By Daniel Garrett

By Daniel Garrett

“If folks want to pop off and have opinions about what they think they would do, present a specific plan…” —Barack Hussein Obama, president (2009-2016)

What are the principles that are worth keeping, the foundation of civilization, deserving of attention of imagination and intelligence, of appreciation and cultivation, despite the assaults of personality, passion, and perversity?

What if all the things that are said about us, the best and the worst, are true, the most important assertions depending merely on perspective?

What are the solutions offered by artists, intellectuals, and scientists, as well as other independent folk, to current problems?

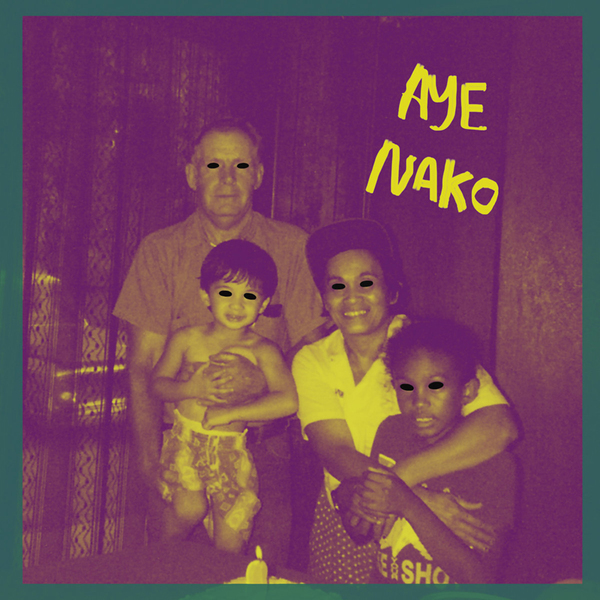

Romeo and Juliet in Harlem (2015), by filmmaker Aleta Chappelle, is a fresh interpretation of Shakespeare’s theatrical story of young love amidst communal hostilities, featuring strong performances in a contemporary and natural setting. The young suffer not only because of the hatreds of the old but also because of their own impulsive nature, ignorance and secrecy. Shakespeare’s play remains significant four hundred years after his birth, for his eloquent language, insight, wit, and tragic vision—time ratifies rather than reduces greatness. Who needs to hear an argument that the work of Shakespeare should be preserved? The work itself convinces. And yet making a case for conservatism is rarely done well—instead of discussing beauty and decency and dignity and intelligence and practicality and use as reasons to maintain institutions and rituals and works, arguments are put forth for how certain people do not belong or deserve the treasures of civilization. Those who are left on the margins, on the outside, begin anew—and sometimes that is creative and good, and sometimes that is crude, ignorant, and bad. Each case must be evaluated on its own. Each generation declares itself. The band Aye Nako, a group of young people making art, featuring bassist Joe McCann, vocalist/guitarist Mars Ganito (also known as Mars Dixon), guitarist Jade Payne, and drummer Angie Boylan, have produced the song collections Unleash Yourself (2013) and The Blackest Eye (2015), available on vinyl and via the internet, music collections that have tackled issues of self and self-division within a conflicted society and raised expectations and inspired comment: the first, a full album, Unleash Yourself, consisting of songs such as “Molasses” and “What’s Eating Me” and “Howl”; and the second, a short set, The Blackest Eye, included the songs “Leaving the Body,” “Killswitch,” “Human Shield,” “White Noise, “Worms,” and “Sick Fu*k.” The band has traveled around the United States, performing in a range of venues from basements to museums. Mars, a young person of color, grew up in the American south, but the band Aye Nako was born in Brooklyn—and the music has a complexity of influences.

Everyone inherits a world—a climate of influences, a geography and population and sound and temperature of influences. Some inherit—or come to claim—more than one world of influences. What is most important, tradition or the new? What is most urgent, the demands and pleasures of the present, or the promise of the future? The poet and essayist June Jordan, commemorating time, affection and desire, and the ephemerality of significance, wrote, “Infinity doesn’t interest me / not altogether / anymore / I crawl and kneel and grub about / I beg and listen for / what can go away / (as easily as love) / or perish / like the children” in a poem collected in the book Things that I do in the dark: Selected Poetry (Random House, 1977), called “On a New Year’s Eve Poem.” The narrator in the poem refuses the perfection of the distant object or scene, insisting on intimacy, on the perception and pressure of body against body—life, movement. June Jordan asserts a different sense of what is of value, and in danger: “but all alive and all the lives / persist perpetual / in jeopardy / persist / as scarce as every one of us / as difficult to find / or keep / as irreplaceable / as frail / as every one of us,” going on to insist “all things are dear / that disappear.” I wonder: Is sensuality as significant as compassion, as significant as knowledge, as significant as justice, as significant as compassion, dignity, diligence, discipline, liberty, and logic? Is anything more significant than a love that enlightens and nurtures?

Every generation asks and answers its own questions—and those become culture, history. Aye Nako’s The Blackest Eye considers how matters of self are shaped by world matters—especially regarding class, race, gender, and sexuality. “Leaving the Body” has a fast, thrashing introduction, churning, dense, spinning, with lyrics in which a narrator recognizes bad influence but also claims her own spoilage. One person’s attitude infects another person’s attitude. “Killswitch” has a rough sound, and seems, again, not afraid of self-recrimination—which can seem a rare honesty, or worrying. One wants both self-confidence and self-criticism, and, finally, self-correction. “Human Shield” has terrific guitar riffs—clear and fast. “Where the hell would I be without the awful things inside me?” the singer asks. In “White Noise,” the narrator declares, “You’ve got me bleaching my skin. / Are you linked up with reptilians?” and “How will you ever tell us apart?” The white noise is propaganda. The white noise is mental disturbance. The white noise is music. The white noise is attractive and repellent. The texture of “Worms” is dull and propulsive, naïve and raging: “racial sentiments are spinning way off-track” is one line. “Sick Fu*k” considers the presumptions of social interactions, with pain and irritation—and, as well, contains an assertion of desire.

In the July 8, 2015 New York Times, when considering the Aye Nako six-song extended play collection The Blackest Eye writer Ben Ratliff wrote, “On its Facebook page, Aye Nako, from Brooklyn, lists ‘non-college rock’ besides ‘queercore’ and ‘homopop’ as its genre descriptors. That’s good, because it challenges what might be your first assumption: This band gets close to the details of what was long ago called ‘college rock,’ trebly, fuzzy and slightly feckless,” then Ratliff went on to detail the ways in which the music and lyrics complicated that initial impression of predictability, especially in the thematic insistence on cultural conflict—racial strife and gender assumptions—made personal. Pitchfork agreed: the music site’s reviewer Jes Skolnik wrote, “The guitar lines, vocal interplay, lyrical poignancy and pointedness, and song structures on The Blackest Eye avoid predictability and heavy-handed formulae; there are plenty of stylistic curveballs” (August 12, 2015). The band Aye Nako was chosen by The Village Voice (October 14-20, 2015) as “best garage band” for the paper’s Best of New York 2015 issue, and the citation said “their latest collection thereof, The Blackest Eye, is a much-needed punch to the face of the status quo,” while also clarifying the origin of the band’s name: “a Filipino phrase expressing frustration that has no direct translation to English.”

Internet Interview: Questions for Aye Nako’s Mars Ganito by Daniel Garrett

“Be who you are and will be / learn to cherish / that boisterous Black Angel that drives you / up one day and down another,” begins the poet Audre Lorde’s lyric work of encouragement, “For Each of You,” from The Black Unicorn (W.W. Norton, 1978). In it Audre Lorde acknowledges the nearness of pain and power, and the necessity of both imagination and pragmatism in survival, advising, “When you are hungry / learn to eat / whatever sustains you / until morning / but do not be misled by details / simply because you live them.” How many people remember not to be misled by details? Such details are the motivation for most of us much of the time—containing a great deal of the history of the world. Lorde counsels us to be honest, and to remember: to see courage and fear, need and hope—she advises love and warns against convenient beliefs. Who can resist convenient beliefs, especially when they come shrouded in the colors of novelty and progress? Musicians, like all of us, are attracted to the old and the new—and cannot always tell the difference. Will Aye Nako be able to meet its challenges—of art, of life, of politics? The band members of Aye Nako have been bassist Joe McCann, vocalist/guitarist Mars Ganito, guitarist Jade Payne, and drummer Angie Boylan, though, Mars Ganito recently told this writer writer that Angie Boylan is no longer the drummer. I asked Mars to answer a few questions, sent February 17, 2016; and I received the answers March 10, 2016.

Garrett: How did the members of Aye Nako meet, and why and how did you all form a music group?

Ganito: We all met through mutual friends and through volunteering at Willie Mae’s Rock Camp for Girls in Brooklyn. I think boredom and the love of making music is the why and how of our start.

Garrett: Some of Unleash Yourself (2013) is very rhythmic and thrashing but also sounds surprisingly charming. I must admit I’m thinking particularly of “Molasses,” but it’s true of some of the other songs as well (and that may have something to do with the youth of the band and its singer). Were you aware of a certain appealing lightness in the sound, especially in the singing, despite the punk rhythm and speed?

I wrote “Molasses” on December 31st of 2009. I can’t quite remember what I was envisioning the song to sound like, but lyrically, I was just thinking about how I was getting older and supposed to be an adult and how I felt like a late bloomer. I didn’t mean to make it have a sort of lightness, I think my voice is just soft.

Garrett: What kind of work went into the recording The Blackest Eye (2015)?

Ganito: Jade recorded and mixed it. We recorded most of it in our practice space, some at an elementary school and some at my apartment.

Garrett: There have been a lot of great rock musicians, Elvis Presley, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, The Beach Boys, The Doors, David Bowie, Patti Smith, The Clash, Talking Heads, The Police, and, among others, U2, R.E.M, Kitchens of Distinction, Nirvana, London Suede, Death Cab for Cutie, Coldplay, and Vampire Weekend. There are a good number of imaginative and talented people of color who have originated, created, or delved into rock music, from Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Bo Diddley to Jimi Hendrix, Tina Turner, Prince to Bad Brains, Living Colour, and Fishbone to TV on the Radio and Murray Lightburn of The Dears and Kele Okereke of Bloc Party. Do you have any particular thoughts regarding any of these musicians?

Ganito: I’m into a handful of those bands/musicians you mentioned. It’s funny you mention Bloc Party. I was recently remembering how I saw Kele Okereke on the cover of Butt magazine back in 2010. I liked a few of their songs when Silent Alarm came out but I didn’t get that into them til I read that interview and realized that he was gay. I just want to see more queer black rock stars.

Garrett: Do you think that the song “White Noise,” on The Blackest Eye, which has been interpreted as being a response to racial divisions and expectations, and about racial fetishism, could be expanded to relate not only to a particular experience of being active in a small personal or social space but to the larger society as well?

Ganito: Oh hmm, I haven’t noticed it being interpreted as my experience with smaller social spaces. It’s definitely a comment about society at large. It’s about how whiteness is centered in everything. From the reason all my birthday, shooting star and wishing well wishes were to be white to why, in books, unless explicitly stated, it is automatically assumed that characters are white (i.e. the Twitter explosion about Rue from Hunger Games). It’s why most (white) people can’t easily name bands with black members. It’s why children of immigrants like me don’t speak their native tongue. Our parents wanted us to only use English, to fit in, to assimilate. In America, being multilingual is only impressive if you’re white. White supremacy is why people equate black power with white power and why people insist #AllLivesMatter because they know #BlackLivesMatter isn’t focused on or centering white people.

Garrett: Do you know of bands such as First World Problems, Girlpool, Glazer, Iceage, Pure Disgust, Sick Sad World, Sneaks, Tenement, Trash Kit, and The Young Lovers?

Ganito: I do know most of those bands because I’m friends or friends of friends with them 🙂

Garrett: Who are the musicians whom you now consider artistic peers?

Ganito: To be honest, I think a lot of my band friends are on another level above us, but I would say Downtown Boys, Speedy Ortiz, Potty Mouth, Joanna Gruesome, Didi, Vagabon.

Garrett: Are there philosophers, historians, and writers whose work you find sources of knowledge and insight?

Ganito: Black friends, black tumblr, black podcasts

Garrett: “In lust we trust,” a line from the song “Sick Fuck,” is the kind of line one might expect from a rebellious person—but it is also the kind of line that one might expect from any young indulgent person, even the most conformist. Certainly, many of the songs heard on the radio and via the internet are about sexual indulgence. How do you distinguish such an affirmation from the predictable?

Ganito: It’s queer sexual indulgence. They don’t play that on the radio 😉

Garrett: There has been much more attention given to critiques of assumptions about gender rooted in biology in recent years. Is there any thought you have about transgender issues that could be of help to someone trying to understand them?

Ganito: Tone down the assumptions, especially the entitlement you think you have to ask about people’s genitals. Keyword—People. Not specimens. Gender and sexuality are not inextricably linked. Stop embarrassing yourself because we all know our friend Google can be accessed 24/7. Read. Listen.

Garrett: What do you think about President Obama’s presidency, his statements, efforts, and accomplishments, and how he is received?

Ganito: I don’t think we’ll ever have another president who will talk about if folks wanna pop off.

Garrett: What do you hope for the future, in terms of culture, particularly music, but also in terms of political progress?

Ganito: Straight white boy bands and “Battle of the Bands” being a thing of the past, more black punks starting bands and getting recognized, the phrase “take off your shirt”” never being shouted again, Brooklyn Vegan comments section closed. I don’t know the exact science to make these happen, but I know some part of the formula involves the disintegration of white supremacy, toxic masculinity, and capitalism.

Thanks Mars—good health, much creativity, and joy to you and yours!

Purchasing Information, Blackest Eye: https://dongiovannirecords.bandcamp.com/album/the-blackest-eye

Sound Cloud, Unleash Yourself: https://soundcloud.com/ayenako

Daniel Garrett has written about art, books, business, film, and politics, and his work has appeared in The African, American Book Review, Art & Antiques, The Audubon Activist, Cinetext, Film International, Offscreen, Rain Taxi, The Review of Contemporary Fiction, and World Literature Today, as well as The Compulsive Reader.