Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

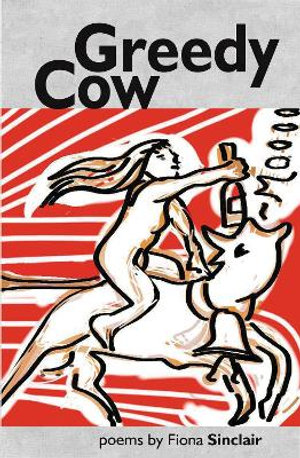

Greedy Cow

by Fiona Sinclair

Smokestack Books

Aug 2021, £7.99, 46 pages, ISBN: 9781838198879

“Greedy cow” is a term whose origin lies in Chaucer’s Clerk’s Tale in his Canterbury Tales, about the patient Griselda –

O noble wyves, ful of heigh prudence,

Lat noon humylitee youre tonge naille,

Ne lat no clerk have cause or diligence

To write of yow a storie of swich mervaille

As of Grisildis pacient and kynde,

Lest Chichevache yow swelwe in hire entraille!

Chichevache was the “greedy cow” with a woman’s face that fed only on good women –

like the patient and kind Griselda, a peasant girl who promises to honor her husband the marquis of Saluzzo’s wishes in all things. He puts her through a series of cruel tests. She aces them and in the end the marquis confesses what he has done. They live happily ever after. Not to say Greedy Cow is a fable about patience rewarded; in her self-deprecating way, Sinclair also writes about her desires and her weight, so those resonate as well. But still it’s a lens through which to consider this lovely book.

Greedy Cow is a series of poems about finding love in middle-age, and it does conclude happily-ever-after-like (patience rewarded). The last lines of the final poem, “Still,” with the two side by side in Istanbul gazing at the Bosphorus:

We embrace like a couple on an anniversary card.

And given the choice, I would edit down the rest

of my life to live in the still of this moment.

The collection opens with Sinclair’s humorous experiences with internet dating, from the pervy responses to her profile picture to flirting with emoticons; “over the week I virtual two time / men from Rochester and Deal.” Soon enough, though, she begins a relationship with a man – “our steps synchronize like Fred and Ginger” – and over time they adjust to one another. So much of the narrative is the poet’s discovery of and reaction to her man’s past, so different from her own, and the adjustments both have to make. After years of taking one’s own routines for granted, that’s not easy. “Not as young as they feel” contains the observation:

But, in middle age,

sleep must be prepared for, like a journey,

a check list of pills for pain, cholesterol, blood pressure…

“A month’s trial…”: the relationship’s still tentative, up in the air. It’s hard to get used to being a couple, “after years of solitary living”:

you long to replace your siren shift

with comfy leggings and Tee shirt,

stretching out in your bed like a cat before a fire.

Read a chapter or two on the loo,

encouraging your coy bowels to poo

without anxious ‘Are you all right?’ up the stairs.

There’s also jealousy, a theme that recurs (as in the poem, “Warning”). “Driven by the Iago voice in your head,” the poem, “Curiosity” begins, she looks for signs of infidelity, breaks up with him for a minute. “You send his belongings packing to the shed, / but his email, ‘everyone has a past’ / gets his foot back in the door of your life.” She’s continually learning about that past. “Trying to map you” begins:

I was a debt collector once: usual static shock

at some new revelation about your past,

a politician’s deflection to my When was this?

Alluding to the Who song, “My Generation,” she muses about his “hope I die before I get old attitude,” and the poem concludes:

Trouble is, when our relationship first began to close in on my

own back-ground, my gambled Let’s not talk about the past,

was accepted by you with poker player cool.

Over time, as my secrets burst their locks,

I expected us both to show our hands,

but you grip onto our contract like a winning betting slip.

A short poem, “Locked out” begins, “Sometimes you are a sealed strong box with no spare key,” but over time they begin to adjust to one another, as “A changed man” suggests, and another short poem, “Out of Step,” reads:

Occasionally now my Canterbury amble

does not keep time with your south London strut,

so I must adjust my steps to yours…

Eventually they decide to marry. “She values her independence, / friends writing me a ‘Tatler’ life,” she ruefully observes in “Day Return,” and the poem goes on:

Too proud to confess I wanted a man beside me.

Then you pitch up; belated for kids playing in the garden.

In “Sparkler” they go shopping for rings, in Florence. In “Speechless…” they marry, her aunt behaving oddly. The poem ends sweetly:

Later, in photos, she sees the something borrowed

that day was her mother’s beauty,

wonders if the old Hollywood hair, make up, smile

reminded her aunt of the dead sister,

still unforgiven for her good looks…

Toward the end, newly married, both in their sixties, her husband acquires a motorcycle! In “Rush” she writes that though he has tutted at “middle aged men on bikes ‘They can’t handle’, mutterings of / ‘Trying to recapture their youth’ are forgotten.” She confesses to a bit of jealousy, “as if I have reluctantly agreed to an infidelity.” But then she, too, falls in love with the bike, riding pillion, his biker chick sidekick. Indeed, it’s almost a threesome, as she writes in “Ménage”:

And just as I followed you on to planes to daredevil destinations,

friends purse their lips as you get me, at 60, on the back of this bike,

and from far off, what was meant to be your affair becomes a ménage,

as I watch the weekly weather report for the next fine days

and our holidays hijacked, we hop on the bike and race out of lock down.

All of her friends are aghast, as she writes in “A chorus of disapproval,” but in the year of the pandemic she’s been reminded all too often that catastrophe always lurks right around the corner, and now, in her 60’s, she writes in “Windfall,” “over the last few years, / I have felt untouchable as a king’s favorite.”

No humility nails down Sinclair’s tongue in these poems, as the clerk had warned against in Canterbury Tales! Sinclair is funny and touching and vivid and honest in all things.

About the reviewer: Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore and Reviews Editor for The Adirondack Review. His latest book, Catastroika, was published in May 2020. A chapbook of poems, Jack Tar’s Lady Parts, is available from Main Street Rag Publishing. Another poetry chapbook, Me and Sal Paradise, was recently published by FutureCycle Press. An e-chapbook has also recently been published online Time Is on My Side (yes it is). Another chapbook, Mortal Coil, is forthcoming from Clare Songbirds Publishing.