Reviewed by Kim Zach

Reviewed by Kim Zach

A Cartography of Home

by Hayden Saunier

Terrapin Books

February 15, 2021, Paperback, 98 pages, ISBN-13: 978-1947896352

A Cartography of Home is Hayden Saunier’s second full-length collection published by Terrapin Books. In these forty-eight poems, she explores the many manifestations of people and places we call home, whether metaphorical, literal, or natural. A quick scan of the contents reflects this theme, with titles like “Kitchen Table,” “Inhabitant,” “Advice Column: House Centipedes,” “Autumn Orchard,” “Unnamed Statue in an Unnamed Church,” “Standard Conditions on Earth,” and “Insomnia in a Highway Motel.”

The poem from which the collection takes its name, “A Cartography of Home,” employs the vocabulary of maps—compass, cardinal points, legends—as symbols of a mother’s guiding light. The poem begins, “My mother was a place. She was the where / from which I rose. Once on my feet, I touched / my forehead to her knee, then thigh, then hip/ waist, shoulder as I grew into my own wild country.” A mother provides security and protection, for the dangers of growing up are like “back roads, city streets, highway lanes that end / abruptly at the edge of broken cliffs” and the narrator imagines a long-ago map “where dragons snorting fire / ride curls of figured waves in unknown seas.” She ends with an homage to generations of mothers:

Before she died, I folded myself back

to pocket-size, my children tucked inside

like inset maps and I lay my head down on her lap.My mother stroked my hair

the way her mother had stroked hers,

and hers before hers, and on and on, and we

remained like that—not long—but long enoughto make an atlas of us, perfect bound,

while she was still a place and so was I.

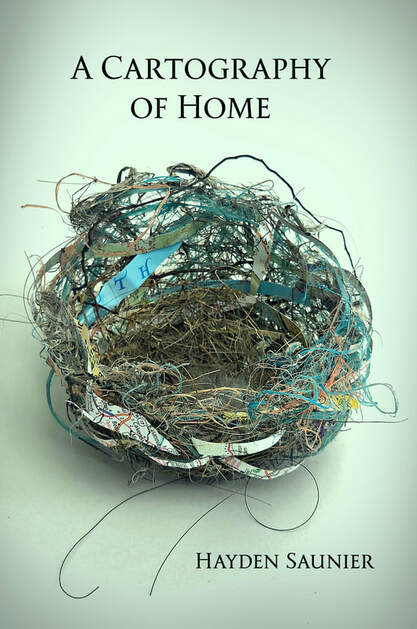

Several poems remind us that older houses often bear the marks of previous owners—some tangible, others less so. For example, in “Inhabitant,” the narrator relates her daily existence to theirs: “Whoever you were/you lived/in the rooms/ rinsed the cup, dried the plate/slept & wept & slept/the same three wooden steps.” This poem also inspired the cover art for the book—a bird’s nest, a universal symbol of home. She writes, “Today I lift / from the shaken-down scatter / an oriole’s intricate / basketry nest / blue twine woven through it / for structure.”

In “The Ones Who Built This House,” this time the narrator pays tribute to a human builder, rather than an avian one. The poem begins: “built it over years/with plumb line and level/room by room/hearth by hearth/stone by stone.” A carefully placed window affords a view of “east to west/so the pale sickle hook of a moon sliding/down the night sky/sets low in the frame/of the newest west window/and rises full butterfat cream/through the watery panes/of the old sash facing east.”

The opening poem “Kitchen Table” tells of repurposing materials while respecting their history. The poem feels rather timely considering today’s Modern Farmhouse trend, and the affinity for all things vintage, particularly wood and metal—the more worn and rustic, the better. It begins, “Our kitchen table’s made of walls. / Wide plans that sheathed clapboard, salvaged / from the sagging side of the house.” Just like in “Inhabitant,” the narrator acknowledges the history of that table: “Our table’s made of walls that held / a family of six before typhoid took / both parents and fostered out the children / to farm families needing help.” The poem ends with an invitation: “Our table’s wood / is spalted through with hard luck, grease, / disease, fat streaks of amber jam. / Our table’s made of all of it. / It’s us and ours. Sit down and eat.”

Saunier’s poetry abounds with visual and sensory details. They feel fresh rather than cliché, not an easy task in poetry. For example, in “Pantomime,” the moon is compared to “a fat apricot.” In “Deepening the Course,” she writes, “reflection makes mottled rocks / glow gray-gold as a mackerel sky.” A sunrise is personified in “Standard Conditions on Earth” as “this scarlet morning / explodes in argument with crimson, orange / fire-engine-red, which means I’m looking at the end / of the visible spectrum—its measured wavelengths / standardly interpreted as warning, danger, something / particulate ghosting the air we’re spinning through.”

Many lines are exquisitely crafted for sound and images related to nature. A reader might be compelled to read them aloud, for the sheer delight of hearing the alliteration, consonance,assonance, internal rhymes—all seemingly effortless. There are phrases like “liquid green-gold gathers” from “Liminal,” and phrases from “Forecast” like “Halfway through August, / summercracks / and shatters into thick clay shards / pieced quickly back together / with the sticky glue / of more hot days.” In “Autumn Orchard,” the images come in bursts of words like “yellow-gold /maroon with blush / and speckled rust,” “the seckel pear bows / bee-filled bells of sugar,” and “to the ground / where winter, soon / enough, will finger-comb / with cold.”

And finally, this stanza from “Navigational Notes” evokes a movie-like scene:

Paddle a slim canoe through a moonless night

beneath stars that rise and set

bright in salt water. Trail galaxies

of bioluminescent creatures

in your silent wake

until the curved bow of your boat

nudges a curved shore.

Saunier’s skills as a poet are showcased throughout this collection, but she works deftly and quietly, never browbeating the reader. A first read allows a simple pleasure in the words; it is upon a second and third read that nuanced layers unfold. For example, “Dirt Smart” begins with the lines, “You have to eat a peck of dirt / before you die, my grandma said. / I worried. Do I have to?” The poem continues with a description of the grandmother’s hard scrabble childhood in the tobacco fields “dug deep with labor, slaughter / and someone’s finger weighting every scale, / the way most land accumulation’s won.” At the end, she passes slice of wisdom: “She knew the dirt / you ate, the dirt beneath your fingernails, / dirt scrubbed from palm and kneecap / with cold water and a bristle brush— / that’s all the earth you own.”

These beautiful poems create a heightened awareness of how all things are connected. From the people who came before us, whether they built our physical house or built our family, to the natural world—dirt, sky, sun, moon, trees, coyotes, seasons, horses, fruit, flowers. It is all there for the taking; we have only to look for it.

“I’m Also the Fox” beautifully illustrates this interconnectedness. She writes:

Tonight, from the wood’s edge,

from the darkening rooms of my house, I’ll answer

the gaze of that fox with my gaze. She’ll turn backinto forest, I’ll step back into stone. Above us,

hickories and pin oaks will shoulder each other for sky.

About the reviewer: Kim Zach is a writer whose work has appeared in U.S. 1 Worksheets, Genesis, Clementine Poetry Journal, Clementine Unbound, Adanna Literary Journal, and Bone Bouquet. Her poem ‘Weeding My Garden’ was nominated for a Pushcart prize. She is a lifelong resident of the Midwest where she taught high school English and creative writing for 40 years. She currently works as a book coach, giving other writers the support and guidance they need to complete their projects, whether fiction, non-fiction, or poetry.