Chhetri deliberately allows the reader the liberty to interpret his lines in open-ended ways. When I asked him if he had considered the opposite strategy i.e. to lead the reader to what he had to say, a more ascertaining form of self expression, he replied, “I like that it can be read in multiple ways across the caesuras, the fractures in the lines are meant to play out the disruptions, the state clamping down, the gaps in information etc. The performative aspect of it allows opening up multiple sites of meaning as opposed to any single poet’s authoritative voice, or any one way of reading (the line), when the ‘more ascertaining form of self expression’ in fact has not much to offer in the face of actual, unspeakable violence and loss of lives. Hence the re-imagining of the antiphonal agency, the antiphonal women’s voices are subversive in the way that it seems to be speaking to a different reality than that of the poet’s eloquent mourning. In the ancient Greek lament tradition, the male poet was at the helm of leading the mourning and the women antiphonally answered by reading out a roll call of the dead and an account of their lives. Here, I try to reverse the roles a bit where they are recounting the story of the devastation and the violence wrought upon their lives quite suddenly one day as the troops swarm into town, subsequently foregrounding the antiphonal mourning as a powerful space of subversion…”

Chhetri’s collection conveys a compulsive sense of distance from his immediate surroundings. He lives in the United States, yet writes with nanoscopic clarity about his roots in the Himalayan belt. He writes intensely and poignantly about the India-Bhutan border town of the Eastern Himalayan region and that part of geography that cradled his early years and youth:

“I was a boy trying to get home, the city flinging me out.” (The Indian Railway Canticle)

*

“… in a language that excludes / themselves, & hence, is now rote, manifesto.” (Sebastian)

Perhaps poetry is a medium to expunge grief. A cathartic blueprint when written from a space of physical distance rather than from a position of embroilment. To this Chhetri pointed out that “this book, unlike my first, written completely in the US during the last five years, came out of that distancing and sense of exile which allows a kind of clarity. I suppose a sense of physical distance gives perspective to accept where you come from with all its beauty and terror, but we are not all allowed to escape the position of embroilment. Some write through it, within it, at the risk of persecution, and it is here where language is pressured and bludgeoned into utterance that poetry takes its truest form, which is something I have thought about more and more as I neared the end of the book, to not be too comfortable in this “exile” and to have a healthy suspicion for this “clarity.”

The imagery in Rohan Chhetri‘s poems is profound and remarkable and almost apocalyptic in scope. To quote a few lines from “Poem With Ritual, Broken Guardrail, Imaginary Novel, & Curse”:

“…Fall rain like a hose sluicing down the butcher’s platform.”

And “wounds like windows left unlatched in the blizzard.”

And this from “Lamentation For A Failed Revolution”:

“ ...They dragged

our children’s fathers down to the river.

Held them by the hair, pulled their tongues

out of their mouths taut like catgut.

Some looked embarrassed. So young some of them.

One cracked a joke. They all laughed.

Be still, someone whispered. The river raved

and raved eating up the moaning

turning hollow in our mouths.”

Commenting on his craft of building images and metaphors in his poems, Chhetri replied, “I suppose they are simultaneously mysterious and not at all. They come from varied sources and art forms like film, music etc., from years of reading, of studying and having seen that being done on the page by other poets until this “craft” becomes breath and surprise, which is your own learned skill fused through your particular temperament that has your imprint and can be no one else’s. That does not mean you don’t write out of a palimpsest of direct and indirect influences, I foreground this in the book with echoes of poets from Homer to Arvind Krishna Mehrotra to Pound and Auden that discerning readers can and will recognise.”

Also, there’s a deliberate sense of pace and pause in his work. He employs a studied sense of timing on tropes of violence, uprootedness and tales of the returning dead, tropes that by definition might provoke a poet to rip through its delivery and narrative. The extract below is one example of the studied, unhurried unspooling of one thought before moving on to another so that no nuance of what has been seen and chronicled is missed.

…At night, you hear the coyotes howl

& pray for the fawn, the only startled passenger

of the unit. No more than a few weeks old, flicking

its clean ears, as it wobbles by the bottlebrush,

not used to the stench of the animal hunger

that stops its mother still in her tracks. (Restoration Elegy)

When asked about the successful deployment of pause, pacing and timing in the context of the poems in the book, Chhetri remarked, “Unspooling is a great word to describe it, this technique is a holdover from my first book, of deliberately slowing down the narrative, that was much suited to the style and theme of my first book, an extended book of elegies. In this book, of course, I’m equally interested in disturbance, of how you can score varying music and pacing through syntax and enjambment and guide the tenor and pace of someone’s reading of the poems.”

Finally, the poems in this collection have an intriguing retractable quality—while they talk of failed revolutions, they speak also of homecoming in the same breath. They enunciate displaced communities in one gust, but also forge liaisons with a terrible loneliness of a solitary nature. Sometimes multiple existential issues of identity, caste, farmer suicide, class divides, homeland etc are swept into a single verse and the speaker engages with feelings of loss and hurt at a personal level. Chhetri’s disclosure on this phenomenon of inward and outward churning of content in his verses was this—“The movement of the book moves from the collective to the individual. I wanted to arrange it in a way where the reader needs to move through the thicket of the collective, to sometimes be comfortable in that opacity, to reach the lyric. So yes, definitely, there is the collective voice that gets rarified towards the lyric by the end (even formally through the sonnet) and the tension is played out throughout the book. Between the beauty of the region and the neo-colonial ravages of the land and its peoples. Between the nanoscopic lyric and the large narrative canvas of the baroque and its various folds… and so on.”

No matter where you live, Lost, Hurt or In Transit Beautiful will stir your senses and grip your imagination. It will invoke in your mind’s eye, unseen images of the land simmering at the foothills of the eastern Himalayas. It will strike a chord of compassion for what human beings endure and for what they pass on to posterity. Chhetri’s poems are an act of courage, a baring of the soul, written from the depth of his experiences, some as enigmatic as the title of the book itself.

About the reviewer: Author of four books of poetry – Two Full Moons, Silk of Hunger, The Longest Pleasure and Words Not Spoken, Vinita is an award winning poet, editor and convenor of literary events. She lives in Delhi, India.