Reviewed by P.P.O. Kane

Reviewed by P.P.O. Kane

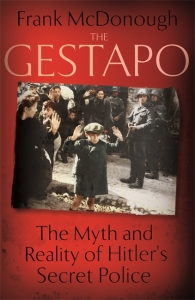

The Gestapo: The Myth and Reality of Hitler’s Secret Police

By Frank McDonough

Coronet

2015

ISBN 9781444778052

In popular imagination, in films and on TV, the Gestapo are generally portrayed as brutal and sadistic thugs. While this is not entirely false – ‘enhanced interrogations’, to use the euphemism, did occur in certain instances – it is misleading when we look at how the Gestapo operated in Germany (the Altreich) itself. There, the Gestapo had at most 16,000 active officers, most of whom were career detectives rather than young Nazi ideologues with law degrees; though there were a fair few of those too. In Nazi Germany hybrid organisations, the personnel a mix of party and state, were not unusual.

Those 16,000 officers had to police a population of about 60 million; and clearly could do so only by consent. The upshot being that the Gestapo was in the main a reactive organisation, dependent on denunciations from members of the public. And naturally many such denunciations were spurious, ill-founded or motivated by envy or malice. A waste of time.

McDonough begins his book by looking at how the Gestapo – or the Geheime Staatspolizei, to give the full title – came into being. A power struggle between Himmler, Goring and others, with Himmler ultimately emerging the victor. Later chapters examine how the Gestapo tackled various ‘enemies of the state’ (or ‘enemies of the German race’, that might be a more accurate way of viewing matters). The Christian clergy and communists were seen as the biggest threat to the new order at first; then social outsiders, marginal unproductive groups, were the focus: we are talking here about habitual criminals, homosexuals, the long-term unemployed, anyone who criticised the regime or refused to conform.

Amongst these outsiders, I was interested to learn of the Edelweiss Pirates: a gang of working class youths who’d scrawl anti-Nazi graffiti and have the odd ruckus with the Hitler Youth. Hooligans and yobs, in a society where the upstanding citizens were complicit with evil. They even dressed in a distinctive garb, these lads; it was a whole other subculture.

In 1935 the Nuremberg Laws introduced a slue of new crimes for the Gestapo to investigate: it was forbidden, for example, for Jews and Aryans to have sexual relations. And as we know, further anti-Semitic measures would be taken in time.

Thoughout these chapters, McDonough discusses a number of cases in detail, making for the most part excellent use of the Gestapo case files held at the HstAD archive at Duisberg. These cases provide a necessary quotidian grit.

At the close, McDonough looks at how members of the Gestapo fared at Nuremberg and in later post-war trials. In 1945, in the trade-off between social stability and justice, the Allies tended toward stability (Stalin was now the threat) and most Gestapo officers were exonerated. Even when convictions did occur they were woefully inadequate. Werner Best, a Gestapo big cheese, makes for an interesting illustrative case. He was sentenced to death in Denmark, but appealed and in the end served only three years, being released in 1951. A later investigation of Best in West Germany in the late ‘60s floundered as well; the case was adjourned due to ill health in 1972 and quietly dropped. Despite ill health, Best lived on for another 17 years. He died in 1989 in his eighties, a free man. With justice like this it is little wonder that in May 1960, when the opportunity came, the Israelis decided to kidnap Eichmann and try him in Jerusalem.

This book is a valuable contribution to our understanding of the nature of the Gestapo in Germany.

About the reviewer: P.P.O. Kane lives and works in Manchester, England. He welcomes responses to his reviews and you can reach him at ludic@europe.com He blogs at: