Reviewed by Morgan Bell

Reviewed by Morgan Bell

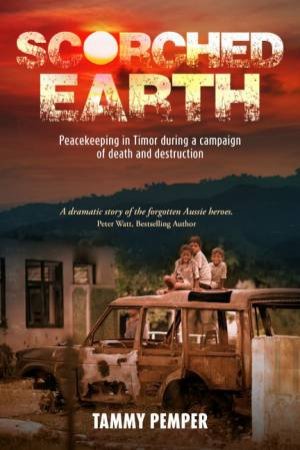

Scorched Earth

by Tammy Pemper

Big Sky Publishing

ISBN: 9781922265432, July 2019, Paperback, 320 pages

This novel takes places in East Timor over three weeks in 1999 during the time of their historic vote for independence. Tammy Pemper tells the story through the first-person voice of her peacekeeper narrator Peter Watt. Peter is a former cop. The first time Peter attempted to join the effort he failed his psych test due to being too honest. Peter is sarcastic in his own thoughts, and sometimes in quips. We see him develop from someone always trying to boil life down to basic elements, to someone humbled by the things he has seen.

Pemper uses her first chapters to introduce a love interest for Peter. She is a blonde woman named Shayhara. She is working abroad in England for the duration of Peter’s assignment. Peter yearns to hear Shayhara’s voice but doesn’t know how she feels about him. Later in the novel, at a time of anarchy, Shayhara is the one Peter phones and talks to. This intriguing sub-plot that adds dimension to Peter.

The story opens with the premise that it’s impossible for peacekeepers to stay neutral. Peter meets his UN supervisor Gerhardt – a pale Austrian in his dark blue cargo pants and a light blue shirt (the UN peacekeeper uniform) – in the heavily militarised East Timor airport. From Gerhardt we learn about the Aitarak militia in Dili. We also learn about a recent incident of sixty dead in Liquiҫá church. The victims were shot, hacked with machetes, tear-gassed and executed. Gerhardt tells us early: “We’re not mandated to protect Timorese even if they’re attacked at our feet.” The role of the peacekeeper here is solely to observe and report to local forces. Those local forces are the Indonesian-controlled police. The Indonesians are invested in keeping East Timor in an occupied state.

As Gerhardt drives Peter from the airport to the base, Peter observes the locals. Women balancing banana-leaf baskets on their heads, infants slung across their chests. Men scaling palm trees, machete blade between their teeth, to cut down coconuts to sell and eat. Peter is struck by the normalcy of serene village life. The sweeping brooms. The laughter. The children’s games. A militia encampment in plain view on the main street is described as crudely assembled bungalows built on rocky soil. The UN base is perfumed with spiced incense cigarettes.

The vivid description of the landscape captures the stillness and contentment of the milieu. However, some aspect of the terrain is always disturbingly askew. Pemper has an impressive command of language, a necessary skill for creating a sense of place in what could easily be a generic theatre of war. In a perfect analogy for the social upheaval, the wheels of Peter’s truck are seen brushing the edge of the abyss at a cliffs edge during the journey. The remnants of a destructive landslide hinder the way forward on the road they travel. Woven into the background details is this lingering sense of danger and disturbance. It feels precarious.

Take this passage about a typical beachside hut with its merchandise on display: “The goods ranged from short timber planks stacked crisscross a couple of metres high, to a dozen little fish hanging as a bundle from the end of a bamboo pole stabbed into the ground, to dry leaves woven into sheets the dimensions of a fence panel. The sheets rested on top of roughly-hewn tables under which abscessed dogs with exposed ribcages lay panting.”

It is placed next to a scene where red and brown splatter can be seen on a sea-wall ledge. Trawling around are some surprisingly well-fed dogs. Peter is asked to imagine “whose bodies are feeding them.” Pemper uses a cinematic technique of panning the camera around and letting the observer discover the patterns and what’s out of place. We see more than guns and bloodshed. We see a panorama of the quiet everyday before being pierced once more by military aggression. We see beyond what is there. We see what is lost, and what is at stake.

Details of crimes are littered throughout the novel, often in casual conversation with not much reaction from the peacekeepers. The violent reality of life in Timor is simply the soup they swim in. Peter hears a rumour that fellow Timorese have taken to poisoning each other at dinner parties with traditional jungle mixtures of bark, stems, roots, and sap. A Spaniard peacekeeper, Nazario, confides in Peter that he suspects the husband of their local host, Filomena, may have been killed as retribution for her renting the house to UN workers.

Conflict breaks out a quarter of the way into the book with the arrival of Elvis Jeka at a polling place. The “Clank. Clank. Clank.” of militiamen’s machetes on the sides of their trucks rises to a crescendo. Gunshots ring out and bullets tear through the mass of bodies lined up at the polls to vote. The fast-pacing continues with the “Crack. Crack. Crack” of a revolver and the “Go! Go! Go!” of Nazario’s calls to flee. Peter discovers the crimson slashes of an execution wall and giant red letters graffitied saying “UN GO HOME”. There is a mayhem of smoke and reversing vehicles and radio comms.

The novel contains a respectable amount of technical detail. Pemper names all the various factions and splinter groups and military units, for all those war-history wonks out there. But more than that, the events have been crafted into the narrative arc of a pleasingly familiar three-act structure. Peter changes because he is affected by the events. We care about his journey. It is not like reading an officer’s log or a collection of newspaper clips. Despite half the chapter having headings that are dates, this doesn’t feel at all like journal entries. There’s a little bit of repetition of phrases, but given that the details are patchworked together from multiple accounts, Pemper was wise to err on the side of continuity.

Scorched Earth is a largely apolitical work with an unabashed narrow scope. The focus is on the peacekeepers and the vote only. The novel did pay some reference to the role of the American and Australian governments training and selling arms to the Indonesian forces. But there is not much context given on the decades of conflict and occupation that led up to these two weeks in 1999.

At one point, Peter is told that he resembles the leader of the Timorese resistance. The man who utters that statement is a lighter-skinned local. Peter identifies as potentially mixed-race, and speculates that maybe a descendent of the mutiny on the Bounty. A simple passage like this is a clever inclusion. It serves to illustrate the historic bond between Australians and Timorese. A kinship in the quiet moments. We are cordial neighbours. But we are also loosely-related mates.

All profits from the book go to Timor. The story is based on personal experience and the memories of personal contacts. A Timorese survivor, Celio Alves, has his story included in the book and writes in his testimonial that a political prisoner once said, “if you don’t tell your story, then who will?”

About the reviewer: Morgan Bell is a Port Stephens author of short fiction. Her books include Sniggerless Boundulations, Laissez Faire, and Intersection Control: Collected Works. She is a qualified technical writer, creative writing teacher, and editor of Sproutlings: A Compendium of Little Fictions. Her chapbook of concrete poetry is Idiomatic, For The People.