Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

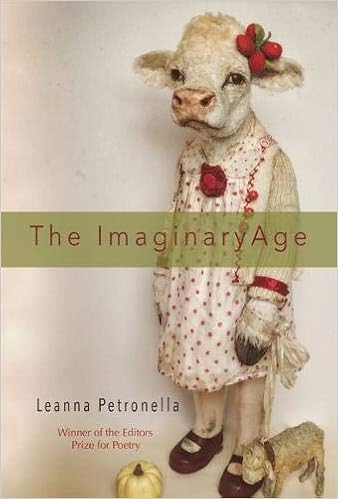

The Imaginary Age

by Leanna Petronella

Pleiades Press, 2019

$17.95, 76 pages

ISBN: 978-0807171523

Infandum, regina, / jubes renovare dolorem. “Queen, you order me to relive / unspeakable pain,” Leanna Petronella quotes Aeneas from Virgil’s Aeneid in “Infandum,” a poem about her mother’s death and her father’s response to it. The poems in The Imaginary Age take on hurt in its many forms, from grief to shame, but so often with stunning surrealistic imagery that transforms the emotion into – something else. Poems that deal with death, the frustrations of sex, the sense of loss inherent in growing older, often seem like dreams recovered on the psychiatrist’s couch. “Here I am, in memory’s safe, dark pocket.” (“To go to Marco.”)

Indeed, at first blush, so many of these poems have the ring of fairy tales and fables – “The Crocodile,” “The Hummingbird,” “The Butterfly,” “The Cockroach,” “The Fire Ants” – but dig a little deeper and you find the complex feeling underneath.

One of my mother’s friends

saw a hummingbird hovering by the funeral home.

She said, “Look, girls, there’s your mother.”My mother is not a hummingbird.

Her dead body is in a vase.

“The March Hare at Work” is steeped in the imagery of Alice in Wonderland. “Daily Bread” presents an interesting take on the family dynamics in the Hansel and Gretel story, as if considered by Sigmund Freud himself. “On Dating a Therapist” (!) makes reference to “Cinderella.” “Bedtime Stories” likewise starts almost like a fable. “Here’s the story: / After the gods made chairs, / they began with beds….” But then we read:

Beds became a place

for bad things.

The last animal moments before death

the death of someone that you love….

Later, in “Infandum,” Petronella writes:

So. My mother wanted blood.

Propped up in her hospice bed,she ate steak after steak.

We fed her every biteand I was afraid she would choke.

My father said, It doesn’t matter now,but it did. Who wants to die choking?

Who wants to die, period? She didn’t die chokingbut she did die in pain, in fear,

and this is somethingI can’t turn into something else.

The homely, everyday objects of our lives that we take for granted become iconic signposts, saturated with meaning, as time unspools. “My childhood was a safe, dark pocket. Now, nothing feels like my childhood djd.” Childhood was her close relationship to her twin sister, Georgina, captured in the long concluding poem, “To Go to Marco”: “Georgina is my twin sister. / Marco is her imaginary friend. / He is her imaginary friend. / I can see him.”

As they grow older, the twins have separate lives, of course. We all become individuals.

Egg with two yolks:

out of the shell,

we slide away from each other.

There’s something implicitly “abandoned” in the image of “sliding away.” Toward the end of the poem, though, she affirms: “I know we hold hands until the end, Georgina. I know we cling, our tiny wet hands soothing each other.” But it may sound more like a desperate wish than a confident declaration.

In particular, sex is a lonely adventure. In the final poem of the first section, “I Wonder What Happens Next,” she writes: “Sister, I fall in love without you. He is a Russian boy with whom I have nothing in common. But he is the first to breathe into my ear, so I imprint upon him, and it is duckling on duckling for a long time.” In the next section, it is precisely this lonesome love theme that dominates. “Even Now and Ever Since” begins “Rotmanov, your name was shame for years.” We assume “Rotmanov” is the Russian boy mentioned in “What Happens Next.”

Poems including “Like Love” (“You put your fingers in me like I was a vending machine.”), “To an Old Virgin,” “Throb for Throb” (“Down there is every vibrator / every boyfriend ever bought me. A graveyard, / sparkly pink, makes me laugh each time I find them.”), “On Dating a Therapist” and “Love Letter’ (“You shove into me, and this is the part of you I like. / I like your cock. I use you for it.”) explore the theme of love and sex and loneliness. “Skype Date” is a sad poem about internet sex. Though the title poem, “The Imaginary Age,” comes in the first section, the forlorn implications are perhaps best captured in the lines:

In some other life, I’d be a mother by now,

smug with the ability to love a husband.

But all of this is not to say that The Imaginary Age is steeped in melancholy. The language is so alive and the imagery too vivid for that. The simple poem “August” is more typical of Petronella’s style and outlook.

A thorn enters a pink jellybean like a tack.

It makes a cat toe, twenty. My toes make feetto walk sun-spanked concrete. Ice cream here,

vanilla scoops, amputated biceps of a butter god.Stranger, looking everywhere but the river’s

metal eyes, the fish don’t see you, either.

That image – scoops of ice cream like the muscles of a god – what a lovely imagination. All of the poems in The Imaginary Age bristle with this same inventiveness of language, a vision that seduces the reader with its charm, its warmth.

About the reviewer: Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore and Reviews Editor for The Adirondack Review. A chapbook of poems, Jack Tar’s Lady Parts, is available from Main Street Rag Publishing. Another poetry chapbook, Me and Sal Paradise, was recently published by FutureCycle Press. An e-chapbook has also recently been published online Time Is on My Side (yes it is). Another chapbook, Mortal Coil, is forthcoming from Clare Songbirds Publishing.