Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

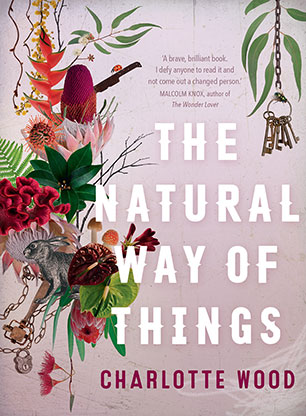

The Natural Way of Things

By Charlotte Woods

Allen and Unwin

ISBN: 9781760111236, Oct 2015, 320 pages, paperback

I’ve had The Natural Way of Things on my bookshelf for months, and I’m sorry I left it so long. Since I received it last September, the book won three major awards including this year’s Stella Prize, and shortlisted for a whole bunch of others, including the Miles Franklin. It’s easy to see why. The book is stunning—a virtuosity of writing and storytelling that is at once enlightening and deeply chilling. The story immediately places the reader into a situation of cognitive dissonance that never dissipates. Nineteen year old Yolanda Kovacs awakes in the dark to the sounds of birds, and realizes she is imprisoned, her handbag, clothing and other things gone. After another girl, Verla, is ushered in, the girls both have their heads shaved with a brutality that might fit in a concentration camp. They are then dressed in old fashioned, Amish style clothing and put into a room with eight other women who have been drugged, shorn, and ultimately chained together behind an electric wire fence. As they are marched to the cages they’ll be living in, the girls are brutally mistreated, both verbally and physically.

The story of the girls’ imprisonment unfolds slowly, with a controlled series of revelations that keeps the reader in as much darkness as the protagonists. Revelation takes place in small illuminations amidst the pain, torment, work, betrayals, and emotional adjustments to the nightmarish reality. The desire to uncover the truth about what has happened, and ease some of the tension pushes the story along very quickly, using a dreamlike logic that allows for poetic concatenation:

Then a determined, rhythmic crashing starts up through the trees, through the viney cloth draped all about her like torn circus tents. Her horse! But even before she turns she knows it is not her horse but Boncer. She is caught; It was always coming. She turns as in a dream for him to shoot her, rape her, bludgeon her. (135)

Sexism might be the elephant in the room, never named but permeating the scene. In this dystopian fable, toxic masculinity has gone so far to its conclusions, that it becomes the antagonist. The brutal misogyny at play here is far more pervasive than the repeated beatings given by Boncer, the most violent of the two unpleasant gaolers. Though Boncer is a hateful character, he is no more in control than the girls are. He is as much trapped by the ‘natural way of things’, typified by the electrified fence, the control exerted by the “company,” and their allotted roles, as the girls are:

Then she saw Boner’s white-knuckled hold on the leash strap. Saw his skinny pale mosquito-bitten wrists. She saw, finally, what Boncer was: a stupid ugly child, underfed, afraid. He saw his pocked old acne scars.

Pity fought fear. (142)

The corporate behemoth behind the imprisonment, “Hardings International”, becomes emblematic of society itself – those things we sanction in the name of what is and isn’t natural. I italicise the word natural because the word takes on a myriad of meanings in this book, some hinting at societal norms, and others implying a deeper kind of natural–the bush, the animals, our underlying selves. There are plenty of moments in this book when it would be easier to look away: the violence of Boncer’s whip or the numerous deaths and disintegration of the characters, but the most disturbing is the the intensity of the girl’s desire for high-end beauty products, typified by the Phaedra giveaway bags. This is the point at which the book truly shifts away from a dystopia ‘what if’ exploring a scenario taken to its extreme end, to a searing insight into a modern day imprisonment we’re all implicit in. The matrix is revealed:

And she stood in the street before the Louboutin window, that vertical slipper with its red needle heel poised in the glass dome like a jewel, a test tube, a syringe. Like a pharmaceutical thing to enhance you, heal you, cure you. (304)

Even at its most horrific, the writing remains exquisite, every word doing its part in this masterful book. The symbols and metaphors are rich, but subtle, inherent in the narrative. The setting is desolate, and yet there is beauty to be found throughout:

The river is a wide rope of bronze silk twirling, and Verla hammocked inside it. She is a creature of the animals, of kangaroo and horse; she is a little brown trout very still in the water, then a twitch and it’s away, somewhere in that channel, scooped along by the river’s strong brown hand. (138)

The character arc for both Yolanda and Verla is dramatic, and fully believable. There is something all too familiar in their stories, in the way they were treated in the media, and in how they are hushed, debased, and punished. It’s a story that we see repeatedly in the headlines. There is something even more familiar in the way that the girls both bond with, and hurt, one another and especially in the way they respond to the tiny gifts designed to pacify them, whether that be approval from the gaolers, or silver razors. This may look like a dystopia but it’s a devastating critique on the standard we’ve come, as a society, to accept.

The Natural Way of Things is an easy book to read but a hard one to digest. It holds up a mirror that shows an ugly reflection of the relationship between capitalism and misogyny that once glimpsed cannot be unseen. Though it’s disturbing, The Natural Way of Things is also powerful, beautiful, and utterly important.