Reviewed by Judith Swann

Reviewed by Judith Swann

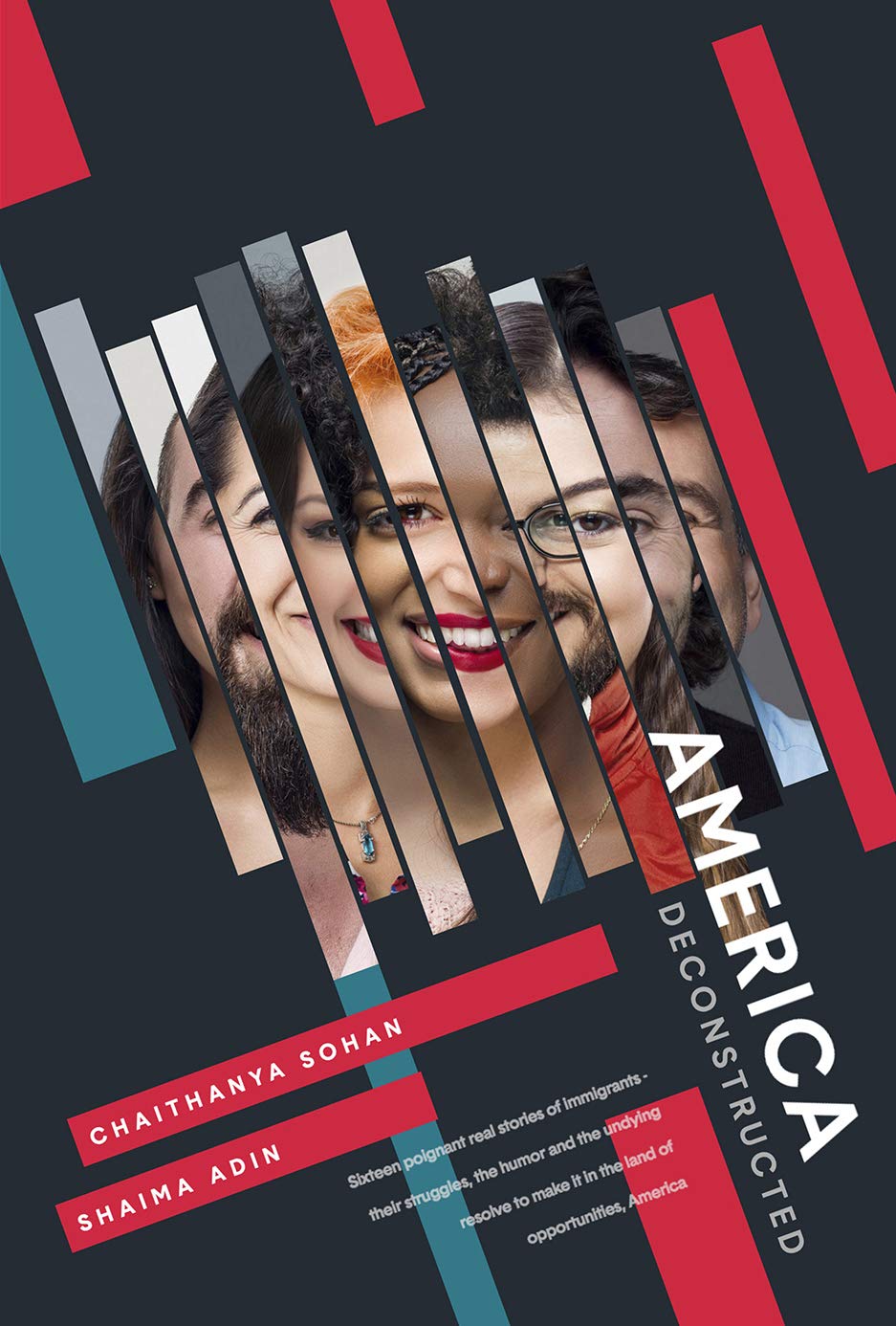

Deconstructing America

by Chaithanya Sohan and Shaima Adin

Motivational Press LLC

Paperback, 184pp, ISBN-13: 978-1628655520

In Chaithanya Sohan and Shaima Adin’s Deconstructing America sixteen writers who immigrated to the U.S. between 1980 and the 2013 parse “American-ness” through the lens of their experiences. They come from Afghanistan, India, Pakistan, the Philippines, China, Nigeria, Ghana, Mexico, Kosovo, Sierra Leone, and the UK. Some emigrated to another country before emigrating to the U.S; some came straight here. Some were very young, some grown up. Some had won a Diversity Visa; some were H-1B holders. Some started out as students. All struggled with loneliness and disillusionment, and yet all seem to have found a path to happiness.

Antonio Paris, Chief Scientist at the Center for Planetary Science and Twitter phenomenon (@AntonioParis) recently posted a mostly black photo sent from the Messenger spacecraft’s orbit around the planet Mercury, its camera pointed at us, two shining spots in the center left field, captioned, “Our planet and Moon as seen from deep space. No matter how much I zoom in … I can’t see any borders.” This planet is our home, and yet most of us give that name to only a small portion of it. Even when the idea of “home” seems to coincide with a political border, it is actually more nearly aligned with a common language and the collection of practices called culture. It’s hard to say which is the more dominant of these two, or if the second can exist without the first. Until you’ve been in a place where everyone, including the children, speak the local language better than you do, you cannot truly appreciate the emotional impact behind Azim Karimi’s characterization of his layover in Germany, “Everyone spoke German.” (p.28) A girl moving from rural Iowa to New Orleans, Louisiana can be as lonely and feel as alien as a young Afghan arriving in Kansas, but the New Orleanians won’t mispronounce the Iowan’s name and will understand her when she speaks. The Iowan wouldn’t have had to submit tricky bureaucratic paperwork or to accept a job well below her educational qualifications. Still loneliness is loneliness. We can connect on that.

Experiencing another culture is spiritually broadening, even if emotionally difficult. Chaithanya Sohan takes her African-American husband home to India only to have folks ask if he is related to Muhammad Ali, Will Smith, and President Obama (p.22). In California, they pronounced her name “Shit-tanya” until she switches over to Chai. (p.17) Ifeyinwa, who comes from Nigeria where there are 250 languages, says that “America is extremely accepting to one’s uniqueness,” but she still has a cry in the bathroom after a fellow student misconstrues her need for him to talk more slowly with a lack of intelligence. (p.43)

The storytellers in Deconstructing America call out America’s issues with driving, TV, income inequality, racism, and food. In his introduction, food is the trope that comedian Paul Varghese uses to illustrate a mother’s love. “Did you eat?” she asks, meaning “Don’t forget about me,” “I miss you,” and “I love you” (p.10) Our immigrants confront America’s 7-11s, Starbucks, Pizza Huts, and McDonalds; and the processed food of America leaves a bad taste in the mouth. “I always felt that the tacos in Mexico tasted better than in the United States…I now know the ingredients in [those] tacos made them so amazing. The ingredients were fresh, natural, and not processed in comparison to the U.S.,” writes Francisco. (p.113) “Even vegetables I ate all my life tasted different in the United States than in Kosovo,” writes Lisian. (p.99) This is a collection of people who eat their traditional foods prepared in traditional ways, despite the challenge of reproducing the magic that is a truly good meal here, where the vegetables are engineered and the tomatoes are sprayed and picked before they ripen. And furthermore, even with the best ingredients, a peach cobbler has a hard time replacing a good gulab jamun, when that’s what you crave. (p.21)

In this collection, we get multiple assessments of gender and body image, clothing, the American preoccupation with the commute-consume cycle, the replacement of feet and bicycles with cars, and the concerns of child-rearing. But the one topic that all our storytellers weigh in on is the concept of home. What does “home” mean to them? About half the writers say that America is now their home; the other half claims the land of their birth. It is always the last segment of the teller’s tale, a summing up, and the logic each writer uses to make their decision is always compelling.

One thing I would have liked to see is a clearer attribution—perhaps at the level of the chapter title, or perhaps in a separate table—to the name of each story’s author. We don’t often discover the author’s name until partway through the story, which can be disorienting. That said, I would love to see this book adopted into high school social studies curricula across the country. It performs a valuable, educational service while simultaneously being a good read. The first person point of view, the individual colorings of the voices, and the emotional depth of the stories give this collection both authenticity and interest.

About the reviewer:Judy Swann is a poet and essayist who publishes fairly frequently, both in print and online. Her book of poetry, Fool (Kelsay Books) was released in December, 2018. Her book of essays on the cartoon superhero Stickman (John Young) will appear in March, 2019.