Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

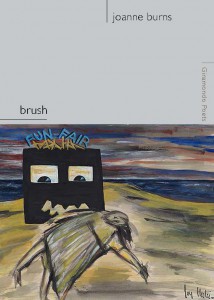

brush

By Joanne Burns

Giramondo

ISBN: 9781922146717, $24, Oct 2014, 112 pages

Many times I’ve picked up brush, read one poem and then had to put it down for a bit. To call Joanne Burns’ latest book of poetry challenging would be an understatement, but there’s so much going on in each of the poems, that I found myself coming back to them again and again. This is work that won’t scan easily; in either sense of the word. At times, the poems are so full of parataxis, clever juxtaposition, ironic aside and syntactical juggling, that the poems, taken too quickly or in too large a dose can create a kind of vertigo. However, I couldn’t leave the book alone. It kept drawing me back, one poem at a time, and each time I returned I found something new; something powerful:

your book of dreams: it always fails

the exam, why not think of yourself

as an ambulance, then there will be

no need to dial triple O…(“verb”)

The first section, “Bluff,” is a pastiche on the world of business, biting hard against the self-important business man, against governmental brewhaha, and against conspicuous consumption:

does your share portfolio ache

unlock yoru teeth in the adrenal winds,

the facilitationality of a sea of nomadic desks

doesn’t need to be seen to be believed – (“factoidal”)

Anyone aware of the corruption of language that becomes natural when with working in a large corporation will smile knowingly at Burns’ sharp wit. These poems are as funny as they are harsh, excoriating the businessman’s pretentions with “a projected avalanche of/cornflakes and ketchup/debt…” (“chain”)

The second section, “In the Mood”, is a little warmer. The poems take us into the realm of the domestic and the personal. We begin with the kinds of dreams we’ve all had where we’re not sure which door will open or which sign will yield: “Ithaca/was rather disappointed at the absence of meaning/but glad she could remember how to swim.” (“foyeristic”). There are ordinary irritants, such as the eye floater in “Wink”: “my own little arachne. Not a regular visitor, but a modenst/soothsayer and spy.”, food (cheese rolls), washing machines, disposability, a ball of string. The poems still pull together disparate imagery, but in a way that is recognisable.

The ‘title section’, “brush: a series of day poems” contains a number of poems of place, setting, scenario. These are almost bucolic, straightforward, and easily taken in, though no less powerful for that:

the intonations of the charcoal

ocean from sand to horizon, we sip

on coffee’s prophecies as the morning

rises…(“sip”)

Though Burns is never overly sweet, this work is more vulnerable, and begins to show a bit of the personal – with less distancing wryness: “I’m an untidy town oh save me – “ (“frame”), offering up dreams to the reader like gifts: “inside the destination there were to be surprises” and self-help advice like the best humour: “so where’s that 9 grain goethebread” (“choir”).

As the name suggests, “road” is a bit of a travelogue, taking the reader along on a journey that hovers between the sublime and the ridiculous. The scenes here are mapped out, through familiar spaces – country towns, cafes, bars, beauty parlours, exhibitions, new views/vistas, bus and car rides all filled with the sounds of the road, sibilance, puns, word play, aphorisms, slogans, redaction, and meta-poetics: “I have though about poetry as hypertension/as I write these recipes for first aid and scholarship” (“cheap”)

In “delivery”, the poems delve deeply into memory, moving so far back into childhood that memory takes on a slightly surreal quality, from the birth in “delivery” through the origins of poetry in youth, Bondi beach and young love, travel and the sting of experience:

a boat eating a rock’s history

too much sun in your diary

things scar your pockets like

awkward souvenirs; the hand

me down vis fades into another

century the secret of the retsina

rotting old photograhs still here (“from ‘crevice’ a mneumonica”)

The book finishes with the wry humour of “Wooing the owl (or the great sleep forward)” which takes us out of time and place and opens out into a kind of grand unknown, where specific cultural images like the Morris Minor, popcorn doonas, the Knack’s “My Sharona” (o my charona), Jehovah’s Witnesses, the Veronica Lake look, and even a touch of Yiddish (“chutzpah”) are disembodied, and transformed through a removal of context. The images are ‘ambiguated’, though in the title poem for the section “the great sleep forward” Burns talks about disambiguation: “disambiguate here now” – a subtle reference perhaps to the yogi mindfulness slogan of the 1960s Ram Dass’ “Be here now”. In this section, it’s as if we’ve passed through time, moving through life with all its sequences, and are now in a kind of timeless afterlife where anything goes and everything is connected: “at last the stitches in time’s/pesky little roster break it’s/a chronologically free for/all you’re everywhere at once” (“trill”). The final section is a perfect ending to a rich and complex work that repays multiple readings, revealing new meaning, new allusion, and new wordplay each time.