Reviewed by Carole Mertz

Reviewed by Carole Mertz

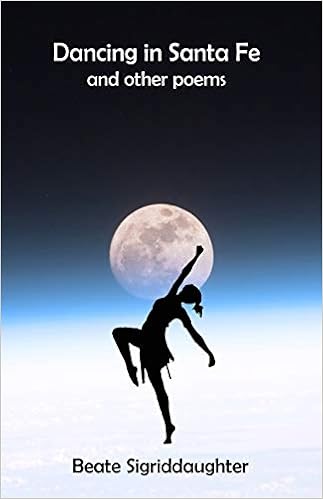

Dancing in Santa Fe

and other poems

by Beate Sigriddaughter

Cervena Barva Press

ISBN: 9781950063239, Sept 2019, 24 pg, Paperback, $8.00

In Dancing in Santa Fe, Sigriddaughter delivers a fine collection of fourteen poems written in free verse. An American poet of German heritage, she has won many poetry prizes, including the Cultural Weekly—Jack Grapes Prize in 2014, and multiple nominations for the Pushcart Prize. Her gracious promotion of women’s poetry (at her blog Writing in a Woman’s Voice) is commendable.

Richness of character and content run throughout the collection. These represents the author’s wealth of resources and display her thoughtfulness resulting from inward reflection, along with her ability to define external scenes surrounding her.

In “Lines for a Princess” (21), the persona is at once a sheltered flower, a mountain juniper, a “seed that never quite took,” and a poet who “wants sequins and justice both.” I like the depth of this persona’s character and appreciate the clarity with which the narration is rendered. In it Sigriddaughter writes, “Days whisper by. You have to / listen carefully to hear them.” The poem is one among others in the collection that draws on fairytale themes

A longer poem, “Dancing in Santa Fe” (4-7), gives alternating verse backdrops of such weighted matters as concentration camps and war’s horrors, contrasted with New Mexico’s beautiful mountain scenes. “…to feel for sins I haven’t committed?” she writes, as autobiography. “…is an unspeakable filter / on this gorgeous world.”

The poems, “Samsara” and “Nirvana” draw on Buddhist religious terms to deliver their messages. As wanderer, in “Samsara” (8-9), the poet writes:

Even on the mountain, surrounded

by excellence, the trouble

of the city clamors in my heart…

In “Nirvana’ (p. 10), Sigriddaughter issues a plea:

I love you world. Send more angels.

Help me fight the dull and dangerous

deceptions.

Here she admits her distrust of “nirvana,” a striving after bliss and the absence of suffering or desire. (Isn’t self-effacing consent like suicide? she asks.)

“The River” (11) brings to the reader another level of reflection; the river acknowledges being bound to desires. Accepting this, it wants to carve passageways through mountains of unnecessary evil. I enjoy the beauty of this metaphor and how it allows the river to speak Sigriddaughter’s own spiritual desires.

In addition to her narrative skills, the poet’s mature voice also lends beauty to her verses. We trust her voice all the more, because it doesn’t conceal the imperfections of the world. “I have heard,” she says in Scheherazade (16), “how not forgiving is like drinking poison.” And with further insight, “You cannot be my hero any more…I cannot imagine the cost / of making nice with the entitled predator / like that.” A subsequent line strikes an even stronger point.

Though several poems lead us to reflect on beauty and dark matters, such as war and unforgiveness, Sigriddaughter chooses to close the chapbook with a humorous poem. In “The Dragon’s Tale” (23), the princess is hidden away from “benevolent contempt.” We content ourselves with this comedy when the dragon asks, “You thought I was going to eat her?”

I delight in Dancing in Santa Fe. Its content seems to “fill the narrow margins of reality with beauty.” (15) Beate Sigriddaughter’s poems balance darkness with a joyful light.

About the reviewer: Carole Mertz, poet and essayist, has reviewed for World Literature Today, Cutbank, Into the Void Magazine, Eclectica, Mom Egg Review, and elsewhere. She is book review editor at Dreamer’s Creative Writing. She is the author of Toward a Peeping Sunrise (Prolific Press, 2019).