Reviewed by Ruth Latta

Reviewed by Ruth Latta

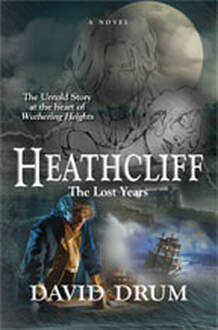

Heathcliff: The Lost Years

by David Drum

Burning Books Press

2019, $19.95,ISBN 978-0-9911857-1

Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, published in 1847, created a stir when it first came out and is still a much discussed novel, not only by English professors but also by everyday readers captivated by its ominous atmosphere and troubled characters, particularly the compelling relationship between Catherine Earnshaw, a prosperous yeoman’s daughter, and the foundling Heathcliff. Two questions continue to tease readers: ‘What was Heathcliff’s ethnic background?’ and ‘What did he do during his three years away from Wuthering Heights?’” The only clue in Brontë’s novel as to what he was doing while away, is Nelly Dean’s remark, when he returns well-dressed and successful-looking, that he has a “military” bearing.

David Drum addresses the question of Heathcliff’s whereabouts in his new novel, Heathcliff: The Lost Years. In this fast-paced, intriguing novel, Drum’s familiarity with “Wuthering Heights” and his knowledge of life in Britain and her Empire in the late 1700s are apparent. As Thomas Hobbes wrote, in “Leviathan”, life was “nasty, brutish and short”, especially for those at the bottom of the social ladder, and from reading Drum’s evocation of Brontë’s world, one understands why Heathcliff was so bitter and cruel on returning to Wuthering Heights.

Generally, Drum is faithful to Brontë’s novel, the one exception being Heathcliff’s age on being brought to the Earnshaws’ home. In Brontë’s novel, the housekeeper/narrator Nelly Dean describes what sounds like a preschooler: “a dirty, ragged, black-haired child, big enough to walk and talk, yet when it was set on its feet it only stared round and repeated some gibberish that nobody could understand.” Drum’s Heathcliff is older, an English-speaking runaway from a Liverpool school. The heart-rending scene of a little child creeping upstairs in the night and lying down like a pet outside the bedroom door of his one friend, old Mr. Earnshaw, is referred to but not dramatized in Drum’s story.

Drum is true to “Wuthering Heights” in his evocation of the bond between Cathy and Heathcliff, who become soulmates as well as childhood companions, and in his scenes depicting jealous Hindley Earnshaw’s abuse of Heathcliff, his father’s protege. After old Mr. Earnshaw dies, Hindley demotes Heathcliff from family member to farm labourer. His only friend is Cathy, who is becoming friendly with the children of a member of the landed gentry. Author Drum shows Heathcliff leaving Wuthering Heights in despair after hearing part of what Cathy confides to Nelly Dean on evening. Cathy says that she intends to marry Edgar Linton, and that her association with Heathcliff “degrades her. Because the novel is presented from Heathcliff’s point of view, Drum cannot include the rest of Cathy’s confidences as presented in Brontë:

My love for Linton is like the foliage in the woods: time will change it, I’m well aware, as winter changes the trees. My love for Heathcliff resembles the eternal rocks beneath: a source of little visible delight, but necessary. Nelly, I am Heathcliff!

After leaving Wuthering Heights, Heathcliff experiences the unjust world. His first encounter on the road is with a cottager, a farm labourer who owns no land but ekes out a living on the common land. The harshness of the enclosure movement is shown when the landlord seizes the common land by force – burning the villagers’ cottages. In Liverpool, Heathcliff sees people in abject poverty and decides that if he is to see Cathy again and pay Hindley back, he must “put iron in his heart” and find a way to become a rich, proper gentleman.

While working on the docks, he is promised by his businessman employer a substantial sum of money if he will go to sea. The wealthy man says that his ship, the Commerce, is engaged in the “triangle trade”, carrying, “English goods to Africa, black ivory to the New World” and returning “with sugar and rum to England.” Heathcliff doesn’t realize at first that the Commerce is a slave ship.

Drum addresses the question of Heathcliff’s ethnicity indirectly when he says that his employer’s servant, Pompey, is “the first negro Heathcliff had ever seen.” Presumably, then, Heathcliff is not of African ancestry. In both Brontë’s and Drum’s novels, people refer to him as a “gypsy”, in a derogatory way. Some scholars have suggested that he was Irish, since starving Irish people were pouring into Liverpool at that time, speaking Gaelic, not English. Other scholars say that Brontë intentionlly left his ethnicity ambiguous.

The Africa section of Drum’s novel is a realistic, horrific picture of the slave trade. Heathcliff hates “doing the devil’s work” but can’t do much about the “abysmal trade”. In Jamaica, where some of the slaves escape, Heathcliff is required to join the party to hunt them down, but is able to let only one escape to the mountains.

In Jamaica, the captain cheats the crew by paying them in Jamaica money, which is worthless in England. Back in Liverpool, when the owner of the Commerce fails to pay him as promised, Heathcliff takes matters into his own hands. In London, love leads him into a criminal gang and almost gets him sent to fight in America. In a remarkable stroke of good fortune, he becomes rich. All of his adventures occur in a grim reality in which duplicity and dishonesty are the order of the day and only the tough survive.

Drum’s novel ends before Heathcliff returns to Wuthering Heights. Heathcliff is hardened by his struggles to survive, but not embittered. The life-changing tragedy which makes him cruel to innocent people occurs after his return and is not presented in the novel. Heathcliff’s dreams about Cathy Earnshaw, which recur throughout the novel, hint at developments in her life that will devastate him.

When I studied Wuthering Heights in school, I was intrigued by the gothic atmosphere and the complicated characters obsessed with love and hate. At the time, the use of the two narrators, the similar characters’ names from one generation to another and the early 19th century language seemed to me obstacles to the story. David Drum’s Heathcliff: the Lost Years has plenty of atmosphere, conflict and obsession, presented in an historical context distinct and in an accessible way. It will appeal not only to those with some knowledge of Wuthering Heights but also who anyone who likes a dramatic action-packed story.

About the reviewer: Ruth Latta’s novel, Votes, Love and War, about the Canadian women’s suffrage movement and the first World War, will be published by Baico Publishing of Ottawa (info@baico.ca) in the fall of 2019.