Interview by Tiffany Troy

Interview by Tiffany Troy

Javier Sinay is a writer and journalist based in Buenos Aires. His books include Camino al Este, Cuba Stone (co-authored), and Sangre joven, which won the Rodolfo Walsh Prize. In 2015, he was awarded the Gabriel García Márquez Prize for his article “Rápido. Furioso. Muerto” [Fast. Furious. Dead], published in Rolling Stone. The Murders of Moisés Ville is his first book in English.

Robert Croll is an artist and literary translator originally from Asheville, North Carolina. He first came to translation during his undergraduate studies at Amherst College, where he focused on the short fiction of Julio Cortázar. He has since worked on texts by several authors including Ricardo Piglia, Hebe Uhart, Gustavo Roldán, and Juan Carlos Onetti.

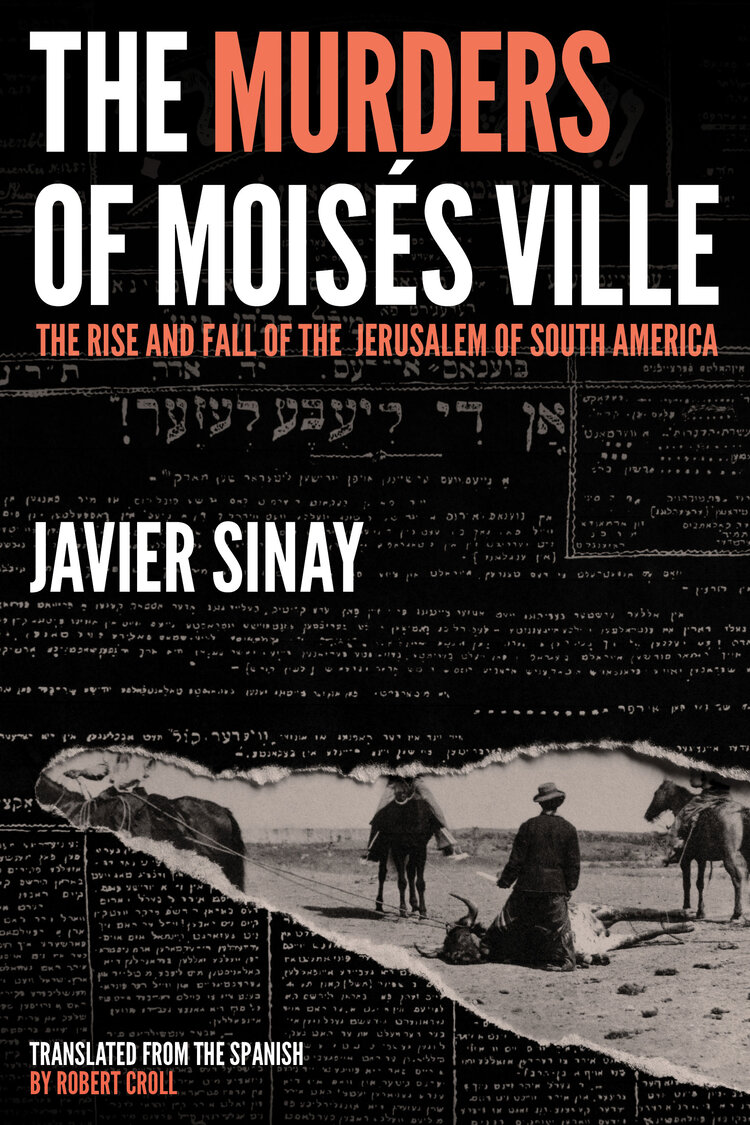

In The Murders of Moisés Ville, award-winning journalist Javier Sinay investigates a series of murders from the late nineteenth century, unearthing the complex history and legacy of Moisés Ville, the “Jerusalem of South America,” and his personal family connection to a little-known period of Jewish history in Argentina, linked to his great-grandfather Mijl Hacohen Sinay.

Tiffany Troy: Javier, what is the journey like, to uncover your family history and the truth of what happened in Moisés Ville?

Javier Sinay: It was very interesting because I didn’t know anything about my family past, the town of Moisés Ville, or my great-great-grandfather.

I knew nothing about Grodno, in Belarus, the place these people left when they came to Argentina. The best thing about the investigation was that I found myself to be a link in a chain—I came to understand much more about myself, including why I love journalism and literature, and why all my family, my mother, father, and grandfather all have libraries and lots of magazines at home. Understanding oneself better, it becomes possible to imagine what will come with future generations.

Tiffany Troy: You mentioned that to go back to your family history, you had to take a reading course in Yiddish. What was the process like for you?

Tiffany Troy: You mentioned that to go back to your family history, you had to take a reading course in Yiddish. What was the process like for you?

Javier Sinay: Very difficult. Hebrew and Yiddish are different languages, though the alphabet is the same. Just as English and Spanish are two languages that share the same alphabet. But I didn’t know the Yiddish/Hebrew alphabet.

So, first I needed to learn the letters, the aleph, the bet, and so on. Then it was Yiddish, which is something like German mixed with bits of Hebrew and Russian: really difficult. I spent a year studying Yiddish and took two courses, more for reading than speaking. I can’t really speak but I can read some Yiddish, and for four years I worked with the help of a translator. I could read the titles and know whether a text might be useful for me or not. If it was, I’d take it to the translator. It went like this: I’d write on the computer in Spanish, while she read from Yiddish and spoke in Spanish. The process was a little complicated, but it worked.

Tiffany Troy: My next question is for Robert: what is the act of literary translation to you?

Robert Croll: That’s a tricky question to answer. Sometimes I simply think of it as the slowest form of reading. It’s a creative process, but one with very specific ethical concerns and constraints.

For example, I need to keep in mind the fact that I’m translating into English, which has such dangerous cultural dominance. I don’t want to uncritically repeat the ideology of the world I grew up in and impose it on the text. I’m trying to learn through the act of translation and move past the narratives of history I’ve been taught, implicitly or explicitly. The works I’m drawn to all tend to involve some element that isn’t necessarily new but seems new to me.

Tiffany Troy: How did you get into Spanish and translation, specifically translation of Argentinian authors?

Robert Croll: I was lucky. Growing up, my school had me studying Spanish at a basic level from kindergarten onwards. My grandmother also spoke Spanish, not because of any heritage but because she was fascinated by the language; she died before I had much to say, but I think I inherited that affinity. I began to feel a deeper connection to the language after my teachers introduced me to Latin American literature. Translation felt like a natural way forward because one of the authors I studied, Julio Cortázar, had done some major translations into Spanish. I’ve always thought of translation as a way to understand language more generally—I learn just as much about English as Spanish because I have to constantly assess what is possible in English.

Tiffany Troy: What did the process of collaborating on this translation of The Murder of Moisés Ville look like?

Javier Sinay: In the beginning, I received two chapters translated by Robert. Then, a few months later, I received the whole book. Then the back-and-forth process started—a few words, you know, little things, which I marked as suggestions because I’m not a native speaker of English. For example, we were talking just a moment ago about the expression “in reality,” which is really common in Spanish, but I didn’t know it existed in English. So when I read it in the book, I asked if it’s better to put “actually” or “in reality.” But I don’t know, you decide Robert.

Robert Croll: It’s strange, we wrote back and forth throughout the process, but this is the first time we’ve really spoken face to face, so we owe it to you for bringing us together. A while ago we were hoping to do a joint residency, but all those plans were cancelled amid the pandemic.

Javier Sinay: We also worked together on And We Came Outside and Saw the Stars Again: Writers from Around the World on the COVID-19 Experience.

Robert Croll: Restless Books came up with the idea for that project right at the start of lockdown, while everyone was just barely processing what was going on, and Javier contributed an essay about his experience in Buenos Aires. Translating it brought me some valuable perspective beyond my own uncertainty at the time.

Javier Sinay: The chapter we worked on together is called “The Life of a Virus.” It’s really journalistic, with stories from people I’ve interviewed here in Buenos Aires. I don’t think there is another text quite as journalistic in the book; the collection is very literary. But I think it’s okay to give some context and facts. For example, I read that one coronavirus particle is 17 million times smaller than a human being.

Robert Croll: It’ll be interesting to see how the piece works over time because the data keeps evolving. It’s a document of where things stood in the moment when you wrote it.

Javier Sinay: Now in 2021 things are very different. I think the book came out in August 2020, so it was another world with no vaccines and Trump still in power.

Tiffany Troy: Did any facts shift for you as you investigated the murders? Or perhaps did your perspective on your family history shift over time?

Javier Sinay: You know, the most “shocking” thing was that my great-grandfather’s original text was full of mistakes and exaggerations. I wondered why that was over most of the four years I spent conducting the investigation. My final theory or conclusion is that, first of all, there weren’t any fact checkers at that time. He was a journalist, but he was writing something closer to a memoir than an article. Second, it was the year 1947. I can imagine that the period after World War II was a time of great drama in the collective of Jewish people around the world. So maybe exaggerating what had happened 50 years before was normal, or cathartic.

By exaggeration, I mean the way my great-grandfather describes the murders. In one, he writes that a girl had her eyes gouged out, her breasts cut off. But that wasn’t true. I read the sources from the time, which only reported a shot in the head. She probably was raped, which is really horrific, but her body was intact. So I wondered why he exaggerated in this way. And that was my theory, though it’s probably just a theory.

Tiffany Troy: Theories are interesting to me because I feel like even if the theories turned out to not be true, it’s about you working through the process of reading the newspaper. I was also interested in how you have so many different people speaking with you and sometimes you’re not sure if they are also exaggerating.

Javier Sinay: There was one person I interviewed who said that contradictions are not a problem, they enrich the story. They are like an advantage for the story.

Tiffany Troy: Robert, what draws you to Javier’s work?

Robert Croll: When I first encountered this book, I immediately liked the structure, the way it slips between first-person accounts of travel and recreated scenes of the past, balancing historical sources alongside modern interviews.

I also appreciate the fact that the book isn’t entirely conclusive. It accepts that there’s a limit to research, a limit to how much we can know about the past—Javier makes peace with that over the course of the book but still finds ideas along the way.

In part, the project appealed to me as a learning experience because it has such a different voice from any of the books I’ve translated before. There were practical lessons I could learn from the way Javier uses language. Of course, the multilingual elements also made the translation very difficult at times.

Javier Sinay: Yeah, yeah, you mean the Yiddish thing.

Robert Croll: I didn’t know how I was going to approach that initially, but I was looking forward to finding a way.

Javier Sinay: You know, in the original manuscript I had a lot more Yiddish, but the editor (Leila Guerriero), a writer who is very respected here, told me: “You have to cut down some Yiddish.”

Robert Croll: I liked the Yiddish.

Javier Sinay: How do you say exigente?

Robert Croll: It’s like “demanding.”

Javier Sinay: I think this is a very demanding book, you have to pay a lot of attention when you read. I was reading the English version and was like, Oh, I need to pay attention. I thank all of my readers, Tiffany, and Robert for reading this.

Tiffany Troy: And thank you for writing your book. Building off what Robert is saying, how did you structure your book?

Javier Sinay: It was really difficult to find the structure. First of all, I knew I had to use the chronology of the murders: from 1889 to 1906. Except, I think, for the penultimate chapter, which describes a crime from 1892, the others follow the timeline closely. Within each chapter, I wanted to talk about a specific facet of this very big cultural phenomenon.

The murder of Alberto Gerchunoff’s father, the one that happened in 1892, is the only crime that doesn’t follow the timeline. Alberto Gerchunoff was only a boy when his father was killed. By age 30, he was a very famous author here in Argentina, having published a book called Los Gauchos Judíos (The Jewish Gauchos) in 1910.

In that same year, there was a big celebration for Argentina’s centennial. But people from the ultra-nationalist far right came out to fight, light fires, and beat up Jews and immigrants. I wanted to talk about that time: in 1889 when the people of Moisés Ville came to Argentina, there were almost no Jews, but 20 years later, there was a reaction against the Jews because there were so many. I wanted to talk about that progression from nothing to a community to a pogrom, a riot against them.

So, in the chapter about the 1892 crime, I put in the 1910 riot. And in each of the others, I put in another subject to talk about. Each crime should be a springboard to talk about something else. I think about that in this and every book I write about crime, because they always feature something more.

For instance, my first book, Sangre Joven (a common expression in Spanish meaning “Young Blood”) is about the murders of young people committed by other young people. It’s young against young. These are people who were born in the 1980s. I was born in 1980, so apart from writing about crime, I wanted to make a portrait of my generation. The crimes provided an excuse to talk about my generation.

Robert Croll: It’s easy to dive into the violence and become sort of jaded, but I think you try to restore the horror of the violence and sometimes find a way to move beyond it.

Javier Sinay: I am fascinated by the violence. When I was younger, I said that violence should be useful to talk about something else, which is what I still say now. I confess, I enjoy writing a violent scene. But if you write only violent scenes, it’s a very monochromatic story. Good people, bad people, and a lot of blood. And it shouldn’t be that way. You have to think about the deeper cultural issues. People are not only good, not only bad: people are very complex. What is the crime trying to tell us about ourselves?

Tiffany Troy: Such a wonderful story about the Jewish gauchos. I was fascinated by your commentary, when you said that this is nothing like the actual story of the first Jewish people who came to the Moisés Ville, where the perception is entirely different and yet there’s this fictionalized, romanticized account.

Javier Sinay: The official version is very naïve and says that Jewish people and gauchos have always cooperated. But that cooperation started in the 1920s. Before then, there was a lot of friction and violence. Not just with the Jewish people but with all the immigrants—French, German, Swiss, Spanish—because the government of that time had the idea, though today we know it’s ridiculous, that European people could civilize the interior of Argentina, the provinces, which were then full of gauchos and indigenous people. So they pushed the indigenous people and gauchos farther and farther away or forced them to work on farms. Those who didn’t want to work as farmers were marginalized and became outlaws. I wanted to talk about the figure of the gaucho, which is very ambiguous and is also romanticized.

Robert Croll: Your interviews reveal widely differing ideas of what gauchos actually are or were.

Javier Sinay: I think we don’t know what gauchos are here in the cities of Argentina because they were people in the provinces. I don’t know if gauchos exist today. It’s kind of like cowboys in the United States—maybe some people would say there are still cowboys and some would say they don’t know. It’s become a commercial thing, maybe.

Tiffany Troy: Rob, how do you approach translating Javier’s work? We could start off with the voice. How are you able to carry the voices of the different characters so well in translation?

Robert Croll: You know, the voice is even slightly mysterious to me because it’s a quality that develops over time. My first drafts are always extremely rough, way too literal—there’s very little differentiation at that stage. The voices come out through revision and rereading as I start to understand each character’s idiolect over the course of the book. I definitely didn’t want to map people’s speech patterns onto regional dialects of English.

I also thought a lot about the use of Yiddish in the original. Naturally, the book uses a Spanish transliteration of Yiddish. I could have shifted everything into a more familiar English transliteration, and some words would have been easier to understand. But I actually wanted the reader in English to have to pause and come to the same linguistic realizations I did. The composition of the language itself tells you a lot about the history of immigration. I didn’t want to remove a middle layer and create a version that would read like an account of Jewish roots in the United States—I wanted to add an additional layer, so that the surface language itself would communicate the thematic displacement explored in the book.

Javier Sinay: I think it’s really cool what Rob has done, because the people from the provinces and from Moisés Ville speak differently than people from the cities. And the distance from Buenos Aires to New York is far but the cultural distance isn’t as far as that from Buenos Aires to Moisés Ville, which is only 600 hundred kilometers away, 12 hours by bus or coach or car, but life there is like 50 years in the past. There are good and bad things about that. They speak differently and are much more respectful with people.

Robert Croll: I like the connection between physical and temporal distance in the book. In a way, your journeys by train represent a motion through time.

Javier Sinay: You know, that posed a problem because I’m a journalist and this book was published in a narrative journalism collection. So it shouldn’t be a history book. At some point, I was sort of calculating what percentage I had in the past and what percentage I had in the present, and it was like 70% in the past 30% in the present. So, I said, I need 20% more stories in the present. I decided to travel to Moisés Ville one more time to ask the people more about their lives in the present day. Because, if not, it was going to be a history book and I didn’t want that. I’m not a historian, I’m a journalist.

Tiffany Troy: Javier, how do you approach interviewing the residents of Moisés Ville?

Javier Sinay: I had to go inside. One person who opened his door to me was “Ingue” Kanzepolsky. “Ingue” is a nickname that means “boy” in Yiddish, but he was over 80 years old. Not much of a boy. He was very curious about the people who came there from the outside because the town holds so much history for Argentine Jews. Now and then an investigator, historian, or journalist would come. There was a documentary film about Ingue. He was very happy to talk with me, and we spoke every day while I was there. I went to Moisés Ville four times, staying a week each visit, and was in contact with Ingue every time. He took me to La Salamanca, for example, a place I wouldn’t call dangerous, but which Ingue told me was Moisés Ville’s dangerous neighborhood. Not so dangerous if you’re from the city, but I thought that if I was going to write about violence in Moisés Ville, I needed experience its most dangerous part.

Ingue took me there and we spoke with a few people, like farmworkers, and I asked them about the gauchos. I asked one man who was around 70 years old if his father was a gaucho—he said, he was no gaucho. That’s because in the city we have a very naive, romanticized version of the gaucho. Out in the country, a gaucho is a bandit. It’s very different from the archetype of the gaucho.

Another person who opened her door to me was Eva Guelbert de Rosenthal, the director of the museum. She was the official voice of Moisés Ville’s history and knew a great deal. She was very curious about the crimes and knew about my great-grandfather’s text, but she’d never investigated it herself. So she was happy to help and gave me access to some old documents. She also told me about a few of the victims’ graves in the cemetery. That was a good starting point. From then on, I was out speaking with the people.

So I finished the book and felt like I’d covered the violence that has taken place in Moisés Ville. The last murder had been in 1973. I published the book in 2013, but then in 2015 there was a new crime. There were two neighbors who lived side by side, old enemies. One day one had an escopeta, how do you say that?

Robert Croll: A shotgun.

Javier Sinay: And he pulled the trigger, and the other guy fell dead. This was on a Thursday, and I thought, “Oh no, a new crime in Moisés Ville, I’ve got to be there.” I took a coach and traveled for 12 hours. I made it there on Saturday, and everyone in town knew about me. One of the two men was dead and the other was in jail. So I started asking people from the block about them. What were these people like? What was the problem? Did you see anything? There were family members, and it’s a very little town so they eat with the windows and doors wide open. They said, here he comes, here he is, he’s los crímenes. He’s “the crimes,” the murders. That was my nickname.

At this point if I go back, I can say hello to everyone in the streets and it will be okay.

Tiffany Troy is a critic, translator, and poet.