By Daniel Garrett

By Daniel Garrett

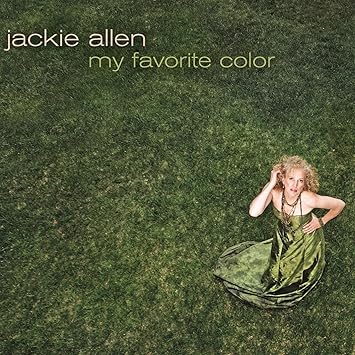

Jackie Allen, My Favorite Color (Avant Bass, 2014)

Heather Pierson, Motherless Child (Vessel Recordings, 2014)

Jackie Allen has a light, sensuous, pretty voice—and that is a very good thing: her voice has personality, and is given to sensitive expression on her album My Favorite Color, a good and varied collection of songs. Consequently, Jackie Allen’s handling of a song such as Arlen and Capote’s “A Sleepin’ Bee,” about a test of love, is lively and sweet. “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy,” a song by Joe Zawinul, written for Cannonball Adderley, to which the Buckinghams added lyrics, is entertaining and slinky. Jackie Allen’s seemingly light voice has a low, rumbling bottom—and her interpretations seem singular, as with “My Man’s Gone Now,” which is supported by Steve Eisen’s (strange, haunting) saxophone playing—the whole arrangement has a unique quality, beautifully bruised, troubled, tumultuous. The care and control, the varieties of tenderness, create surprise and pleasure in “Blame It on My Youth” and other songs. Of the song “Blame It on My Youth,” USA Today critic Elysa Gardner said, “Allen gives the standard a relaxed but haunted vibe—and a lovely acoustic guitar intro, via John Moulder” (May 20, 2014).

The Wisconsin-born Jackie Allen, a songwriter and educator as well as singer, has made a lot of music, live and recorded: some of her recordings are Never Let Me Go(1994), Which (1999), Landscapes – Bass Meets Voice (1999), Santa Baby (2000), Autumn Leaves (2001), The Men in My Life (2003), Love Is Blue (2004), Tangled (2006), and Starry Night (2009). Jackie Allen has toured Asia and Europe and parts of North Africa and South America. “The voice—dusky, mellow and wise—is as spellbinding as ever, now shot through with a captivating world-weariness, her folk-rock roots clearly showing,” wrote Christopher Loudon when describing My Favorite Color for JazzTimes (June 15, 2014), calling “exquisite” Allen’s own compositions “Diana” and “Call Me Winter.”

On Jackie Allen’s My Favorite Color, the subject and the spoken and sung aspects of Jimi Hendrix’s song “Manic Depression,” as well as its instrumental music, bring a sense of experience and experiment. Allen gives a sense of pique to “Stuck in the Middle with You,” which began as a satire (and tribute) to Bob Dylan and has here a busy, shiny arrangement. Then comes “A House is Not a Home,” “Diana,” “Born to be Blue,” and “Call Me Winter.” Repertoire is very important for a singer—it exemplifies intelligence, sensitivity, and taste, but more than that, it defines the range of things a singer can say.

A healthy, stable life is messed up by love—and “I know how those junkies feel” the narrator sings—in “Junkies,” the song with a blues piano rhythm that opens Motherless Child, the album by singer Heather Pierson, a woman with a formidable voice—large, rich, forceful. However, there is not enough of a described relationship in “The Gumbo’s Too Hot”—and “you cooked it too long”—to know if the lyrics are more metaphorical than practical, although it is an amusing subject for a song, especially for American southerners. Singer, guitarist, and pianist Heather Pierson, whose work draws on folk, jazz, American popular standards, and rock music, has to her name the recordings Wrestling Angels (1996), Onward & Upward (1998), Honor the Light(2000), We All Have A Song (2001), Between Lives (2003), Make It Mine (2010), The Open Road (2012), The Hard Work of Living (2013), and now Motherless Child(2014). Kansas-born daughter of a Scottish mother and American (Missouri) father, a father who would teach his daughter how to play piano, Heather Pierson lived with her family from age five in Maine, a family of pain as well as pleasure—there was tragedy there, including the early death of both parents. Pierson has performed with a country band and women’s vocal group, and her and musical experiences seem to have given her a mature vision—for that is what she brings to her selection of songs, which include on Motherless Child such compositions as “Norwegian Wood” and “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out” and “When You Wish Upon a Star.”

Expressive, forceful, and honest, “Dirty No-Gooder’s Blues” assumes a classic blues perspective about a no-good man (it’s a Bessie Smith song): “The meanest thing he could say / would thrill you through and through / and there was nothing too dirty / for that man to do.” A strange song, “I Loves You, Porgy” is an avowal of love that is at the same time a confession of conflicts, of desires that can be aroused by a different, less trustworthy lover, may be too healthily performed. “Ain’t Misbehavin’” is pretty, even sweet. “Motherless Child” works more as eloquent public speech than as an intimate personal statement. I do wonder what Pierson might do with a more idiosyncratic batch of songs.

Purchasing links:

http://www.cdbaby.com/cd/jackieallen

http://www.cdbaby.com/cd/heatherpierson4

Daniel Garrett has written about art, books, business, film, and politics, and his work has appeared in The African, American Book Review, Art & Antiques, The Audubon Activist, Cinetext, Film International, Offscreen, Rain Taxi, The Review of Contemporary Fiction, and World Literature Today, as well as The Compulsive Reader. Author contact: dgarrett31@hotmail.com or d.garrett.writer@gmail.com