Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

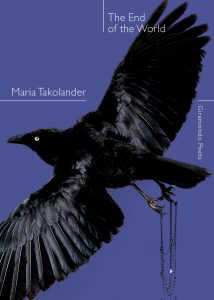

The End of the World

By Maria Takolander

Giramondo

ISBN: 978-1-922146-51-9, April-2014, PB 144pp, $24.00

As the title implies, Maria Takolander’s The End of the World makes no pretense at sweetness or ease. While there is tenderness in the poems of childbirth and domesticity that open the collection, the collection has an underlying ferocity which takes the reader below the superficial into the heart of meaning, as revealed by the intensity of each moment it encounters. From the start, we are thrust into the visceral heart of female experience, from the nausea of morning sickness, brought on by Darieusecq’s Pig Tales, to the hunger of Pica, the shock and delight at seeing an infant through ultrasound, and that simultaneously painful, shocked, and awestruck moment when you and your child settle, post-birth or “Post-partum”:

but next to my body you hulk and settle. There you lie,

strangely hungerless, intense as a nucleus.alive with an intelligence of I know not what.

Men wage war to make something this real,

There is a hallucinatory quality to the work – moving between nightmare and dream, between maternal bliss and terror, between utopia and dystopia. In some ways the work in the first section is utterly domestic. The reader becomes voyeur as we watch a family sleeping, crying out in dreams in “The Interpretation of Dreams”: “not these darkling hallucinations of a brain/already willing away the night on its pitiful past.” Through the domestic ordinariness of a television, a dressing table and a pot plant, we witness the destruction of a family to the Black Saturday fires. It’s simultaneous horrible and familiar at once; Lynchian the way it takes us through the detritus and details: “On a dressing table/there is a gold cylinder of lipstick,”. The loss is far more intense for the matter-of-fact way in which it is narrated, mingling the lurid details of death with the insistent remnants of life.

The second part of the book moves outward, into an historical perspective. The poems explore place and nostalgia, rootlessness, and war. As is the case with all the poetry in the book, the poems don’t ease us in gently. The reader is right there, complicit in destruction, suffering the pain of loss, and weathering the Nordic cold of myth and human frailty. One poem, “Missing in Action”, is a catalogue of loss, recording the demise of family members. Another, “Huskies”, takes the concrete image of the cold weather dogs off-season in order to illuminate the human condition, in a way that harkens to the final poems in the collection: “They hunt the future,/the ethereal vision in the distance, /but they will never be fast enough.” The section finishes at ‘the end of the world’, in both senses of the word, taking us to the wind blown streets of Punta Arenas, Chile, Cusco, Peru, and Bunos Aires, Argentina, where “Cats laze in the shade of an earth-quaked tomb, stacked with coffins spilling skulls and bones.”

The final section of the book is simultaneously the most intense, and also the funniest, combining a very dark vision of the human race with a sharp wit that provides a great deal of fun amidst the carnage. The poems explore a series of historical cases or works, turning the situations round and exposing the prejudices underlying them. One of the wryest examples is “Degeneration”, a pastiche on Max Nodau’s book Degeneration, written in 1892, which took as its premise the idea that art has a degenerating effect. Takolander opens the categories of degeneracy up to include the poet:

The problem with the poet is that she lacks the rigour

to adapt herself to the existing – the cause

of her dwindling – and becomes an idle meddler,

a cavalier visionary, monstrously ignorant of reality.

Other poems poke fun at Sigmund Freud (“golden Sigi”), and explore an underculture: misogyny, greed, lust, fear, prejudice, and hatred, concluding with the anthropomorphism of animals behaving like humans, unravelling the myths and stories we tell ourselves about our degree of civilisation. Overall the collection is unsettling, powerfully realised, and full of a sharp edged realism that is no less hard to take even couched in metaphor and heavy symbolism. These are intense poems that often hold an ugly mirror to who we truly are with all our pretensions. Nevertheless, there is something earthy and satisfying in the reflection, even as we see our foibles magnified. It is, after all, as Takolander so beautifully puts it, “life, pure and gluttonous, that committed/this glorious violence upon you and me.” (“Post-partum”)

About the reviewer: Magdalena Ball is the author of the novels Black Cow and Sleep Before Evening, the poetry books Repulsion Thrust and Quark Soup, a nonfiction book The Art of Assessment, and, in collaboration with Carolyn Howard-Johnson, Sublime Planet, Deeper Into the Pond, Blooming Red, Cherished Pulse, She Wore Emerald Then, and Imagining the Future. She also runs a radio show, The Compulsive Reader Talks. Find out more about Magdalena at www.magdalenaball.com