Reviewed by Ketaki Datta

Reviewed by Ketaki Datta

The Grace of Distance

by Matthew Thorburn

Louisiana State University Press

ISBN: 978-0-8071-7076-2, 2019, 71pg

“Between the desire and the spasm

Falls the shadow”…

The Hollow Men, T.S. Eliot

The Grace of Distance is Matthew Thorburn’s seventh collection of poems, following on from the Lascaux prize winning book-length poem Dear Almost. The title of the collection intrigues me, reminding me of the well-known adage, “ Distance lends enchantment to the view”. Perhaps William Hazlitt, the seventeenth century English essayist, penned it.

Matthew Thorburn has divided the book in four sections, without any sharp thematic divisions or even any superscriptions for those sections. I think he deliberately has left it to the discretion of the readers, who may explain the poems in whichever way they like. The first and the third sections contain eight poems each, while the second and the fourth sections comprise seven poems each. In this era of reader-response criticism, the readers have the freedom to interpret the poems, judging them with the yardstick of their own comprehension. “ The Call”, which opens the collection, provides a call to the reader to become absorbed in the charm hidden in the subsequent pages. The boy who had slipped down the well in remote Anhui to surface in Mongolia, kept whispering to the ‘star-clotted’ sky , while swimming underneath. And the poet called down ‘into that dark glitter, awaiting a response from the abysm, being repugnant, irritated, later coaxing and cajoling till a voice ‘called back’. It appears, as though, the voice of the poet reaches the larger audience, at last. The meaning of meanings may be there, but ultimately, the response of the readers is what the poet waits for.

The Grace of Distance has an immediate appeal with a parabola of terse phrases and expressions turning into maxims. The poems of the first section have a wider spectrum of portraying the human emotions, drawing upon the spiritual wanderings through the labyrinths of one’s mind or hint of rebirth or reincarnation of human souls, as propounded by Lord Buddha. Irrespective of land or culture, proclivities of individuals or their moorings, the poet enjoys his journey of quest for the Truth or Ultimate Reality, as demonstrated in the following quote from “Your New World”:

You’ll come back as something else,

the monk says, but you won’t

know it, and you think, Okay,

what good is that?……Where’d

your new world go? The monk says

or you do. [cf. Your New World]

The poet rues the chopped-off ‘old oak tree’, whose reincarnation he has no idea about. However, the old stump serves as a ‘good place to sit’. As Paul Brunton, the philosopher, said that ‘Here and Now’ [in The Power of Now] must be our present concern, the poet too thinks of the mutilated stump, which has some utility to the people. Next birth is a chimera, reincarnation is an abstruse fact or an ‘imagined’ entity after all.

In “ There and Not There” too, the poet’s interest in spirituality comes into the open. “Journey from Spirituality to Reality” is interrupted by the ‘pale, matchstick fingers’ of his ‘five-month old son’ brushing his cheeks, jolting him back to reality while he writes:

I was trying to get outside my body,

figure out how to leave this

padded bag behind. I don’t mean

dying. I guess I was thinking about

the spirit, my spirit…”

While Thorburn speaks of spirit and likens it to a ‘white bird’ as seen in old paintings, he reminds us of W.B. Yeats who likens his spirit to a reincarnated bird ‘set upon a golden bough to sing’ (“Sailing to Byzantium”). In “A Speck in the Air”, Thorburn expresses his belief in the power of prayer that can usher in light through the otherwise impregnable facade of darkness:

My prayer goes further still

to where the dark turns to

half dark, quarter dark, and now

mostly light..

Echoing Coleridge:

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth all.

Re-echoing The Bible: “Let there be Light and there was Light.”

In the following excerpts, it is clear how Thorburn’s phrases turn into adages or even maxims:

“Words plus temples, that’s how you get to poetry in Chinese.”

“ And love is happiness said twice.”

“ Call it the grace of distance,

a starry sky above the pyramids

buried in sand.”

[ cf. Like Hours of Rain on Piles of Brown Leaves]

Out of the seven poems in the second section, the three poems that deserve special mention are, “Like a Light Left on For You” [on a Chinese dating site], “How Every Song Ends” and “ Forgotten Until You Find It”. Despite the inane demands of a Chinese dating-site, Thorburn beautifully dwells upon the word, ‘Love’ in “Like a Light Left on For You”. The varied definitions and similes are impressive:

Love, staple us together. Love, gum up

the works.Love

like no money down. Love like the rent

doesn’t come due.… Love like a light

left on for you. It’s not all about money

but some of it is. Love, unbutton our hearts.…. Love like hot peppers

sputtering in the wok, like four hands

in sudsy dishwater..”

[cf. Like a Light Left on For You]

In the poem, “ Forgotten Until You Find It” , the verisimilitude of the waxen image of Dutch Monalisa is explored. The poet’s urge for finding an image throb with life is fascinating:

“Dutch MonaLisa,” someone sighed

Or at least whispered

And someone else said, ‘Uh huh, yeah”.

The more I looked the less I believed

She was only an array of pigments dabbed

And daubed and touched..

[Cf. Forgotten Until You Find It]

In the third section, among the eight poems mostly begotten of the poet’s association with China and its people, just two to me seemed appealing. These are: “A Poem for My Birthday” [based on a poem by Ch’ang Kuo Fan, translated by Kenneth Rexroth as “ On his Thirty Third Birthday”] and “Loneliness in Jersey City” [bearing heavy influences from Wallace Stevens, the American poet]. In the former poem, the meaninglessness of a busy life compared to worthiness of a placid life at home, watching ‘old parents grow older’ has a serious connotation in this go-getter’s world, where each and every soul is scampering his way to success, a dizzy height of a lonely, yet enviable existence:

…Each day

follows a tunnel to its other end.Each day

a blue memo, something to mail, to shred.

[Cf. A Poem for My Birthday]

These lines invariably remind us of the famous speech of Shakespeare’s Macbeth:

Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow

Creeps in this petty pace, from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time…

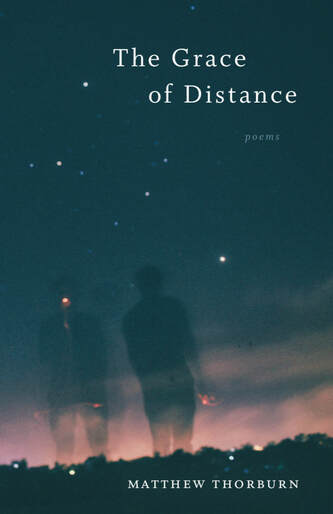

In the last section, influences of W.B. Yeats in “Driving Out To Innisfree”, memories of the long-lost leader of Oxford Movement, Cardinal Newman, the changing places of man and angel, trying hard to win the attention of the lady—are profoundly, faithfully and quite interestingly portrayed by Thorburn. In this precious collection of thirty poems , Thorburn tries to bridge the distance between past and present, between memory and desire, between unattainable and the things already in possession. Though you might not be able to judge a book by its cover, Michelle A. Neustrom’s cover design transports the reader to the star-spangled nocturnal sky to be amazed by its protean wonders. May this collection reach interested readers soon.

About the reviewer: Dr. Ketaki Datta teaches English literature at Bidhannagar College[Govt] , Calcutta, India. She is a novelist, poet, critic, translator, reviewer.