Reviewed by Anne Graue

Reviewed by Anne Graue

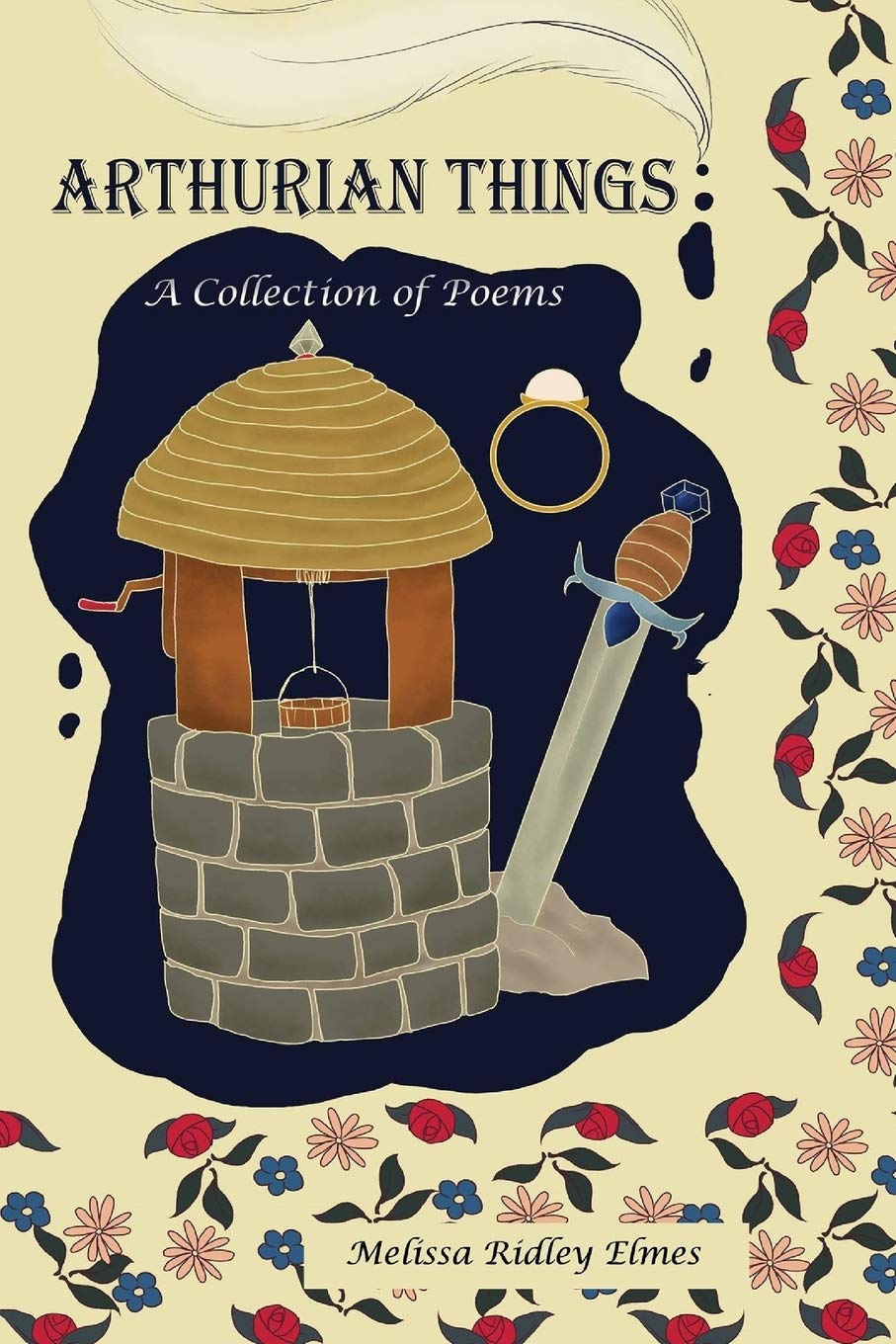

Arthurian Things: A Collection of Poems

by Melissa Ridley Elmes

Dark Myth Publications

Jan 2020, Paperback, 120 pages, ISBN-13: 978-1652488514

The Arthurian legend never disappoints. Containing all of the necessary elements of an old English tale of royalty and intrigue, it delivers on its promised themes of chivalry, honor, and nobility, adding in quests and adventures for good measure. In Arthurian Things: A Collection of Poems, Melissa Ridley Elmes makes imaginative use of the legend while presenting that world from a myriad of points of view including those from artefacts, animals, or the familiar characters of Arthuriana in a fly-on-the-wall perspective retelling the stories of legend and inventing some new ones. Elmes makes effective use of the many voices she’s created in her collection of formal and free verse narratives and monologues, supplemented by illustrations by Anna Elmes that complement the poems.

In a preface to Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur, the publisher William Caxton offers reasons for publishing the work, and among them is “the intent that noble men may see and learn the noble acts of chivalry, the gentle and virtuous deeds that some knights used in those days, by which they came to honour [sic].” The 21 books in Malory’s work detail the birth, life, and death of King Arthur, his Round Table Knights and the women in their lives. Further into the work reveals the aforesaid not-so-gentle and virtuous deeds that from a 21st Century perspective, or a feminist perspective read as misogynistic and self-serving. A few of the poems in Elmes’ collection employ the feminist lens, although this doesn’t hold true throughout the entire book. Elmes’ intent seems to be to highlight the traditional stories of legend from unexpected points of view of objects, animals, and people that inhabited Arthur’s Camelot.

Throughout the collection there are some delightful moments of whimsy and comedy. The 3-poem sequence from the points of view of Arthurian flies, ants, and bees all requesting unionization comprise one of those times when a bit of satire meets King Arthur’s Court. In “Arthurian Flies Request Unionization” the flies chant their presence “on the battlefields,” and “in the sculleries…and bedchambers,” insisting that “there is no place in the world where we are not.” They chant in unison to be named in the history of the realm which seems to be their only demand. Arthurian ants and bees also demand representation and recognition for their contributions to noble society. Such satirical riffs interspersed throughout the collection add some levity to the more woeful tales emanating from Arthurian literature. Limericks and a poem in which the famous sword Excalibur deals with imposter syndrome in a TED talk add to the playful nature in which anything can be given a voice and a perspective.

A sequence of fourteen sonnets, “Thoughts in Passing: A Sonnet Cycle,” appears near the end of the collection and each sonnet is titled after a person important to the Arthurian legend. Major Knights of the Round Table—Galahad, Gawain, Kay, and Lancelot—are given their platforms as are Arthur, Guinevere, Morgan Le Fay, and Merlin. In these sonnets, Elmes lends a voice to each title character in poems which mostly adhere to the Elizabethan sonnet form, including the requisite number of lines ending with a rhyming couplet. The form is a container but also a space for Elmes’ language to adopt the rhythm and vocabulary of Arthur’s England. In Sonnet XII, Lancelot says, “I didn’t even want to come to court, / but sense of duty beat out common sense,” in measured iambic pentameter. In Sonnet X, Galahad introduces himself as “the Grail Knight, pearl of matchless price,” and goes on to reveal his thoughts on the other round table knights who are flawed, break laws, and bend rules, which makes him question the worthiness of knighthood altogether. Two of the sonnets in the sequence give voice to Isolde and Guinevere, women who betrayed their husband-kings for knights they fell in love with. In a moment of feminist ferocity, Isolde remarks, “How fragile masculinity can be” and Guinevere reveals that her only love is meant for Lancelot, not Arthur. These glimpses of a feminist response to Arthurian patriarchy masked in chivalry are refreshing in this ambitious collection.

Taking on a legend is never an easy task, and the Arthurian legend is ages old and feels as if it were set in stone. In her collection of poems giving voice to Arthurian Things, Melissa Ridley Elmes has undertaken to add to the canon of Arthuriana poems that imagine voices, tell tales, and create scenes in which the once-and-future King Arthur and his knights are endowed with humor and humanity.

About the reviewer: Anne Graue is the author of Full and Plum-Colored Velvet, (Woodley Press, 2020) and Fig Tree in Winter (Dancing Girl Press, 2017) and has poetry in SWWIM Every Day, Verse Daily, Rivet Journal, Mom Egg Review, Flint Hills Review, Feral: A Journal of Poetry and Art, and in print anthologies, including The Book of Donuts (Terrapin Books, 2017) and Coffee Poems (World Enough Writers, 2019). Her book reviews appear in FF2 Media, Adroit, Green Mountains Review, Glass Poetry Journal, and The Kenyon Review. She is a poetry editor for The Westchester Review.