Reviewed by Ruth Latta

Reviewed by Ruth Latta

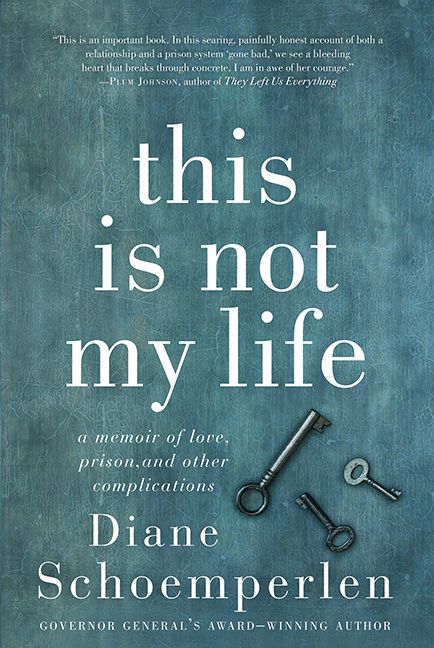

This is Not my Life

Harper Collins

2016, ISBN 978-1-44343-420-1, April 2016, 368 pages

Diane Schoemperlen’s memoir of love, prison, and other complications, has a terrific opening sentence which I long to quote but will let readers discover for themselves. This is Not my Life is about the well-known Canadian author’s six year relationship with “Shane” (not his real name), convicted in the early 1980s of second-degree murder. They met at a food program run by the St. Vincent de Paul Society in Kingston, Ontario, a city which had eight federal penitentiaries within its limits or in the surrounding area.

Schoemperlen, then in her early fifties, had been writing and publishing books for twenty years, and had won the Governor General’s Award for one of them. A successful writer, a homeowner, and the single mother of a son in his early twenties, she volunteered in the “Vinnie’s” food program on the advice of a friend, who thought it would help her get over a failed relationship and writer’s block.

Shane, a prisoner in his late fifties, volunteered as a dishwasher, on an Escorted Temporary Absence from the Frontenac Institution. After spending nearly half his adult life behind bars, he was hoping to get day parole and move to a halfway house. He and Diane felt an immediate attraction to each other, and when the nun escorting him to and from prison could no longer serve, Diane applied to escort him. On their drives, and at Vinnie’s, they got to know each other. Realizing that she had fallen in love with Shane, Diane recognized that making a commitment to him was bound to be “complicated and life changing.” Their six year relationship was indeed that.

Loneliness, aging and being on the rebound may have played a part in her falling in love with him but the main factor, in her view, is that she always liked “bad boys” and that she had “class issues.” From a working class background in which her academic and writing talents were not valued, she felt akin to Shane, whose origins were even more fraught than hers. Although Schoemperlen does not says so, human kindness and altruism also played a part in drawing her to him.

Sadly, the memoir seems to prove the old adage: “No good deed goes unpunished. When Shane was released back into society, Diane welcomed him into her home. While she acted out of love and longing for a partner, it is obvious that she was doing him a tremendous favour by providing a home for him. Rather than appreciating this haven, Shane criticized her housekeeping and overflowed with plans for renovations and purchases, not caring that, domestically, her life had been working well.

Although their relationship eventually collapsed under its own weight, a “trifecta of bureaucracies seemed to be setting [them] up to fail.” All that Correction Services Canada offered inmates returning to society was a “list of free food agencies and a visit to the welfare office.” Ontario Works told them, belatedly, that if Diane had declared herself Shane’s landlady, he would have been eligible for start-up money and the full monthly welfare cheque for a single person. Since he had her home to go to, he was ineligible for these supports. She was also angry at the Parole Board for giving Shane to her “with the tacit understanding that [she] would look after him, without explaining that he would be penalized for that. Money was always a problem, given Shane’s urge to spend.

Another issue was the time she needed to write. This aspect of the story shows the disrespect that writers constantly face from society. Although Shane claimed to be a book lover, and although he enjoyed coming with her to literary events, he did not realize how much uninterrupted thought goes into writing a novel. When he was in prison or in a halfway house he interrupted her with constant phone calls, and tried to force her into a scheduled writing time, apparently unaware that a writer’s mind is always working. Their counsellor, a psychologist from Corrections, leaned toward Shane’s view that she should limit her hours to write.

“It’s awfully late in the game for me to be fighting for time to write,” she told them. “I’m sure if I worked in an office, if I were a teacher or a doctor or even a sales clerk, Shane wouldn’t think it was okay to call me all the time when I was at work.” When she tried to reduce her writing to the level of dollars and cents, Shane felt accused of not contributing to the household. The psychologist’s remark, “I don’t read much but my wife does”, so oft-heard that it is a cliche, and Shane’s suggestion that she “find another line of work” show a shocking disrespect toward an award-winning author and toward the creative arts in general, (though Schoemperlen does not say this.)

One incident in particular stood out as symbolic. When Shane was helping Diane garden, he offered to pull out the “weeds” growing along her walk. Diane explained that they were not weeds, but flowers, “bleeding hearts” and he desisted. Metaphorically, however, Shane ripped out Diane’s bleeding heart. A “bleeding heart” is a sympathizer with the underdog, someone who tries to right social injustice. Growing up as something of an underdog herself, Diane was a bleeding heart for a long time with regard to Shane. Now, although still a sensitive and humane person, she realizes that love does not conquer all and that there is only so much one can do for a needy person without ruining one’s own life.

It was Diane’s profession, so hampered by Shane, that rescued her. At a writers’ conference, hearing a famous author present a story and then the reality from which it was drawn, she realized that she had been telling herself a story that prevented her seeing the reality of her situation with Shane. “The story was so beautiful, tender and romantic. But… the reality was only abusive, destructive and unbearable.”

This is Not my Life will strike a chord with anyone who has been dragged down by another person’s needs. Many of us know people who lurch from one catastrophe to another and who manage to screw up whenever they catch a break. Over the years, I have closed the door on several people when they took too great a toll on me and infected my life with despair. As a left-wing person raised to practise the Golden Rule, I have felt guilty about it, since, on at least one significant occasion, my life was transformed by someone who took a chance on me. The question of when to open one’s heart and when to close it is an ongoing one. Diane Schoemperlen’s experience with Shane casts light on this question and makes us feel less alone in the struggle. Her wry humour and way with words keep it from being maudlin.

Ruth Latta is a writer in Ottawa, Canada. For more information about her books, visit http://ruthlattabooks.blogspot.com