Interview by Samuel Elliott

What were the origins of The Artist’s Portrait?

The idea for the book came at a point in my life when I just didn’t have time to write. I was working full-time in a demanding job and somewhere between the deadlines I started to see a vision, a bit like a daydream, of a woman, standing in front of a shack, waving a red cloth above her head as a biplane flew over the paddocks towards her.

Instinctively, I knew the woman was an artist, but I didn’t know anything about art or artists or biplanes for that matter and I was too busy to do anything about it, but the more I ignored this image the more I saw it . Then something happened that changed everything.

I was driving between Wollongong and Campbelltown for work one day and was hit by a B-Double truck. It sent me spinning across four lanes in front of oncoming traffic. The car came to a halt. It was bashed in on the driver’s side and facing the wrong way, but I was uninjured. I looked across the four lanes and thought, maybe it’s time to quit your job and write full-time, like you’ve always wanted to.

That’s where it started. I already had the image in my head, but that’s when I began to pursue it. I have to admit there were times when I questioned why I’d chosen to write about art – I was concerned that I wouldn’t do Muriel Kemp justice.

That’s where it started. I already had the image in my head, but that’s when I began to pursue it. I have to admit there were times when I questioned why I’d chosen to write about art – I was concerned that I wouldn’t do Muriel Kemp justice.

In the end, I couldn’t let go of it. I felt like the story had chosen me. The year after I started writing the novel, I enrolled in a PhD and as part of that I began to write a thesis on gender and prestige- comparing Australian women writers from the 1920s/30s (Muriel’s era) to the contemporary. The research for this highlighted the obstacles that confronted creative women (in any field), who chose to pursue their art.

The story is told through different timelines, at some sixty-or so years plus apart. Furthermore, you presented it through different characters perspectives. What challenges and difficulties did telling the story in such a way present?

Initially, I had no idea how I would tell this story. I started by researching the biplanes from the image, to give me a date. This led me to Australia in the 1920s which was a fascinating era. I read widely; history, biographies, a couple of manuals on how to fly a biplane. Themes began to emerge on how opportunities are shaped by gender. My next step was to explore what it was like to be a woman in Australia during the interwar years, then what it was like to be a woman who had ambitions to be an artist.

It required a lot of research; books, articles, old newspapers and documents, oral histories, documentaries. I also did hands on research; flying in a biplane, wandering around Sydney with bits of old maps, looking at artefacts, exploring the settings in the narrative.

The second timeline encapsulates the 1990’s and introduces the character Jane. Muriel is not a reliable narrator and I thought she needed a foil, someone who could keep tabs on what she was saying. I felt like I was auditioning characters for the part. I tried a few different people out before I decided on Jane. She seemed to fit.

I’m a similar age to, Jane. We both worked as registered nurses, had a child in the same year and were aspiring writers. Jane’s life though, is not the same as mine and despite my familiarity with the location and the era she lived in, I found myself doing a lot of fact checking.

Art is another important area in the story, and it was a major challenge. I knew, essentially that if I was going to write this book, I needed to understand the visceral response people have to art. I didn’t have a background in visual art and wasn’t exposed to a lot of art growing up. So, I immersed myself. I looked at art in books, online, exhibitions, painted. Listened to artists, talked to artists, read histories, reviews, biographies, opinions, watched documentaries.

I remember looking at a painting by Mark Rothko – bands of horizontal colour – and thinking, I’m not getting this. Then I turned to one of his earlier works; people standing on a subway. They were streamlined, some with curved necks. A strong feeling hit me. I remember thinking I could be in that picture – that could be me. That was the first time I felt anything like that. The next time was in response to a painting by Australian artist Vida Lahey, Monday Morning,(1912), which shows women at their work, an unusual topic for those times. But it was the same thing. It felt physical. It happened more often after that and it wasn’t dissimilar, I realised, to the feeling writing provokes in me or the passion people describe in response to their own creative bent, whatever that is. That’s when I started to understand the visual and tangible nature of Muriel’s drive.

One gets the impression that you’ve exhaustively researched Sydney of the era. How did you balance, all of what you found, which was necessary to the story, without drowning in all this fascinating, but potentially irrelevant subject matter?

I did get caught up in it a bit. And to write the narrative with the kind of familiarity I wanted, I needed to know what went on beyond the story.

You never feel like you’re going to know enough but in the end there’s only so much you can do. At some point, you have to just sit down and write it.

During one of the first conversations shared between Muriel and Jane, the latter requesting the former write her life story, Jane questions – ‘what if I stuff it up?’ – this seems like a question that pertains not only to Jane herself, but all writers in general. Was this almost a question you had posed to yourself? How did, or how do you overcome such pernicious self-doubt when it arises and by extension what advice would you give to fledgling authors who might be asking themselves that very question?

I did feel self-doubt, especially in the beginning. I’d quit my job to write this book. And while I had come to terms with the fact that it might never be published, I still wanted to write something I was happy with. I wrote about 80,000 words in the first nine months . When I went back and read it, I realised it was complete rubbish. I don’t mean, first draft – I can go back and fix it, sort of rubbish. I mean, it really wasn’t very good.

On reflection I was rusty. I hadn’t written for a while and I’d also developed a lot of preconceived ideas about what good writing was. These ideas jarred with my natural style and came across as stilted. That’s when I decided that if I was going to fail, I should at least fail in my own voice. I threw out 75,000 words. The 5,000 words that survived are the beginning of the book as it is now. Muriel was the only character that survived that draft.

Another similarity between me and the character Jane in The Artist’s Portrait is that we were equally trying to figure out who Muriel Kemp was and both thinking, am I going to stuff this up?

I have the same thoughts now as I work on my next book. On bad days I use the – go back to the story- strategy. Ie I sink myself into the story’s world and while I’m in there I’m not allowed to question whether I’m capable of writing it or not

To other aspiring writers I would say – persist. Write what you feel passionate about and where you feel the energy. Once you find that energy, pursue it. Expect that you’re going to have bad days, that’s normal, and keep going.

Beyond that I’d say ignore any advice that doesn’t work for you, including mine, and develop strategies that do.

You mention at one point, I’m paraphrasing the quote here a bit, but this notion of ‘legend rather than skill’ in securing a place in history, is one of the defining notions explored throughout the novel. Muriel’s legend seems formed and perpetuated by spurned men and the declarations of Claudine. Do you think that what Muriel was subjected to by many real-life female artists and is this the crux of what you wanted to explore?

Muriel is inspired by what life was like for women artists’ during the interwar years . We now generally acknowledge that the best of the early modernist painters were women in Australia- artists such as Margaret Preston and Grace Cossington Smith. But that’s in hindsight. The reality is women weren’t given that respect in their own era.

The conservative and very masculine art establishment of the time considered women artists inferior and second best and thought nothing of blocking their progress. Women artists were often pushed into the background and written out of history. The word ‘genius,’ was a term associated with males rather than females, just as men were considered the serious artists.

I came across some pretty scathing comments that were written about women artist’s in general. For Muriel, it’s not only gender she has to contend with but her working-class background – another strike. No matter how talented, I don’t believe she would have been supported by the art establishment or the well-known male artists of the time. My aim in writing her character was to re-imagine her life, as an ambitious and talented artist who’s given an opportunity. This opportunity comes in the form of another woman, Claudine, who not only sponsors Muriel but believes in her ability.

I didn’t come across any female artists in Australia who were supported in the same way Muriel was by Claudine. In reality, I believe Muriel would have been lost to history, not given a chance and disappeared. If Claudine had existed, she would not have had any female role models preceding her. As a strong, outspoken woman, she also would have attracted her own criticisms and barriers, as she does in the book. In The Artist’s Portrait Claudine is subjected to the conscious and unconscious biases of her era. Her relationship with Muriel was never going to be infallible.

One chapter opens with a quote from Adam Black, calling Muriel ‘a leech’, going on to say he moved on from her before she could suck him dry. I actually found that to be a fine description of the majority of males that revolve through Muriel’s life, is that a fair reading? Is Muriel emblematic of women of the time that were exploited by such types?

I don’t know that those men would have seen themselves as leeching on Muriel so much a Muriel usurping her position. The most common career path for women, at that time, was marriage and raising a family. As a woman you were expected to set aside any other ambitions in favour of the men around you. Many of the men during that time would have found it impossible to see Muriel as anything beyond an assistant to their own needs.

Muriel not only defies social expectations by painting but she’s extreme with it, unconventional by the most tolerant standards. She also has a fierce personality, a strong survival instinct, and she keeps going. She would have annoyed a lot of people.

Even in this generation, the more a woman speaks out, voices her opinions and advocates for her rights, the more criticism she attracts. In that same way, Muriel would have drawn more than the usual amount of backlash because she failed to succumb to the conventions.

To discussing your craft now, much of your published work before this novel has been short stories and short-form fiction, was there any difference between your creative process between those writing endeavours and your debut novel?

While there are obvious differences between a short story and a novel, my creative process is much the same for both. My ideas usually begin as a feeling or an image. I’ll research that as needed then let it stew in my head for a bit. In terms of being a pantser (winging it) vs a planner (writing and sticking to a plan), I’m definitely a pantser.

I do tend to stick to a plan in terms of my routine though. On writing days, I get up in the morning, walk the dog, have breakfast then sit down on the computer and work. I prefer to do creative work in the morning and research or admin in the afternoon.

The first draft is the most gruelling part of the process for me. I tend to rewrite as I go along, rewrite when I’ve finished the whole thing then I keep rewriting. I love rewriting but sometimes I overdo it.

I know The Artist’s Portrait has just come out, but are you currently working on anything?

I am! It’s very much at the beginning stages. Similar to The Artist’s Portrait, it started with a vision. I’m still finding my way in at the moment, trying to work out the characters and their voices. But it’s been good, as in it feels good to be working on something again.

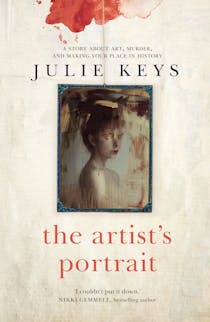

The Artist’s Portrait is available from Hachette here: https://www.hachette.com.au/julie-keys/the-artists-portrait

About the interviewer: Samuel Elliott is a Sydney-based author that has been published in Antic, The Southerly, Compulsive Reader, MoviePilot, Writer’s Bloc, Vertigo, Good Reading, FilmInk, Veranadah, The Big Issue and The Independent. He is currently working on his novel series, ‘Milan Milton: Heiress’ in between completing a degree and working two jobs within the television industry. Find him at:

www.facebook.com/samuelelliottauthor