Reviewed by Nina Murray

Reviewed by Nina Murray

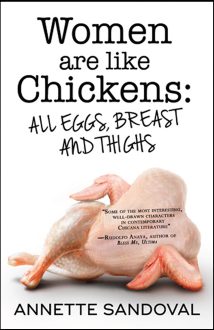

Women are Like Chickens:

All Eggs, Breast, and Thighs

by Annette Sandoval

Harvard Square Editions

ISBN: 978-1-941861-65-3, February 1, 2019, $22.95usd

First of all, let me say that none of the characters the reader cares about in Annette Sandoval’s novel really think that women are like chickens. The title is what the women know men around them think. The setting is San Francisco’s Mission district, in the early 1980s. The protagonists are a group of young women who must come of age in the predominantly Mexican community that expects them to be wives and mothers of the most conventional variety. The yarn Sandoval spins of their lives, instead, would make an HBO show-runner proud. Death, love, and food are never too far from each other; episodes of powerful yearning, comical justice, and occasional violence replace each other at a cinematic pace.

At the center of the novel are three friends. Alejandra Cernuda inherits the family restaurant very suddenly in chapter three, and must support the dedicated but somewhat cloistered crew that works there, in addition to keeping the business afloat. She is all of sixteen. Her sister Leah, fifteen, is yet to discover her secret talents (I won’t spoil it for you). Their friends Dulce and Tessa will defy expectations by attending Stanford and back-packing across Southeast Asia respectively. The sheer number of things women accomplish in the novel’s 327 pages—writing books, solving mysteries, rescuing babies, rescuing each other, falling in and out of love, and, finally, accepting posthumous donations of other people’s tattooed skins—is head-spinning. The plot lines are fresh, inventive, and cohere into a satisfying resolution.

If there is one thing that some readers may find befuddling, it is the power men exert upon the female cast of the book. Very early in the book we are given the chance to observe Alex and Leah’s mother, Mrs. Cernuda having this moment: “She paused to stare at herself in the full-length mirror. Her lifelong fear of living without the assurance of a man—first her father and then her husband—had come to pass. Why women crave total emancipation was beyond her.” That this attitude hold certain sway over the younger generation of the Cernudas is not surprising. What might stretch a reader’s credulity is the apparently complete suspension of the young women’s healthy double-sight when it comes to men. They go to mass and pray for a parking spot; they cover for a friend who elopes to film school by cultivating a myth of her being a martyr and a saint in the making—this does not appear to require any effort at all. Yet men appear to make them blind. Because male characters so consistently fall short of earning the kind of empathy Sandoval so easily secures for her female ones, the reader might find herself wanting to waive off a long-awaited kiss, even when it’s “slow and lingering, and then <…> firmer as his body pressed against hers.” It may be good, but we suspect it’s not going to last. Or matter, in the end.

About the reviewer: Nina Murray is a Ukrainian-born American poet and translator. She translated, most recently, Oksana Zabuzhko’s The Museum of Abandoned Secrets. Her debut collection of poetry, Minimize Considered, is published by Finishing Line Press.