Reviewed by Claire Hamner Matturro

Reviewed by Claire Hamner Matturro

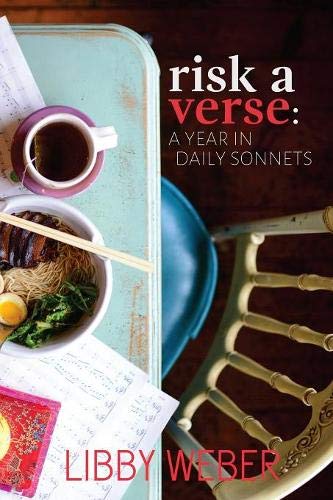

Risk a Verse: A Year in Daily Sonnets

By Libby Weber

Burrito Books

Paperback: 406 pages, April 20, 2018, ISBN-13: 978-0692960455

Libby Weber had a bold idea. She decided to write a sonnet, one sonnet, each day for an entire year. Her introduction to the book that resulted from this endeavor is a bit vague on the reasons why she did this. Rather than delve deeply into motive, the introduction emphasizes the assigned disciple involved—no skipping days, no writing ahead, no “sleep now, write later.”

Her disciple is an important aspect of this collection since a sonnet—somewhat of the anti-free-verse—is not an easy poem to write. There’s all that iambic pentameter, which can become sing-songy in a New York minute if the poet isn’t good at this. Then there’s the rhyme scheme with the three quatrains followed by a couplet. Thus, fourteen lines of poetry, rhymed and metered, for 365 days is quite an undertaking.

Delightfully so, this turns out to have been an undertaking Libby Weber pulls off with grace and aplomb. The result of her bold experiment in poetry is a lovely, thick book of sonnets that vary in mood, topic, and with some variation in format. Most of her sonnets are Shakespearean in form, but a few Italian sonnets in the style of Petrarch slip into the mix. Graduate students might never study this volume alongside of the Shakespeare that seems to have inspired the poet, but that doesn’t matter if one wants to enjoy a book of modern verse. There is much to praise and relish in this collection, even if it does not approach Shakespearean quality.

While there are serious, poignant poems in the collection, Weber’s cleverness and her sense of humor are often displaced to a good result. To paraphrase Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s “Constantly Risking Absurdity,” Weber does in deed bravely risk absurdity with many amusing, spunky entries such as “*ucking Sonnet,” the August 12th entry. Her sense of whimsy and even silliness are obvious in “Onomatopoeia Sonnet,” with its opening line “Drone. Ribbit. Humm. Snap! Whuff? Sniff. Shuffle. Howl!” She also writes sonnets about writing sonnets (“Sonnet 101”), which could have become too much of a good thing if Weber didn’t have a strong grip on it, which she does.

The poems which are the most fun (at least to this reviewer) are those about the poet’s dogs, some even written from the dog’s point of view. From example, in “A Sonnet by Giovanni, A Dog Who May Be Part Cat,” she writes:

Obtaining sustenance is such a chore

That there are days I lack the will to try.

For why should I have kibble on the floor

When lovely odors drift down from on high?

In yet another sonnet from her other dog’s point of view, Weber writes:

As I survey my kingdom, grass and trees,

My eyes are keen to catch the slightest twitch,

My nose is primed for odors on the breeze

Like me, the Feline Menace is a bitch.

And yet another about her dogs displays the poet’s wit, and her education, with a pun on Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem, “The Lotos-Eaters.” In “The Grossness-Eaters,” Weber writes:

“Courage!” she said, and pointed with her nose

And tail, with lifted paw, in perfect line,

“I sense there, underneath that bushy rose,

The origin of odors most divine.”

Several of Weber’s poems are autobiographical, a kind of diary in verse. For example, she writes with insight on lessons learned upon missing her bus in “On Public Transportation.”

Sometimes, when buying groceries in a store,

And, after waiting patiently in line,

One customer between me and the door,

A register will open next to mine.

…

To helplessly observe across the street

The bus, on which you are a frequent fare,

Depart, its tail-lights flashing your defeat.

Libby Weber avoids current politics, no doubt wisely so, but does have a passing comment on Vietnam. In her sonnet, “For Pop on His Sixty-Ninth Birthday,” she writes:

For some of them went off to fight a war

In which the country had a dubious stake,

To perish on antipodean shores,

For what was a political mistake.

Among the most poignant of Webber’s sonnets is one in memoriam for Philip Seymour Hoffman, 1967-2014, entitled “Goodnight Sweet Prince,” a reference from Hamlet, Act. 5. Letting the poem speak for itself is perhaps the best review:

An actor dies in New York every day

And leaves no more or less than any man;

Remembered for the roles he once portrayed

By colleagues, family, and ardent fans.

An actor died in New York yesterday,

Who with his presence stage and film had graced,

And while we mourn his loss, we yet betray

An underlying sentiment of waste.

The shadows swallowed yet another light

And for its lack, the firmament is dimmed.

He walked a long day’s journey into night,

The undertaking proved too much for him.

With addiction’s greater tragedy,

His passing marks the climax of Act III.

Risk a Verse is a mixed bag of poems, some funny, some serious, some good, other showing perhaps the strain of the daily obligation to write, but all are imminently readable, understandable, and enjoyable. Naturally, in an ordered daily ritual of writing a sonnet, some poems will shine more than others. Yet, the collection as a whole is vivid, insightful, fun, and engaging. Libby Weber is obviously an intelligent, well-educated woman with insights worth noting, and she shares her knowledge, wit, talents, and foibles with readers in an act of generosity. That Libby Weber would attempt the feat of sonnet a day alone is worth praise. Her success in meeting her goal and producing such an pleasing anthology should be strongly applauded.

About the reviewer: Claire Hamner Matturro is an honors graduate of The University of Alabama Law School, where she became the first female partner in a prestigious Sarasota, Florida law firm. After a decade of lawyering, Claire taught at Florida State University College of Law and spent one long, cold winter as a visiting legal writing professor at the University of Oregon. Her books are: Skinny-Dipping (2004) (a BookSense pick, Romantic Times’ Best First Mystery, and nominated for a Barry Award); Wildcat Wine (2005) (nominated for a Georgia Writer of the Year Award); Bone Valley (2006) and Sweetheart Deal (2007) (winner of Romantic Times’ Toby Bromberg Award for Most Humorous Mystery), all published by William Morrow, and Trouble in Tallahassee (2018 KaliOka Press). Coming in Spring of 2019: Privilege (Moonshine Cove), a steamy legal thriller noir set on the Gulf coast of Florida. She recently finished polishing Wayward Girls–a manuscript she co-wrote with Dr. Penny Koepsel–and awaits the happy news when her agent, the great, fun, funny, and radically energetic Liza Fleissig, places it with the right publisher. Follow her at http://www.clairematturro.com and https://www.facebook.com/authorclairematturro